Author Claire King gives advice on developing your style and writing a novel in the voice of a child.

One of the questions I’m asked most about The Night Rainbow is the rationale behind - and challenges of - writing a novel in the voice of a five year-old child. Some find the idea of it off-putting, whilst others find it intriguing. To my relief, the vast majority of readers have, in the end, appreciated Pea’s voice. But not all. Here are a small selection of comments from readers’ reviews:

“Margot and Pea are amongst my favourite literary children, and Pea's narrative voice was captured perfectly.”

“Her narrative voice is older than five. Which is a shame.”

“The voice of Pea is marvellously written, amusing and sad.”

“The narrator in no way sounded believable as a little kid.”

“It's told by a very poetic and observant 5 year old so the language is rich and pure.”

Writing a novel - particularly a debut novel - in the voice of a young child leaves you open to criticism, or at the least the use of ‘courageous’, ‘bold’, and various other euphemisms for ‘the author must be crackers’.

But of course there are precedents set that show it can be done well and done successfully. So the questions you have to ask yourself as a writer are “Why do I want to use a child’s voice?” and “How do I get the voice as I want it?” (NB, not “How do I get the voice exactly right?”because there’s no way to pitch a child narrator’s voice so perfectly that it will convince and please every reader).

Why use a child’s voice?

You need a compelling reason why a child is the right person to narrate your novel. When I began The Night Rainbow initially it was Maman (Pea’s mother) who told the story. But it soon became clear that the most important viewpoint in the book was Pea’s: oldest daughter, suddenly burdened with responsibilities and trying to make sense of her world which has not only been shaken by tragedy but by the withdrawal of those she relies on most.

Maman stares at me and now she doesn’t say anything. Her face is screwed into a question mark, but I don’t know the answer.

I could still have chosen to write the story in Pea’s adult voice, looking back at her experiences as a child. The child-protagonist in To Kill a Mockingbird, Scout, is only six years old, but the story is narrated by her as an adult, recalling how she saw, and often couldn’t understand, the world at that age.

The advantage of using an adult voice looking back is it allows the author to superimpose a mature understanding over that of the child, and to make the narration more palatable through more sophisticated language. But the only adult perspective I wanted in The Night Rainbow was that of the reader, for two reasons.

Firstly, a child’s viewpoint can help challenge how we would judge other characters’ actions. We are often invited to dislike characters and apportion blame, but is that always necessary? In The Night Rainbow, Maman is wracked with grief and this, combined with the last months of her pregnancy, conspires to make her extremely neglectful of Pea, both practically and emotionally. From what we see of her it would be easy to judge her and condemn her as a bad mother. But when she is seen through Pea’s eyes it is clear she is loved, and I think that helps us to empathise with her too.

Secondly, using a naïve or unreliable narrator changes your relationship with the reader. You’re inviting them to get intimate with the protagonist, see the world through their young eyes but also to interpret it with their own. A child’s words can be deceptively simple, whilst illuminating complicated issues.

We have to do something grownup, says Margot. Maybe we should call the police?

How do you call the police? I say.

I don’t know, actually, says Margot.

The trick is in laying the trail of clues for the reader to pick up – the behaviour of other characters, the environment, ambiguous phrasing of dialogue - it’s the epitome of ‘show don’t tell’ and can be very exciting to write.

How to get the voice as you want it?

It’s interesting that some reviewers comment on whether or not they found Pea’s voice to be ‘realistic’. All voices in fiction are constructs, and I don’t believe authenticity is as critical as a voice that is engaging enough to allow suspension of disbelief.

In finding your voice, do some research. Listen to the speech patterns of children the approximate age of your narrator. Ideally engage them in conversation. My two muses were aged 4 and 2 when I wrote The Night Rainbow and many of their idiosyncrasies and turns of phrase made it into the book. Two years later, when I was copy-editing I would ask them to describe things, like ‘what is the sound of rain on the roof?’ And then change ‘hammering’ to ‘clattering’.

When finding the right voice, you’re not obliged stick to the limits of a child’s vocabulary. Rather, get to know her, try to find your way into her thoughts, even if she doesn’t have words to express them, and write that. A child narrator isn’t writing the book, or dictating it; she’s telling it and you’re allowed to be in her head.

The internet says they just disappear, says Margot. Think about it. If all the dead and broken things had to be put somewhere then our planet would just be a big pile of dead and broken things and we’d have to be climbing over it all the time.

The other challenge is keeping your narrator’s voice consistent. Different writers have different ways of doing this. Mine is simply to read the manuscript aloud – at least two or three times, ideally using a printed copy – and edit ruthlessly. Anything that sounds clunky or out of character, change it or lose it.

