My young daughter is a child like any other – she reads books, she climbs trees, she digs about in dirt, she laughs at jokes about poo, and occasionally (when she’s been very good and only as a special treat, you understand) we watch cartoons together.

There’s one she’s particularly partial to, which features a boy character and a girl character. The boy character happens to be an elf and the girl a fairy, and they are best friends. In most respects, the cartoon is very enjoyable, but in episode after episode I find myself gritting my teeth in frustration at the limitations placed on the fairy character – often by her own assumptions about herself – and the opportunities offered to the elf character. Most of the main fairy characters are girls (there are boy fairies, but they’re not important to the plot of any episode I’ve seen) and similarly the important, plot-relevant elves are all boys. In nearly every episode, the doughty elves take on the challenge of the day with a confident, self-assured battle cry, letting everyone in earshot know that they’re good at doing things – because they’re elves.

In my ears, those words always ring as: We’re good at doing things – because we’re boys.

To her credit, my daughter has always told me she’s an elf. She identifies with the elves, with their self-belief and can-do attitude, and when we’re playing at being characters from this cartoon she is always an elf. I love this, and have never dissuaded her. I would prefer she sees herself in a character who does things, who is active, who shows initiative, who believes in themselves, and who is unafraid to say so.

It would be nice, however, if – just once – these self-assured and capable characters could be the girls.

In the most recent children’s books I’ve read, the situation is a little better. My daughter’s picture books are full of cheeky, quirky, cheerfully disobedient girls, and books for older children abound with girl characters who are multifaceted, interesting, and self-assured. However, it can be harder to find boy characters who are vulnerable, emotional or expressive. As important as it is to show girls that they can lead, be strong, be scientists, be inventors, and save the day, it’s just as important to show boys that they can cry, be beaten down, express feelings – and still be heroes of their own story. I recently read an excellent book in which the main girl character sets out to prove she is every bit as good as a boy (and she is), and the main boy character is determined to find his true parents. This was such a refreshing, satisfying tale simply because the reader’s expectations are subverted somewhat; the girl gets to be brave, eager, a bit reckless, and not at all attached to sentiment or a desire to conform, and the boy is the one to suffer loss and deal with the resulting emotion, and to have his story arc focus on finding his true home. I enjoyed the book not only for its use of magic, mystery and action (all of which it does wonderfully), but mostly because of the strength placed in its female lead and the vulnerability placed in its male lead.

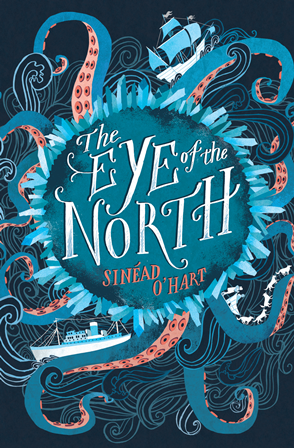

The protagonist of my children’s book The Eye of the North is a girl named Emmeline Widget. She is (and I’m allowed to say this, because I made her) a little odd. A child who prefers her own company, she is anxious and prone to over-thinking, as well as profoundly suspicious of the world, other people, and most of the things she encounters. Emmeline is scientific, rational, and cool, and she would never be caught making a rash decision.

She’s also unemotional – or at least she appears to be. Inside she is a maelstrom, as are most of us, feeling fear, anger and worry at various points of the story, as well as a deep love for her family and newfound friends which she finds it hard to express. On her journey to a new life, she meets a nameless boy who calls himself Thing. He is impulsive, emotional, fun-loving, a natural ‘people person’, and he is the one called upon to deal with a painful, repressed event in his past which brings up feelings long ignored. Both Emmeline and Thing grow over the course of the book, and they’re equals when it comes to their importance to the story, but – makers of my daughter’s favourite cartoon, take note – Emmeline is not a passive character who waits around to be rescued, and neither is Thing the all-action hero all the time. Emmeline is a girl like I was; quiet, bookish, nervous and introverted, but full of strength. There weren’t many girls like me in the books I read as a child. I really wish there had been.

One of my recent reads was an otherwise brilliant book which was spoiled slightly by one wince-inducing line; a character (a baddie) is described, pejoratively, as ‘screaming like a girl’. This raised my hackles, and made me realise that as long as we keep writing stories wherein to be ‘like a girl’ is to be a bad thing, how can we expect girls to want to excel, and boys to see girls as their equals? Every child deserves to find themselves in books, and it’s our privilege as writers to deliver stories worthy of their readers – whatever stereotypes we must undo to make that happen.

Comments