In these days of tough competition, getting out there, being visible and promoting your books is an essential part of a writer’s job. More and more often, we leave behind the relative security of our desks and head out into the big, scary world of literary festivals, library talks, school visits and writing workshops.

For many writers, the prospect of keeping 150 teenagers entertained for an hour, or running a workshop to suit 30 or more primary pupils of different abilities, is a scary prospect. But it’s true what they say: the more you do it, the easier and the more enjoyable and rewarding it becomes. For me, the best part is coming away from a school feeling that perhaps, just perhaps, I’ve inspired at least one person in the audience to try a genre that they would normally pass over.

You see, the books that I write fall into the category of historical fiction, and I have come to realise that it’s a label that’s not always attractive to young readers. When visiting schools, I often begin my talks by asking the audience to imagine that I have given each of them a crisp £10 note to spend in their local bookshop. I then ask how many of them would automatically gravitate towards a historical fiction novel. Usually I’m lucky if I get four or five hands in the air. But here’s the rewarding part. If I ask the same question at the end of my session, the response tends to be quite different and is reinforced by an enthusiastic queue at my book signing table.

Young people tell me that they fear historical fiction novels will be dull, turgid and irrelevant. They think of the classic novels that they have to read, review and analyse endlessly in class; books that they recognise are well-written but which are forced upon them and will always carry an association with dreaded exams. They certainly don’t expect historical fiction to offer excitement, adventure, romance, horror, mystery or magic.

The challenge is to show them that historical fiction can be all of those things, that it’s not all about stuffy old parlours, corsets and tight-lipped ladies sipping tea. A historical fiction novel can be just as thrilling and every bit as gripping as the next book on the shelf, because history is a source of so many great stories – amazing adventures, spell-binding mysteries, powerful tragedies and romances. And as writers, we can make those true stories even better than they were in real life.

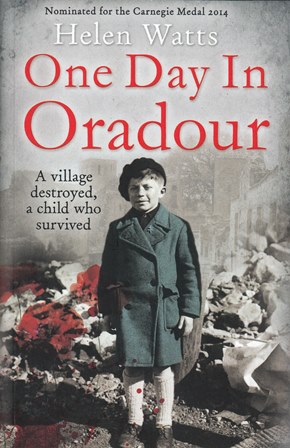

But how can we entice young people to pick up our books in the first place? To me, the key is in finding something to surprise them: spotting a true story that arouses their curiosity and leaves them wondering why they’ve never heard of it before. My novel One Day In Oradour, for instance, was inspired by a Second World War event: the massacre of 644 innocent men, women and children in a small French village one day in 1944. It was a compelling, moving, shocking true story, not without its fair share of controversy, yet it was relatively unknown outside France. A surprising choice of story for a young audience, yes, but among the tiny group of survivors from the massacre was a seven-year-old boy who was the only one of his schoolmates who had the courage to try to escape. He even played dead when shot at by a young SS soldier and lay in a field for more than two hours, not daring to move while his home was razed to the ground.

This brave boy’s story was a way in: a way to make a 70-year-old event meaningful and relevant to a modern-day, young audience. But once hooked, would my readers stay with me? How would they react to a story about such a horrific loss of life? Would they not demand a happy ending? It would have been all too easy to shy away from revealing the true extent of the SS soldiers’ cruelty. It might have been less risky too, to leave out some of the more gruesome details. But I believed that to do either of those two things would be to do a disservice not only to those who lost their lives or lost loved ones that day, but also to the reader. For this was a story that opened our eyes to the extremes of human behaviour. It held up a mirror to a world in which, side by side, there could exist a character like Gustav Dietrich, who was willing to order the mass slaughter of hundreds of innocent people, and a small boy like Alfred Fournier, who had the courage and sheer determination to survive against all odds while his world was turned upside down around him.

I have had an amazingly positive reaction to One Day In Oradour, perhaps the most moving being the teenage student who came up to me at the Southern Schools Book Awards to tell me that this was the only book she had ever read right through to the end. So there’s the proof: when given a chance, historical fiction can be as big a hit with young readers as any other novel. And you only need to look at the success of titles like The Boy in the Striped Pyjamas and The Book Thief or the popularity of writers like Michael Morpurgo, Berlie Doherty and William Sutcliffe, for further evidence.

So this is a plea to all historical fiction writers. Ignore those doubters who suggest that our genre is not commercial or mass-market enough, to appeal to today’s young readers. Just keep searching for those magical sparks, those stories and tales from our past that when rekindled and retold will fire our readers’ imaginations and show them that historical fiction isn’t history, it’s way, way better than that.

Helen Watts is the author of the award-winning and Carnegie nominated One Day In Oradour (Bloomsbury/A&C Black, May 2013). Her latest novel, No Stone Unturned (Bloomsbury/ACB Originals, Sept 2014) has been shortlisted for The Historical Association Young Quills Award. For more information about Helen, her books and her author talks and workshops, visit her website.

Comments