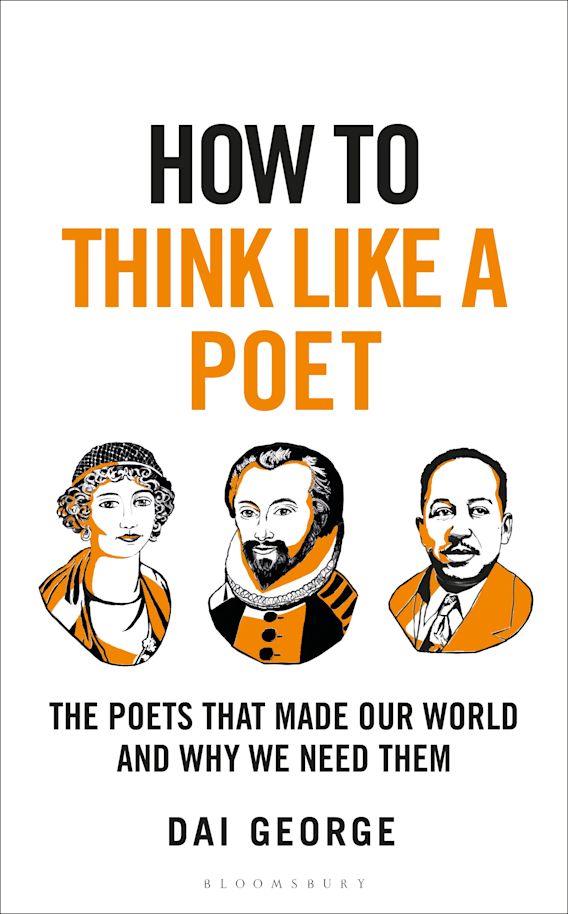

In this exclusive extract from How to Think Like a Poet, novelist and poet Dai George discusses contemporary poetry and the set ideas people have around what a poem should or shouldn't be.

As a creative writing teacher, I’m used to students coming to class with set ideas about poetry – what it is, what it should be. Many of those ideas have roots buried deep in history. That it has to rhyme is the big one, though nowadays most people are wise to my agenda when I broach the topic. (‘No, Dai, it doesn’t have to rhyme,’ they concede. ‘It’s just nice if it does!’) Good modern poetry can rhyme, of course,as anyone who’s read A. E. Stallings or Paul Muldoon will confirm, though usually it doesn’t. It tends to be written in the loose, endlessly adaptable mode that we still call ‘free verse’, for want of a better term. Alas, that label essentially describes everything and nothing in an era when a very high percentage of poetry is ‘free’, in the sense that it steers clear of rhyme, meter and set forms. It would be quicker to count the people who still go in for iambic pentameter than those who don’t.

We need to remind ourselves that this is a pretty big change from the historical norm. Free verse (or ‘vers libre’) originally sprang up as a necessary term to describe a radical minority of French writers around the 1880s: poets like Jules Laforgue who, in his Derniers vers (Last Verses), chucked the rule book out the window and composed without constraints. Spreading to English-language poetry through the modernists – Pound, Eliot, H.D., Wallace Stevens – it quickly became standard practice. So familiar was free verse by the 1930s that Robert Frost could quip that he’d rather play tennis with the net down than write in that style. It’s a good analogy, witty and to the point, though of course it loads the dice by suggesting that poetry can only be fun and rewarding if we abide by the rules. That works for sport, but I’m not sure it’s true at all when it comes to literature. In fact, one could say that the history of modern poetry is a history of people learning to live, feel and write in a universe without any rules.

Nevertheless, teaching creative writing I sometimes feel like a tennis coach trying to enthuse people about the virtues of playing without a net. They’ve turned up fully prepared, sweatbands on their foreheads, racquets at the ready, and the first thing I get them to do is rally back and forth on an empty court. To keep our spirits up, I point to something lovely that Carl Sandburg once said in response to Frost (‘I have not only played tennis without a net but have used the stars for tennis balls’). At first this goes down well, until we try to play a game in the Sandburg spirit and realize that we don’t have any stars. Metaphors are tricky like that, and they often seem to be the only thing that poets have to hand.

I exaggerate a little. (Only joking – I exaggerate a lot. Come do a class with me! It’ll be fun.) But the substantial point remains that poetry in the twenty-first century is a strange – and I think very wonderful – form of creativity without rules. It can be this, it can be that, but it’s more likely to be something else. If the person who wrote it calls it a poem, then it’s a poem.

Comments