Sally O'Reilly looks at the practicalities of being able to carve out enough time to take your novel forward.

Before you send your work anywhere, it needs to be as good as possible – original and exciting as well as beautifully presented. Making your work excellent takes practice – a lot of practice. It might be tempting to imagine that you can write a novel in a year, or even a month as many people do during NaNoWriMo in November. But even if you do ultimately write some books more quickly than others, all writers need to learn their craft over time, and develop confidence and fluency. In that sense there are no short cuts to writing brilliant fiction.

Now for the good news. The fact that writing takes practice suggests that writing talent is not about being a special elite person in possession of untrammelled genius, and that only the chosen few can write books of any value. Quite the reverse. A lot of manuscripts which languish on the slush pile in literary agencies are produced by writers who mistakenly think that they can dash off a novel when the mood takes them, and that their innate writing flair will translate into winning the Booker with their first attempt. First novels do win prizes, but writers who succeed are invariably those who have written a great deal, in some capacity or other. Malcolm Gladwell, author of Outliers has suggested that in order to excel at anything, we have to put in a certain number of hours of practice.

Gladwell’s theory is that all great artists have practiced their art for at least 10,000 hours. While he accepts that talent is unevenly distributed across the population, he points out that those who excel are those who work the hardest. He cites the work of the American neuroscientist Daniel Letivin, whose wrote the international best seller This is Your Brain on Music: Understanding a Human Obsession. Letivin writes that ‘in study after study, of composers, basketball players, fiction writers, ice skaters, concert pianists, chess players, master criminals and what have you, this number comes up again and again.’

One example is the Beatles, who seemed like a bunch of effortlessly natural entertainers when they stormed to success in Britain and America in the early sixties. Their talent was of course extraordinary, but the Fab Four weren’t artless ingénues. Between 1960 and 1962, they made five trips to Hamburg, where they played seven days a week, often for eight hours at a stretch. Gladwell writes: ‘All told, they performed for 270 nights in just over a year and a half. By the time they had their first burst of success...they had performed twelve hundred times.’ Most bands, Gladwell points out, don’t perform together that often in their entire careers.

You may not have the opportunity to immerse yourself in writing in quite such a dramatic way, but you should take any opportunity you can to write and practice different approaches. Some writers, like Julia Cameron, suggest writing morning pages every day. Set your alarm for an hour earlier, get writing and you will have started the day by honing your skill. Don’t assume that only ‘creative’ writing counts – I learned my craft as a freelance journalist, writing about careers, children and city finance. I know how to write to length, cut to the chase, the importance of specific detail and concrete facts. Press releases, publicity material, even company reports all have their place. Set yourself targets – a short story a month, a chapter of your novel every two weeks and so on. And read widely, eclectically and all the time. If you jot down your impressions of every novel that you read, and try and analyse its successes and failings, you will build up an invaluable resource that you can draw on – and you will be writing about writing. All of this goes towards your 10,000 hours.

Personally, I don’t believe that there is a magic number that guarantees excellence, but I do believe that writers write. And I have put in 10,000 hours myself. It’s vital to prioritize: I avoid TV and ironing, and my house is cleaned only on a need-to-dust basis. But I read and write all the time – on train journeys, in cafes, on park benches. Every film I see gets a note, every book I read gets a paragraph. Working as a creative writing lecturer helps, because everything I do relates to writing in some way. But I have operated like this since I first had children, and every second was precious. Unlike hoovering and doing the accounts, writing feeds my energy, and the more I do, the more inspired I feel.

The beauty of the 10,000 hours philosophy is that every word you write has value, adding to your confidence and knowledge. There is no such thing as a wasted draft, or a paragraph that you shouldn’t have written. As long as you are keeping the words flowing, you are learning. And as long as you are learning, you are getting closer to being as good as you can be. You may not win the Booker, but you will have developed a writing practice that has transformed life into Art. And who knows where that will lead?

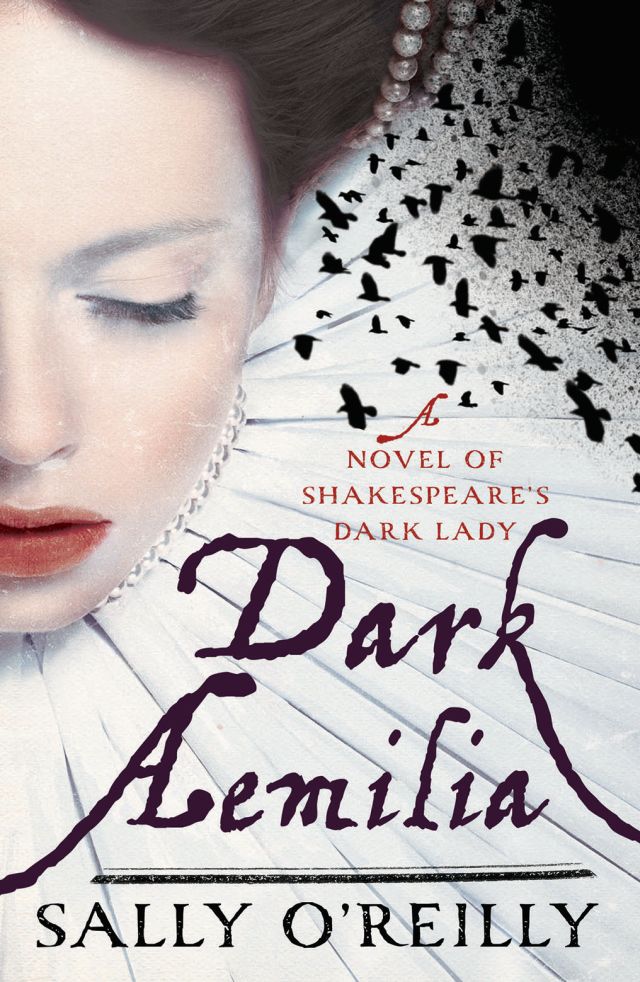

Sally is the author of two contemporary novels published by Penguin books and her debut historical novel ‘Dark Aemilia’ is published by Myriad Editions and Picador US. She works as a lecturer in Creative Writing at the Open University. She blogs here and you can follow her on Twitter at @sallyoreilly

Comments