Learning when to take feedback to heart and when to ignore it is an important part of a writer’s skillset, says crime author Heather Critchlow

Giving and receiving feedback on writing can be a minefield. As fledgling writers, it’s something we come to with very different expectations and tolerances. Writing is so subjective, and finding a gold standard is impossible. Instead, it’s a lifelong process of learning the rules (so we can decide when to break them), seeking inspiration and developing a canny inner editor.

As well as reading analytically, a key way to develop these instincts is to put ourselves out there and make your writing available to others who are willing to offer constructive feedback. Yet finding beta readers isn’t always easy. If you are able to join a course or workshop, that’s great, but this isn’t possible for all. Are there local writing groups that you could join, festivals you could go along to or online groups that you could connect with? Getting to know other writers means you are likely to find people willing to spend time reading – and offering suggestions on – your work.

An important word of caution to flag at the very outset: if the dynamic isn’t quite right … walk away. The experience of receiving feedback might be exacting but should be constructive and never bruising or unpleasant. Don’t put yourself through that.

To help offer a more rounded view of the process of receiving feedback, I spoke to a few people within my own writing network to get their take on what is such a sensitive yet important aspect of the creative journey.

Feedback should be neutral

Jo Furniss is the author of three published novels. Her latest thriller, Dead Mile, is released by Bonnier in 2024. She also runs a weekly group in Hove, where writers at all stages read their work at open mic nights and share extracts for feedback.

“Critique doesn’t mean the same as ‘criticism’,” she says. “Feedback isn’t positive or negative, nasty or nice. It should be neutral. Published writers receive several stages of notes throughout the editorial process, all designed to make the book the best it can be, to iron out anything that may distract the reader. We try to hit a similar professional tone in our group – it’s not personal, not a verdict. I’m happy when writers go away from a critique session fired up to attack the second draft.”

Jo says that writers have three options when receiving a critique – to adapt, adopt or ignore. “If you disagree with a point, feel free to ‘ignore’ – after all, every reader is subjective. If you agree with a point but not the suggested solution, then ‘adapt’; re-work the text in your own way. And if a critique partner hits the nail on the head, then ‘adopt’ their feedback – make the change and move on, content that your work has just got even better.”

Running the workshop gauntlet

Those familiar with writers’ workshops are also likely to be familiar with certain ‘types’ that frequent them. On one extreme: the writer who is convinced they have written a perfect novel, ready to accept praise and adulation, and very much not ready to accept criticism. And in the other corner: the underconfident writer desperate to improve, taking all feedback to heart and willing to accept any criticism as gospel. While this person may be easier to get on with, neither approach is particularly helpful.

Instead, I think it’s worth striving to be somewhere in the middle – attuned both to good advice and ready to quickly discard that which is less helpful or downright cruel. My own internal editor is a work in progress – always learning and a bit more savvy after a few knocks on the way.

Finding your tribe

I’m lucky to be part of a writing group that meets monthly. We share around 1,000 words each time – sending the extracts in advance and discussing in person. There’s a strong level of trust between us that has been built over years. We started on a W&A course together, where we developed the habit of sharing our work. When the course stopped, we didn’t. Five years on, it’s much easier for us to be candid with each other – we know we have each other’s best interests at heart.

So, what does useful feedback look like to us…

- It’s kind: this isn’t always the case, but in my view the best sort of criticism is given constructively. Writers don’t need to be ripped to shreds to learn.

- It’s applicable to the stage of the writing: in our group, first draft, shiny new idea feedback is different to final draft, nit-picking feedback. The former requires enthusiasm and gentle big picture probing – it’s not the time to be quibbling over language. If you’re seeking feedback, ask yourself if it’s the right time. If someone slams your work, is it going to crush it before you’ve started?

- It’s specific: an agent (not mine) once told me my writing was ‘missing a spark’. Short of setting fire to it, there’s little to go on there. We annotate the text and then discuss in person what we meant. If we’re not sure why something isn’t quite working for us, we unpack it together.

- It makes you go ‘aha’: the clear sign that you’ve had great feedback is when you feel inspired to make changes. Yes, it might sting, frustrate or annoy you as you realise you have a whole load of work to do but ultimately it leaves you feeling galvanised.

- Everybody agrees: we regularly all pick the same word, phrase or paragraph out of someone’s text. There might be five different views on how best to change it, but the overriding (and very useful) message is that something isn’t working – it’s the writer’s call on what to do about it.

