Ahead of their workshop on Writing & Illustrating Picture Books on Wednesday 23rd February, Harry Woodgate shares their five tips for growing a picture book idea.

So you’ve got an idea for a picture book, but you’re not quite sure how to develop it into a story yet. Whether you’re a first-time writer, an author who’s written for other age groups before, or an illustrator who’s interested in writing your own stories as well, the aim of this article is to help you grow your idea from a small seedling of inspiration into a full manuscript.

Generally, picture books are made up of 32-36 pages, or 12-14 spreads. Word counts can vary between around 500-1000 words. You might think that because of these constraints, picture books are easier to write… in which case, you may be disappointed! Every word and illustration must earn its place, which means being creative in how you choose to tell your story – and sometimes quite ruthless in what you leave out!

So, what makes a great picture book? Every writer will answer this differently, but here are a few key elements I like to focus on when I’m drafting a story.

- Purpose

- Character

- Structure

- Language

- Word & Image

1. Purpose

Not to be confused with porpoise, although maybe there’s a picture book idea in that, too. Like all stories, picture books need a purpose – a spark that drives the story and gives the whole thing reason to exist. Identifying your book’s purpose early on can help guide the way you craft characters, plot, and illustrations, but without it, a story can quickly fall flat.

Your book’s purpose might be to improve a particular kind of representation, to teach young readers about a certain topic, or simply to make kids laugh out loud, gasp in wonder, or feel comforted when they’re upset. Whatever it is, the most important thing is to make sure it’s relevant and relatable to young readers.

2. Character

Some of the best picture books feature truly memorable characters who children want to spend time with again and again. Think about what makes your characters believable, relatable and compelling.

-

What are their motivations, goals, and flaws? What obstacles do they face, and how will they overcome them? What are their unique quirks and traits? Just because you’re writing for young readers doesn’t mean your characters have to be less complex – children will quickly see through one-dimensional characters.

-

Are their stories and identities authentic? Are you the best person to be telling those stories?

-

Are they human or animal, and why? Animal characters can be useful when featuring a human child would be inappropriate (eg. being eaten by a crocodile; being flattened by a piano, etc), but allowing children to see diverse, inclusive and accurate representation in books is SO important.

3. Structure

Picture books are such a condensed format, so pacing is essential. The structure of your story often needs to pull as much weight as the words and illustrations themselves.

It can be useful to build your story around a few key moments. I usually aim to introduce my main premise in the first 1-3 spreads, build up to a turning point on spread 8 or 9, followed immediately by the low point or climax, and finally a satisfying conclusion on spreads 11 and 12. Making a dummy book can help you work out these main beats, as well as help figure out where the best page turns will be.

For illustrators and author-illustrators, artwork layouts are another important thing to consider. Perhaps you might spotlight important moments with full or half-page illustrations, communicate time through sequential panels, or focus in on details with small vignettes. Distributing these appropriately throughout your book will ensure the story flows naturally.

4. Language

With such a short word count, there’s rarely space for lengthy descriptions. How can you keep language succinct and accessible for young readers, whilst also highlighting aspects of the story the illustrations can’t?

Sensory descriptions can be effective – what does your story smell like? How does it sound? Is it hot or cold, sharp or smooth? What is the weight of it? Rhyme, refrain and repetition are good, too. The only thing to consider with rhyme is that it can make translation (and therefore securing co-editions) a bit more difficult.

5. Word & Image

Where picture books excel from a psychological and developmental perspective is how they encourage children to read between the lines and interrogate the relationship between words and illustrations.

Imagine a book where the illustrations simply repeat what’s already described in the text… not very engaging, right? Now imagine a book where the illustrations constantly question, contradict, build upon, and expand the text. The beauty of picture books is in their multimodality – the way these two forms of storytelling interact, like a kind of dance.

When writing, how might you leave space for the illustrations to plant new seeds? How might you invite questions, responses? When illustrating, how might you take elements of the text and illuminate them further? Stretch them, reshape them? Your story exists just as much in the words you choose to leave out; the white space you choose to leave un-illustrated.

You can still book onto Harry's workshop Writing & Illustrating Picture Books on Wednesday 23rd February. This forms part of our Children's & YA Fiction Festival 2022.

Harry Woodgate (pronouns: they/them) is an award-winning author and illustrator who has worked with clients including National Book Tokens, Andersen Press, The Sunday Times Magazine, Harper Collins and Penguin Random House.

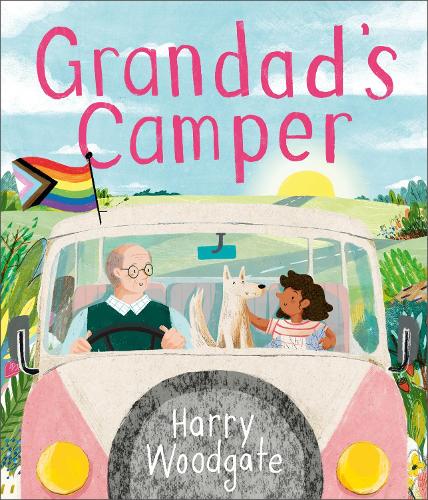

Their debut author/illustrator picture book, Grandad’s Camper, was published in May 2021 and has received Starred reviews from Kirkus Reviews and the School Library Journal, as well as positive reviews from the Bookseller, Guardian, Times Literary Supplement and many others.

They are passionate about writing and illustrating diverse and inclusive stories that inspire children (and adults!) to be inquisitive, creative, kind and proud of what makes them unique.

Comments