Where the building you need for your plot doesn’t exist, build it yourself, says author Nick Jones.

For nearly 20 years I lived in central London, working as an architectural journalist. Buildings, you might say, are in my DNA (though I have to confess I feel no great affinity for the capital’s showy 21st century monoliths, such as The Shard or the Walkie-Talkie).

My latest novel is a psychological thriller set in rural Shropshire. It features some fine old buildings, many of them architectural gems, such as the 17th century black-and-white coaching inn in Ludlow, The Feathers Hotel. This small market town has been described by no less an authority than Sir John Betjeman as ‘probably the loveliest town in England.’ Last summer, I haunted its quaint narrow back streets to get the right atmosphere for the novel. Basic ground work like this – rather than internet research – invariably pays off. I am always armed with a camera and a notebook.

The latter stages of my story involve a murder trial in Shrewsbury Crown Court. I sought – and obtained – the presiding circuit judge’s permission to sit in on a trial and take notes (something members of the public are not normally permitted to do in crown courts). I had to give the judge an undertaking that neither he, the defendant, the lawyers nor any members of the jury would be identified in the book.

The defendant in my fictitious trial is the novel’s main character, book shop owner Anthony Metcalf, the victim of a predatory female stalker. In the case of murder charges, the accused is seldom bailed. So with hearings lasting more than one day, the defendant has to be transported to the nearest remand prison for overnight stays. Living conditions in remand prisons vary enormously, as a recent Home Office report revealed. By far and away the most notorious English prison was Shrewsbury’s Dana Gaol. It was once the second most crowded prison in England, with the highest suicide rate. Thankfully, it is now closed and scheduled for redevelopment.

But with The Dana gone, where was I to house Anthony Metcalf overnight?

The setting had to sound authentic and I needed him to interact with some ‘old lags’, who could bolster his flagging morale, as the Crown Prosecution Service’s case against him looked pretty formidable. One of his fellow inmates (my favourite character in the book) is wily old West Indian accountant Herbert Carter, on remand for embezzling over £1/2-million from his clients’ accounts. The bookish Herbert can even recite lines from A E Housman’s A Shropshire Lad.

I decided that the simplest solution (circumventing the bureaucratic red tape of authorisations required to visit a real prison) was to build my own!

Thus HMP Carding, set in lush Shropshire landscape near Craven Arms, came into being. As I explain to readers, it was originally a Victorian TB sanatorium before being converted by the Prison Service.

It has a central exercise yard, around which the prisoners have to walk every Sunday morning, in the manner of the famous Newgate Gaol etching by Gustave Doré. The yard is dominated by a gaunt clock tower, with the hour and minute hands removed from its clock face, as if to remind inmates that inside HMP Carding, time stands still! On a wall beside the entrance to the prison’s chapel, I decided to ‘erect’ a marble plaque dedicated to the sanatorium’s benefactor. I found (and copied in every detail) such a memorial, from the interior of the church of St George’s, Bloomsbury, one of the most beautiful Hawksmoor churches in central London.

The jewel in the crown of my imaginary Shropshire prison is this chapel. Here, I confess, I pulled all the stops out, reasoning that a Victorian hospital specialising in the care of terminal consumption cases, might well have included an impressive place of worship for patients and their families. The ceiling is lined with gilded scallop shells and its mahogany pews have crimson velvet seats and kneelers. The chapel’s two stained glass side windows show the figures of saints connected with healing, while in a dish-shaped alcove above the altar, is a gilded mosaic depicting St Raphael the Archangel, the principal ‘healing saint’. To add a sombre and reverential atmosphere, I bathed the whole interior with deep ruby candelight from a high-level, cut-glass sanctuary lamp.

So I would suggest that – with buildings at least – where a known example doesn’t precisely fit the bill required by your narrative, then make it up. Building castles in the air can be extremely rewarding.