- It highlights the positive: it’s worth treading carefully when delivering feedback to someone for the first time. Some people are more robust than others when it comes to criticism. We always take the time to pick out the things we love about each other’s work – beautiful language, deftly-drawn characters and heart-breaking plot twists – as well as the areas that we think need improvement.

Genre expectations

It’s also worth being genre aware when seeking (and giving) feedback as different genres come with different expectations that writers will be trying to fulfil or subvert. Sam Holland, author of thrillers The Echo Man and The Twenty, is published by HarperCollins and has written a further eight books under different names. After years of writing, she says she is careful about taking advice from too many sources.

“You should definitely listen to your editor and agent, but outside of that, the voice you should listen to is your own: your instincts about what works for your book and the characters,” she says. “Beyond that, the best people to help are those who have written and edited books in your genre and who understand what you’re trying to achieve.”

Don’t make the mistake of thinking that because the feedback comes from someone in a position of authority or experience it is definitely right. This is a hard one to learn. Even agents, editors and course tutors can be wrong about your book. Maybe it’s just not their cup of tea, or maybe you aren’t ready yet, but that doesn’t mean you won’t be. If it’s delivered unkindly, this kind of criticism can be devastating but it doesn’t mean it’s the final word.

Career preparation

Ultimately, feedback is something writers need to get used to. Niki Mackay is the author of six crime novels and teaches creative writing for several academies. She has two novels out later this year: The Quiet Dead will be published by Hera in September and Due Date will be published by Headline in October.

“By the time I’ve delivered a manuscript I’m normally quite confident that I have made it as good it can be and I now need to ‘open the door’ for feedback,” she says.

“From here on in it’s a joint effort. Once you’re published the opinions that matter most are your agent and editors. Editing is elevation and all writers will need it to some degree so it is useful to get used to receiving it in good grace. Writers groups and short courses are good for this. But any friend or family member who is an avid reader in your genre can probably tell you what’s not working.”

Feedback and critique are gifts to writers. But learning what to do with them is crucial – as is honing and trusting your instincts. Depending on your temperament, it’s tempting to take every comment to heart. Resisting this will come in handy when those first NetGalley reviews and Amazon ratings roll in down the line…

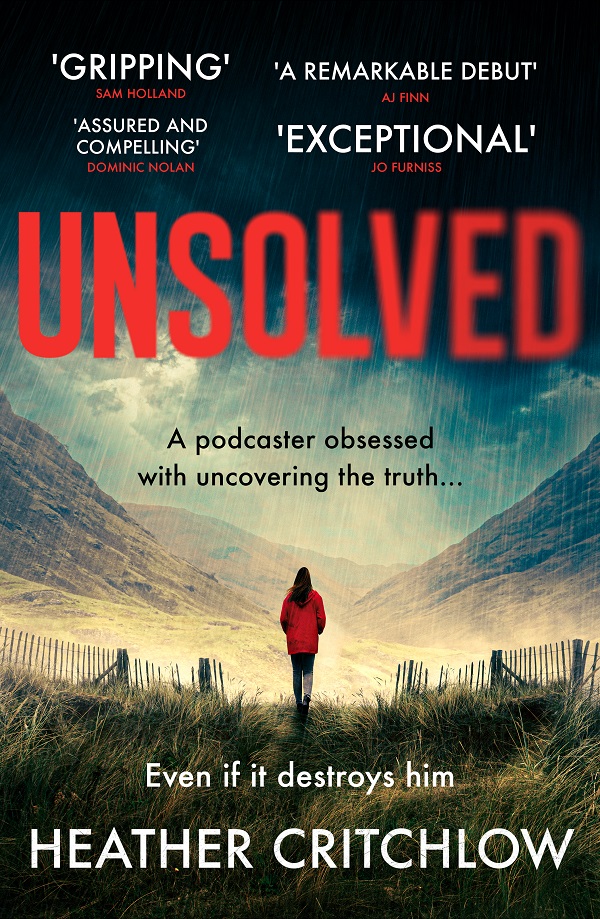

Unsolved by Heather Critchlow is published by Canelo and available now

Heather Critchlow grew up in rural Aberdeenshire and trained as a business journalist after studying history and social science at the University of Cambridge. Her debut novel Unsolved is published in May 2023 by Canelo and is the first in a three-book series featuring true-crime podcaster Cal Lovett. Her short stories have been featured in the Afraid of the Light anthologies, collections of stories written by crime writers. She lives in St. Albans, UK. Find her on Twitter @h_critchlow, on Instagram or at www.heathercritchlow.com.

Comments