Debut author Fran Cooper discusses the importance of using your voice as a writer.

‘Find your voice’ might be the most daunting thing you can say to a writer. What do we even mean by ‘voice’? It is everything, to a novel, and yet nothing that you can precisely put your finger on. Tone, nuance, flow, form – ‘voice’ might mean a hundred things to me, and a hundred different things to you. It is terrifyingly abstract; an intangible quality that draws you into the very best books, sometimes without you even noticing it. It is not something you can ‘find’ as if on an authorial treasure hunt or bookish game of hide and seek. My advice? Don’t agonise over finding your voice – use your voice instead. In my experience, it’s the best free tool you didn't know you had.

Four years ago, I was lucky enough to be living in Paris, where I stumbled into a fantastic writing community. Every Monday night, crowds of people would gather in a dark, sweaty basement in the 11th arrondissement for an open mic night. Anyone could perform anything – poetry, songs, stand up. The only rule was that you had a five-minute time limit. For a whole five minutes, the stage was yours.

I spent my first few weeks at this event in awe of the poets and songwriters who got up so boldly to share their work. I was itching to get onto the stage, but I didn't write poems or sing songs – I only wrote prose. It’s so much easier to perform songs and poems, I kept thinking to myself. They have rhythm. But of course, when I finally got up the courage to perform, right at the end of a night when the crowds had thinned out a little and those who were left were pleasantly buzzed with cheap French wine, I realised what I’d known all along. That obviously prose has rhythm too.

When you stand up to read a short story to a basement full of strangers, it has to pack a punch. It has to sing. There’s no room for anything extraneous, nothing rambling or self-indulgent. When you have five minutes to get through a beginning, middle and end, and make people feel something, every word counts. Reading aloud to a room full of people, I learned immediately what worked and what didn’t. What looked impressive on the page but was tongue-tangling terrible out loud. What made people gasp or smile, what elicited a chuckle or even a sigh. The first time I read a story out loud, I shook like a leaf. But over the weeks and months, my confidence grew. And I found that reading my stories out loud helped me find that strangest, most elusive of writerly things – my written voice.

Back in 2009, I heard Zadie Smith give a lecture about writing. I remember vividly her advice that there is no better moment to edit than when you’re holding the finished book in your hands and you’re about to go on stage and read from it.

Not everyone has an open mic night at their fingertips – and not everyone would want to go and read their work aloud to a group of strangers. But I believe these lessons can be transferred to other writing environments. The same people who organised the open mic in Paris also ran a writers’ workshop. Again, you could bring poetry, fiction, non-fiction, but here the golden rule was that somebody else would read your work to the group. If you spend three hours agonising over a page of prose, you know exactly how it’s meant to flow. You know, in your head, how it should sound, what word comes next, where you want the pauses for dramatic effect. Someone looking at that page for the first time doesn’t know that. And I found that hearing them read it – hearing where they put the emphasis, where they stumbled, where they hadn’t quite understood what I was getting at – was enormously valuable.

I don’t live in Paris any more, and once I started writing novels it became harder to share these little beginning-middle-and-end vignettes at writing nights because my mind was focussed on a larger project. But I still read aloud to myself (and my cat) while writing. I ask my other half to read things out just to hear what he makes of them. When I’m stuck in my head, I read my words back to myself. As a writer, you already have a voice – you just need to use it.

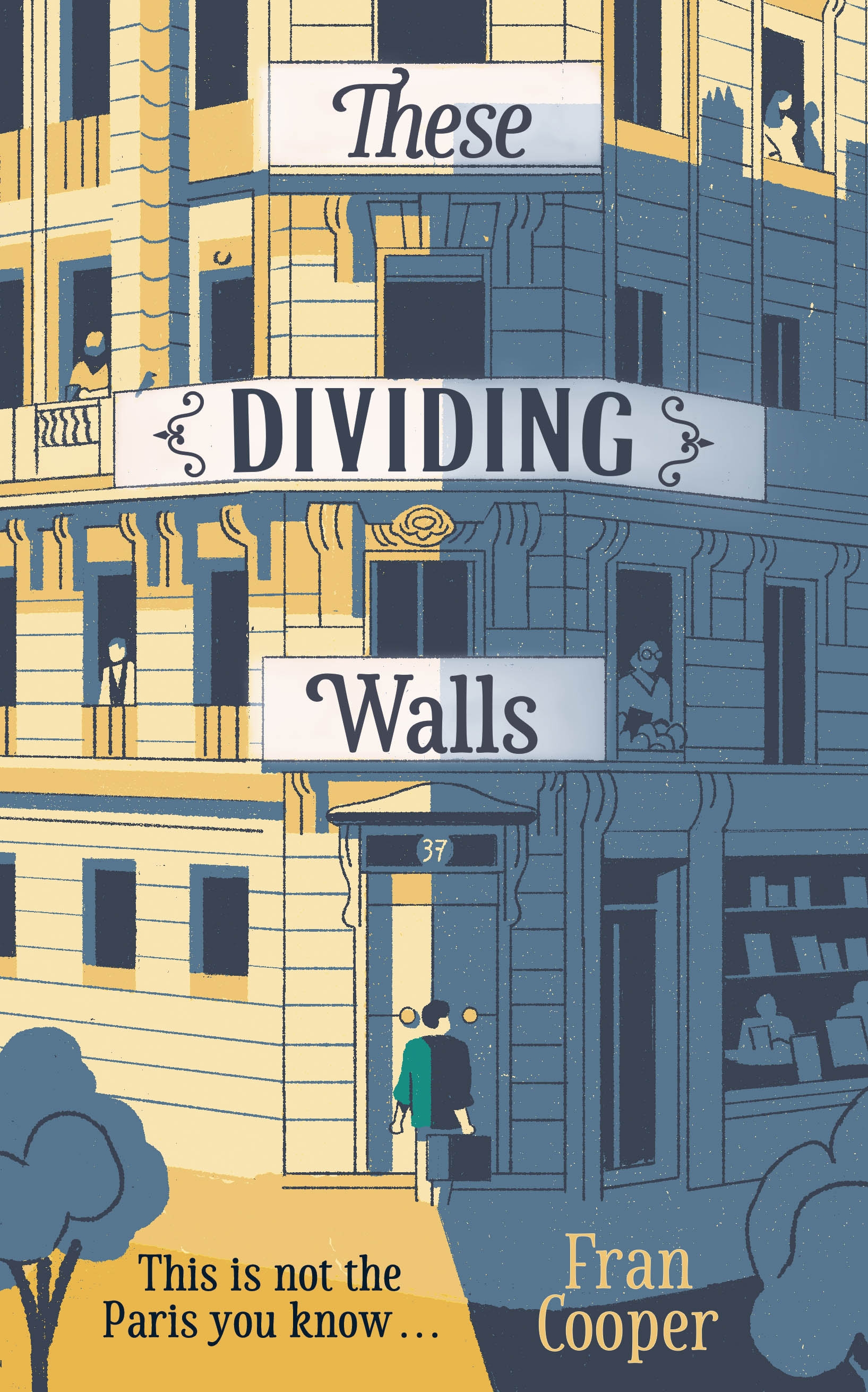

Fran Cooper grew up in London before reading English at Cambridge and Art History at the Courtauld Institute of Art. She spent three years in Paris writing a PhD about travelling eighteenth-century artists, and currently works at a London museum. These Dividing Walls is her first novel and was published in 2017. Visit Fran's website here and follow her on Twitter.

Comments