Author Louisa Treger discusses writing biographical fiction, and how to successfully merge fact and fiction.

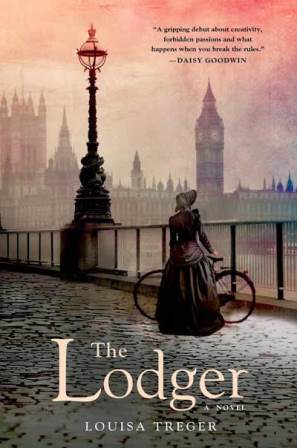

Recent years have seen an increase in the popularity of ‘biographical fiction’: novels and films based on real lives. The Hours by Michael Cunningham, The Paris Wife by Paula McLain, With Billie by Julia Blackburn, and Allan Massie’s Roman Quartet based on the lives of Antony, Augustus, Tiberius and Caesar, are but a few examples. My first book, The Lodger, is a biographical novel about Dorothy Richardson, a little known writer who was a peer of Virginia Woolf, a lover of H.G. Wells, and an innovator of modernism.

I have often been asked what made me want to write a fictional account of Dorothy Richardson’s life, rather than a straight biography, or a novel inspired by her work. This article will attempt to provide an answer, as well as exploring the issue of the writer’s responsibility to the truth when presenting an imagined version of a real life.

My novel is a melding of fact and fiction, broadly following the known biographical outline of Dorothy’s life. Where it suited my purposes, I took certain liberties with the facts and the time scheme. For instance, in reality, Dorothy’s friendship with H.G. Wells developed into a love affair over a ten-year period, but for the sake of narrative impetus, I fast-forwarded and had him seduce her during the course of one spring. I also chose not to write about the Wells’ two young sons. By Wells’ own admission, his children’s early care was largely entrusted to nurses and governesses (H.G. Wells in Love); moreover, Dorothy didn’t appear to have had a relationship with either of the boys.

Do these liberties matter? Is the responsibility of a biographical novelist to fact or to fiction? Can one get closer to a person’s mind and spirit through fiction rather than through fact?

Michael Frayn’s play, Copenhagen (1998), is a fictional recreation of a heated real-life exchange between two scientists in 1941. Werner Heisenberg wanted to harness the power of the atom for Germany’s forces. Niels Bohr, his former doctoral supervisor and mentor, was devastated that his native Denmark had been occupied by the Third Reich. The content of this meeting has always been shrouded in ambiguity. Huge issues were at stake, yet no agreement was reached. In his postscript, Frayn makes the following observations about his attempt to fill in these gaps in history:

'The great challenge is to get inside people's heads, to stand where they stood and see the world as they saw it, to make some informed estimate of their motives and intentions. The only way into the protagonists' heads is through the imagination.'

In other words, engaging imaginatively with the past creates an interlacing of fact and fiction; a space in which the feelings behind the ideas are brought to life.

As Lisa Jardine writes for the BBC’s A Point of View:

'Fiction has the power to fill in the imaginative gaps left by history. … Sometimes it takes something other than perfect fidelity to sharpen our senses, to focus our attention sympathetically, in order to give us emotional access to the past. Silence comes between the historian and the truth he or she looks to the sources to reveal. Thank goodness for the creative imagination of fiction writers, who can reconnect us with the historical feelings, as well as the facts.'

This brings me to the core of why I am drawn to biographical fiction. Dorothy’s life provided me with a framework of interesting and little-known facts on which to hang my story: she was an unconventional and utterly original woman, smashing just about every boundary and taboo going – social, sexual and literary. Yet at the same time, there was enough wiggle room to gain emotional access to the past. Unlike my non-fiction sources, biographical fiction gave me licence to imagine myself into the characters’ private thoughts, to invent conversations and details which drew out themes I found interesting. For instance, Wells’s wife, Jane, was Dorothy’s oldest friend. What did Dorothy feel like betraying her, while in the grip of such a powerful attraction to Wells that she couldn’t draw back? Biographical fiction harnesses the liveliness and veracity of fiction writing. It allowed me to animate my characters’ conflicts, while staying as true to their personalities as I could. The outline of the plot was already there; within that given framework, I was able to create my own image of real people.

I would like to end with a point about the authenticity of conventional biography. Biography is only as reliable as its sources: it can be made up from letters and friends’ reminiscences, which are less than objective. For this reason, fictional biography may be more honest. Of course, one can argue that all fiction is lies, but biographical fiction might be a lie through which the truth can emerge. We all carry our own subjective impressions of people: biographers, as well as novelists, cannot help but view the world through their own subjectivity. Prominent figures from Henry Kissinger to Virginia Woolf have had multiple conventional biographies written about them, which portray them very differently. Everyone has a different image of the same person. Somewhere within that myriad of images the truth lies. The Lodger was my best shot at presenting my own sense of Dorothy.

Louisa Treger began her career as a classical violinist and worked as a freelance orchestral player and teacher. She subsequently turned to literature, gaining a PhD in English at University College London. Married with three children, she lives in London. The Lodger is her first novel. Find out more on her website, and follow her on Twitter and Facebook.

Comments