To write effective poems you have to listen to your feelings but also learn your craft.

Reading as a Poet

To write effective poems you have to listen to your feelings but also learn your craft. You do that by reading-as-a poet: observing how well-made poems, written in today’s language, get their effects. But good poems today are more various than ever before, so where do you find your models? Explore new anthologies, join the Poetry Book Society and receive four new books a year plus discussions of them, join The Poetry Society and receive Poetry Review. Find poems you like: analyse why you like them, what they say to you, and how they say it.

Process: Imagination and the Chisel

You can see the stages of writing a poem as two kinds of sculpture. At first you work with soft material like clay, gathering stuff from your own imagination and the outside world. You are utterly open, listening to everything, inside and out. Once you have a draft, you’re another sort of sculptor: you are facing a block of stone, using a chisel to free the image within, cutting away extraneous stuff: clichés, or lazy, redundant words.

Poetry is the art of saying as little as possible. Every word matters, so challenge each one and ask it: 'Wouldn't my poem work better without you?' Rigorous self-editing is crucial. One of its mysteries is that a word is often most powerful in its absence, when you remove it. Trust your reader to understand implications: good poems don’t spell things out. Use fresh, surprising language, written as you speak. No archaisms. Poetry lives off the living language, words as we say them not as they were in Wordsworth’s day. Wordsworth himself was doing something new, using the speech of “common people”. We should, too.

Pressure and Patterning: You are Your Line-Breaks

Everything depends on the relation of content, what you want to say, to form, the shape you say it in. In physics, time and space are one. In a poem the form is part of the message.

So, form? A poem is a patterning of sound but also of silence, represented on the page by white space pressing in upon the words, so your line-endings, where your words hit white space, are crucial.

Not because of a pre-planned scheme of rhymes at the line ends. Unless you are very experienced, don’t end-rhyme. It is excruciatingly obvious when a word has been chosen only for the rhyme, rhymes are only one way of making a relationship between words, most have been said before, and tired, banal rhymes wreck a poem. Think of rhyme as the white paint which artists use all the time but often doesn't appear as white. Rhyme depends on vowels. Vowels are the emotion of a poem. (You can’t sing consonants). Internal or half-rhymes help a poem cohere, help words belong together.

Choose the word you break the line on with enormous care. Why waste a break on and or the? The last word of the line has maximum stress, do you want to stress 'and' or 'the'? Read your poem aloud, mark the line break, listen for its effect. Vary the types of line-break: on a verb, on two syllables or one. Each break adds to the poem’s emotional journey. .

More patterning: stanzas can be any number of lines but be consistent and make sure each is coherent in itself, that the break at the end of each stanza (as well as each line) is not arbitrary. Check how many beats there are in your lines and make them, too, roughly consistent. Eg a default pattern of five beats which you vary by sometimes lengthening to four or extending to six.

Vivid, Memorable and Concrete: Junk the Abstract Nouns

Poetry gets at universal ideas through the particular, the big idea through the small specific thing. It also needs to be memorable and vivid. Abstract nouns are loose carpet-bags which contain big ideas (like beauty, truth, wholesomeness): they are not memorable and vivid. But concrete examples of them are - and these can hint at the universal without spelling it out. So circle all abstract nouns in your first draft, remove them and find a specific image to convey the thought instead. You’ll find this wonderfully freeing. Your poem will start to live, and may truly become what Robert Frost said a poem should be: “a fresh look and a fresh listen.”

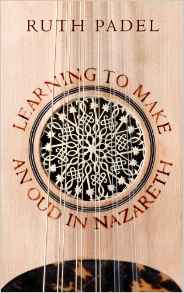

Ruth Padel is a prize-winning poet, Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature. Her latest collection is Learning to Make an Oud in Nazareth, shortlisted for the 2014 T. S. Eliot Prize (Chatto 2014). She teaches Creative Writing at King’s College London. Her books include 52 Ways of Looking at a Poem and The Poem and the Journey (Vintage 2002, 2006), essential guides to reading contemporary poems. Follow her on Twitter or visit her website.

Comments