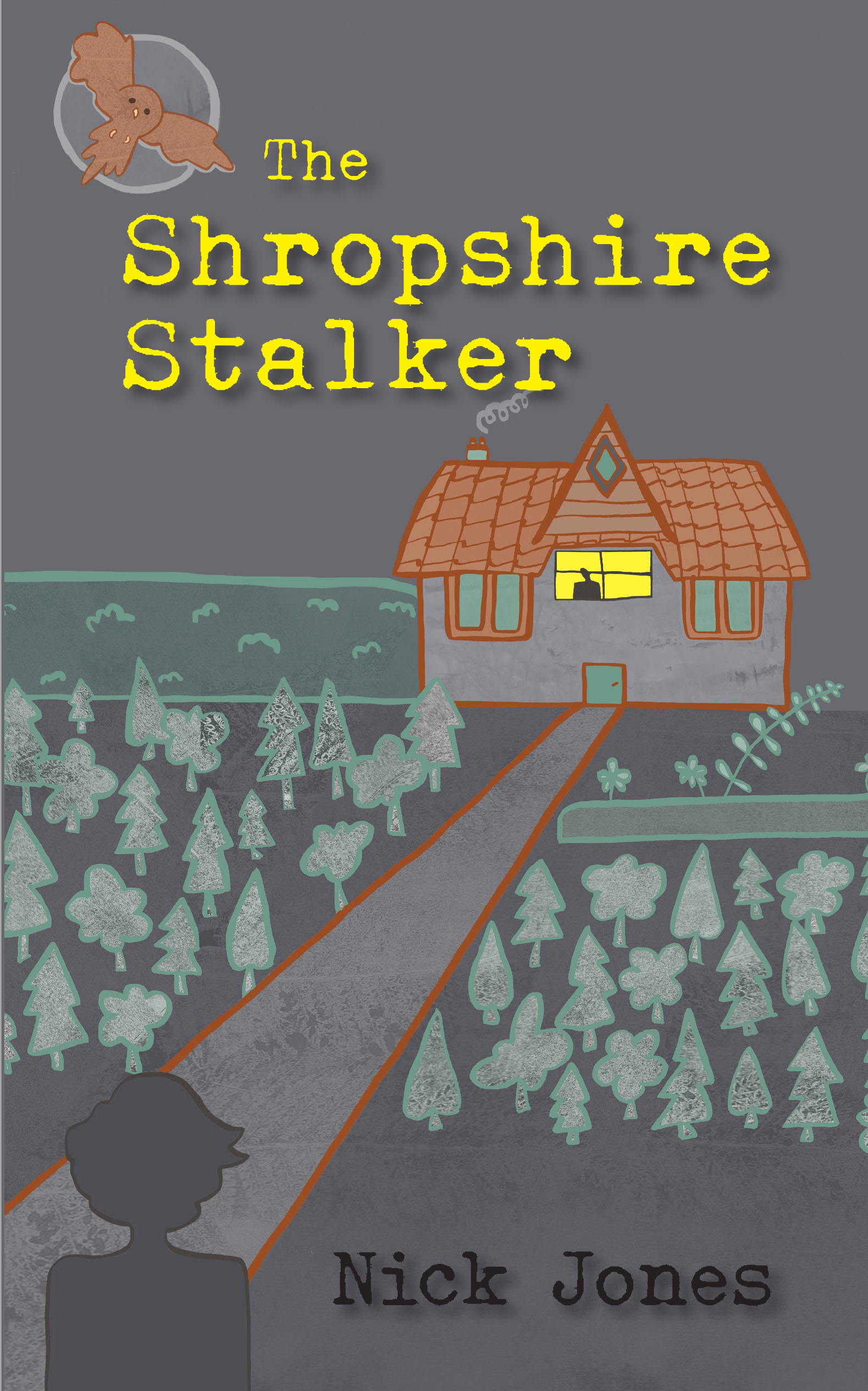

Formerly an architectural journalist and feature writer, Nick Jones now lives in Herefordshire. His debut novel, ‘King’s Cross’ (genre: supernatural), was published by Book Guild Publishing in August 2015. His latest novel – a psychological thriller entitled ‘The Shropshire Stalker’ – will be published by YouCaxton Publications on 1st August. Nick can be contacted at www.ampersandworld.co.uk

Thanks for the tips ☝🙏

What a beautiful book cover, colleague!

As I live just over the border in Powys and know places such as Ludlow and The Feathers very well I must read this one!