We all have boundaries in life that we won’t cross.

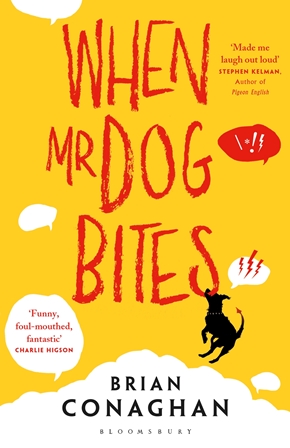

There are certain viewpoints that our conscious simply won’t allow to be verbalised. You know the ones I mean: those thoughts that swim around in the deep recesses of our mind. There’s no way we will ever say them, there’s no way we will allow ourselves to be classed as being intolerant, bigoted, racist, sexist, extremist etc. It’s our internal mechanism of protection, I suppose. However, as writers we have the ability to tackle these traits head-on by shielding behind the voice(s) of the character(s) we create. But should writers have boundaries themselves? No-go areas? Or is creativity a blank canvas where everything and anything is fair game? These are questions that have been posed to me since the publication of my YA novel, When Mr Dog Bites.

In this novel there are some characters who are indeed intolerant, bigoted, racist, and downright unsavoury. Within the pages these characters use words and phrases that society frowns upon; they demonstrate a linguistic proficiency that would shame their parents and elders. Moreover, my main character, 16 year-old Dylan Mint, who I believe is a great little guy, curses like a drunken docker. While Dylan is funny, warm, kind-hearted, sensitive, compassionate, angsty and clever he does use an alarming amount of profanity. I should point out at this juncture that Dylan suffers from Tourette’s Syndrome so some of his vulgarity is pretty much unavoidable really; unavoidable if the portrayal of his condition is to be dealt with honestly and accurately.

When I set out to write When Mr Dog Bites all I wanted to create was an entertaining book that teenagers could enjoy and/or engage with, and perhaps channel a discussion around some of the more ‘controversial’ issues within the book. After over a decade of teaching English to secondary school students I allowed my own hubris and knowledge of teenagers to guide me here. What I certainly didn’t want to do was offend any of my readers. Nor did I want to patronise, condescend or lecture them either: an offence in itself. In my experience I have found teenagers to be the most ardent reviewers of books, they consider them in finite detail and generally provide a considered and impassioned critique of what they’ve read. Most adult readers don’t.

Recently The Telegraph newspaper in the UK sparked an online debate when it published an article entitled “Should potty-mouthed children's books come with a PG certificate?” This article was pertinent to myself because The Telegraph’s Online Culture Editor used When Mr Dog Bites to cement his argument and stoke the debate. I’m guilty as charged: Mr Editor was on the money: the characters in my book do use bad language. They do use profanities and they do use some objectionable words and phrases. I hold my hands up.

The question posed to me at the time, and even now, is why? Why, Brian, especially in YA fiction is it necessary to litter it with coarse language? Good question. Let me think about it, I say. In truth I don’t need to think about it because my answer never wavers:

Aside from the issue of Dylan Mint’s Tourette’s, I wanted to portray accurately and honestly the teenage voice in the town where When Mr Dog Bites is set. This is a setting I’m more than familiar with. I lived there. I worked there and I spent my teenage years there. My family and friends still live there. So, to present a sanitised version of the characters’ voice would have been inaccurate, dishonest and misrepresentative on my part. It would have been a fraudulent.

Surely teenagers have had enough of adults speaking on their behalf, thinking they know what’s good for them. People have to acknowledge the different social and cultural climate we now live in and stop believing they know what’s best for our youth. If we seriously wish to create the informed, impassioned and insightful minds of the future then high-jacking their voices is not the best start. Let teenagers decide what to read. Let them be the ones to complain if something is unpalatable. Let them be the ones to say THANKS, BUT NO THANKS. The amazing thing about bookshops and libraries is that people are not frogmarched inside and forced to read any particular book; they can opt out and choose whatever they want. In fact, everyone has a choice, parents included.

The content of When Mr Dog Bites resurfaced discussions I’d been having for over a decade in my capacity as a secondary school English teacher. I spent everyday of my working life with teenagers; hearing their conversations and idle chat and listening to a discourse that was littered with swear words: words used to express humour, anger, emphasis, frustration, opinion, objection, foible etc…sure, we all do it, don’t we? It’s the reality of how language functions in my part of the world, I’m afraid. Surely we don’t want to create a Nanny State whereby depictions of reality within some of our books is frowned upon by those who don’t understand, or haven’t experienced, such reality, do we? In an ever-increasing world of reluctant readers and ailing literacy levels I for one would be celebrating the fact that children, teenagers and young adults are actually engaging in the act of reading before I’d censor their material. If publishers start putting a succession of $£@* symbols into books instead of letters then we’re all doomed. It would be counter-intuitive in any case; all we would be doing is placing the word inside the readers’ head: reinforcing it, cementing it, making them say it; absolving the publisher and the writer from their responsibility. No, these words in When Mr Dog Bites are all my creation; I’m the one who’s accountable for them.

President Putin passed a law recently that will require books containing swearing to be sold in sealed packages with explicit-language warnings covering them. Perhaps in Russia the packaging for When Mr Dog Bites will have to be surgically removed before the opening sentence can be read. Let’s face facts: language exists, it evolves, it grows, it’s the only weapon of the sub-cultures, the working classes, the ghettoized and the majority. If we start to control and impose authority over what we say and create the next thing to go will be our thoughts. Think about that.

Or then again!

Brian Conaghan was born in 1971. He was raised in the Scottish town of Coatbridge but now lives and works as a teacher in Dublin. He is the author of The Boy Who Made It Rain and has a Master of Letters in Creative Writing from the University of Glasgow. Over the years Brian has made his dosh as a painter and decorator, a barman, a DJ, an actor, a teacher and now a writer. He currently lives in Dublin with two beauties who hinder his writing: his wife Orla and daughter Rosie. Find out more about When Mr Dog Bites here and follow Brian on Twitter.

Find out more about titles and buy the latest releases from Brian Conaghan at Bloomsbury.com

Comments