There will always be readers who don’t get on with the voice you have created, but that’s the same for all novels. And some of the most wonderful reviews I’ve had for The Night Rainbow are from those who have fallen in love with Pea and her view of the world. It’s the most magical and rewarding thing for me as a writer to have pulled that off. When it happens I feel like a magician.

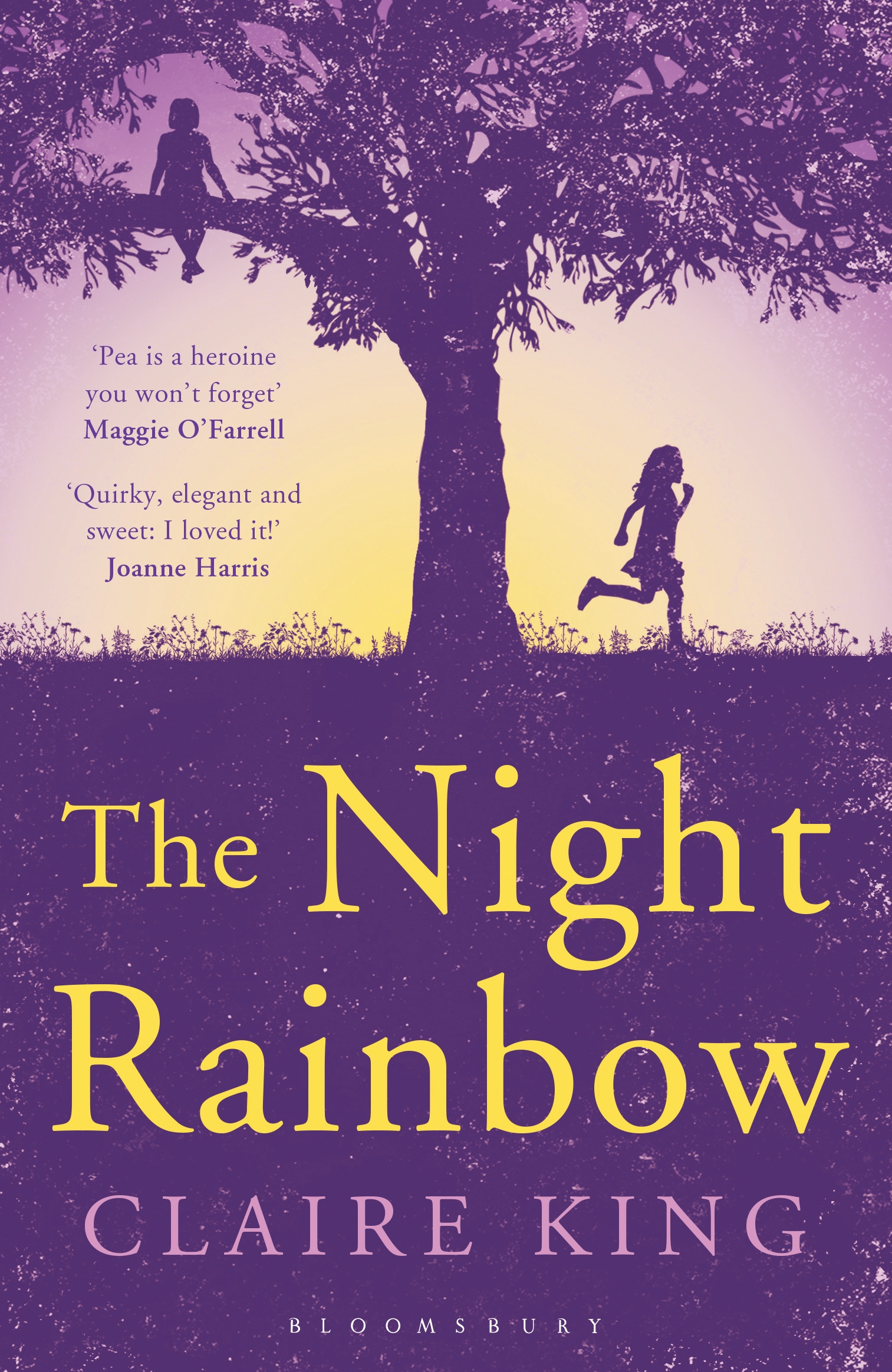

The Night Rainbow by Claire King is published in paperback by Bloomsbury Publishing. Find out more about titles and buy the latest releases from Claire King at Bloomsbury.com

Claire King's debut novel, The Night Rainbow, was published by Bloomsbury in 2013. She is also the author of numerous prize-winning short stories. After fourteen years in southern France, Claire has recently returned to the UK and now lives with her family by a canal in Gloucestershire.

Comments