As a short story publisher, I’m in the business of championing the short story form and its writers. At Dahlia Books, I solely commission short story collections and meet many writers who often dream of making a living from writing short stories without succumbing to the pressure of writing a novel. They are often surprised when I tell them that Mavis Gallant made her living writing and selling short stories, the first of which was sold to The New Yorker for $600 in 1950. It horrifies me that more than 70 years on we are no longer able to do this, thanks to high living costs and publishing monopolies. It’s a zero-sum game to discourage these writers, telling them that there is no commercial value in writing what they love and to spend their time working on a novel instead. It snatches away their creative freedom leaving them to undertake the mammoth task of spending several years learning and unlearning how to work on something much longer than they are used to.

I’m not surprised that many resist. Imagine if you’ve nailed writing a compelling, original story (or several for that matter). Each one beautifully formed and no more than 3,500 words, but everyone in the industry you speak to suggests that to be ‘successful’ you need to write something that’s at least 50-70,000 words. It seems a gross injustice even to suggest such a thing, knowing that Gallant was able to sustain herself in 1950’s Paris from mastering the form and in the knowledge that author earnings continue to fall, with many novelists having to top up their income with teaching or other such work. The precarity of writing success and dwindling incomes was the subject of a recent Guardian article. It was much discussed on social media for it laid bare the hidden cost of being a novelist, the toll it takes on your mental health and wellbeing when your book is literally left on the shelf, and the inevitable fallout when the book fails to hit its sales targets.

For a moment let’s consider that you act on the advice of someone you met at a literary event or a helpful soul in your writing group who insisted that the novel is where it’s at. It’s the mountain you must climb to be ‘successful’ or worse still, a ‘proper’ writer. And you do it. You sign up for an evening class, or take out a loan to undertake an MA, or worse still, a PhD, hoping to learn everything about the novel and get it published. Only to learn, that when you do, the publisher doesn’t have enough of a budget to really promote the work you spent years labouring over and now you’ve signed a two-book deal for less than the average annual income in the UK, and you’re now ploughing through book two at a pace slower than a snail. You might spend five or even 10 years like this, in a literary desert where your book one is out and yes, you do get to do some events and meet readers, and that’s all very lovely but you’re no better off than when you were writing short stories. Your royalty payments will only land in your bank account once you’ve earnt out your advance if you were fortunate enough to receive one, and you have the burden to deliver that second manuscript while living off nothing but bread and tea for the next six months. To sacrifice a much-loved short story practice for this seems perverse or an act of deliberate self-harm.

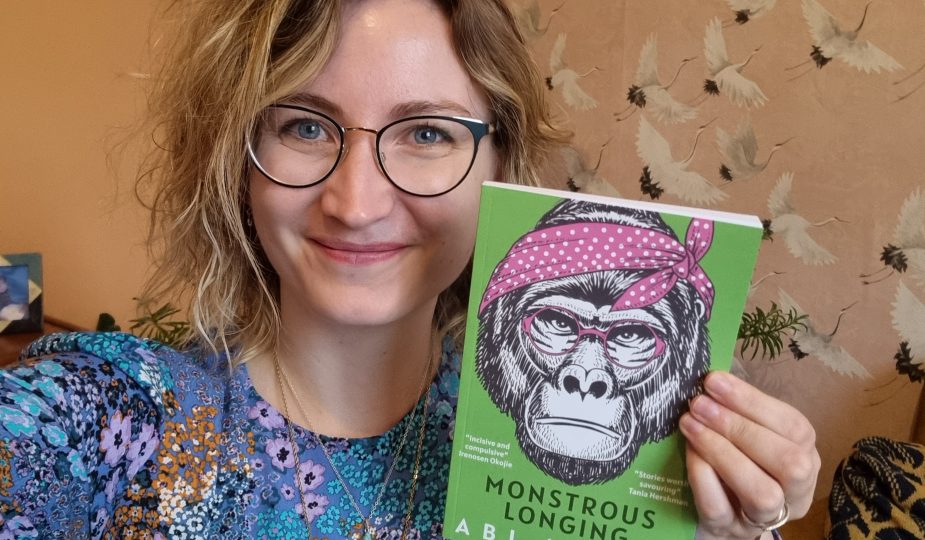

Short stories, if we gave them their fair share of attention within the literary world, can be a crucial part of the infrastructure and they can help writers survive. For Abi Hynes, whose debut collection Monstrous Longing has just been longlisted for the Edge Hill Prize, writing short stories has been the way that she's honed her craft and kept working actively as a writer, as part of a portfolio career.

This is not to say that writing short stories is ‘easy’ or ‘easier’. As a short story reader and publisher, I have had the pleasure of revelling in the evasiveness of the form, that allows writers to be playful, experiment, make it their own. This autonomy is critical if we are to exercise a degree of agency when navigating a career in writing. None of us will follow the same path. To sustain ourselves and our practice we must take ownership of lofty terms like success and reframe rejection. We must, always, resist bad ideas, rules that don’t work for us, and write with abandon for ourselves first.

Monstrous Longing by Abi Hynes is published by Dahlia Books.

Comments