Sarah K. Jackson, debut author of Not Alone, offers five top tips on how to build a grounded science fiction world setting.

Science fiction worlds are often distinctive and tied closely to the story. It doesn’t always start out that way—for Not Alone, the characters’ journeys were my way in and the rest grew around them, each then informing the other, getting richer and more cohesive on each successive draft. The resulting world with its microplastics pollution, climate change and altered plants and animals was important—both because this is what Katie and Harry are trying to survive within (it’s intrinsically tied to their story of survival and resilience) and because these are threats to us and our planet that have been on my mind as an ecologist and are now widely talked about. What is distinctive and important about your story? Here are my top five tips for building that world:

1. What key details make up this grounded science fiction world? What marks yours apart?

For Not Alone, research and experience helped with realistic details, like the continuous autumnal-like leaf fall and the specialist survival skills needed to forage and hunt in this altered toxic world. Decide what real facts, places or people you are bringing into the story and how much artistic licence the story needs or is able to carry and immerse the characters and the plot in the small everyday details (as well as the big catchy details such as an apocalypse and most of the population being gone…) to make the world feel believable and lived in. How do people eat, sleep, traverse the world, choose what to wear, care for a child? What does that child play with, what does the air smell like, what do they worry about at night, what sounds or smells are welcome and which strike fear.

2. Create clear visuals.

A striking and clear visual increases believability and immersion for the reader. Give us some details that feel fresh and distinctive and the world becomes more intriguing, set apart from our reality and other similar stories. Think about key features, colours, shapes, lighting.

When I see the sombre colour palette amid bobbing fungal spores catching the light, general rewilded decaying cities and mounds of zombies, I know I’m in The Last of Us. Ashen ground and skies, decay and nothing living: The Road. An emptied, regreening US, a troop of Shakespearean actors in motley outfits, and flashes back to a viral epidemic: Station 11. When you turn each page, you can see where you are.

3. Add all the other senses.

How do your characters experience this world in ways other than visual? Perhaps it’s very quiet outside, other than an ominous rattling of particles against glass. There’s an unpleasant acrid smell of pollution on the air. Sometimes experience of particular locations can inform this, sometimes research is needed, and sometimes it is purely imagination, and the adding in of these small details helps to immerse us further into this world. Senses like smell and taste can also be more emotive than visuals—those parts of the brain more closely connected

4.What is the tone and feel of the setting of your story?

Is it threatening, oppressive, shocking, comforting, nostalgic, hopeful? Often flashbacks or starting the story in the closest-to-normal world invites the reader in and creates a powerful emotional and physical contrast to what comes next. Tailor your details, not just for believability and immersion, but purposefully, to evoke how this new world feels. Show rather than tell, and the reader will experience the danger, the worry, the excitement of being here alongside your characters. Just like with plot tension, the feel of the world should alter and ebb and flow as we build to moments of drama or tension or resolution, and it will linger between and beyond the pages for those who connect with it.

5. Last and most important, what’s enticing and meaningful about this world? Why should we care?

Science fiction, though often set in a future, is often not about future or imagined threats, but about current ones. Asked if I think something like what happens in Not Alone could happen in real life, my answer is it already is, not in quite the same way and not on that scale, but yes, microplastics and climate change are already making localised areas challenging or unliveable. And they’re both already pervasive, it’s ‘just’ a matter of lesser or greater degrees.

Of course, that’s not the only reason to create a science fiction world. Sometimes it is pure imagination and fun, or to explore a political, social, personal issue etc, or pursue the intellectual curiosity of ‘what if’ to its extremes.

Regardless of the reason, there often needs to be a hook, an interesting or strange otherworldliness, grounded in some familiarity on which to suspend our disbelief, that intrigues and captivates. There are always ways to give fresh interest, fresh nuance—post-apocalyptic fiction for example has been a staple for decades and we are still pulled in by fresh takes on the end of the world. The questions it asks seem always relevant: is this what could happen? How do I reconcile mortality and death with hope? How would I, an ordinary person too, manage to survive?

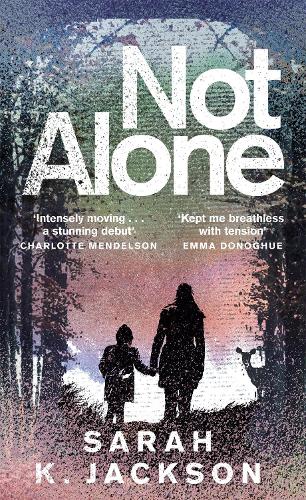

Not Alone by Sarah K. Jackson is published by Pan Macmillan and available to buy now

Sarah K Jackson is an author and an ecologist, who grew up in the Midlands and now lives in Hertfordshire. She studied Psychology and Criminology at Cardiff University and Conservation Ecology at Oxford Brookes University and has worked as an ecological consultant for twelve-plus years, specialising in botany and habitats. Not Alone is her first novel – a post-apocalyptic story of survival and fierce motherly-love and hope – published by Picador in the UK and Doubleday in the US. Follow her on Instagram and Twitter @SarahKarenne

Comments