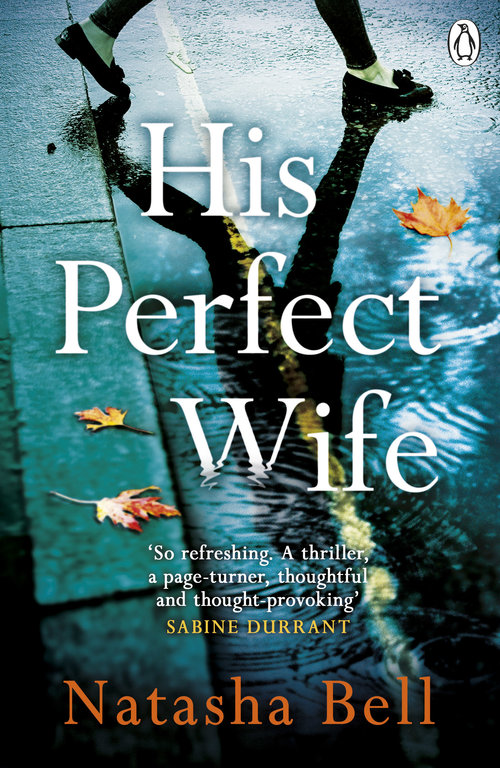

Natasha Bell, author of psychological thriller His Perfect Wife, offers some tips on how to structure a novel with multiple timelines...

The nicest piece of feedback I’ve had on my debut novel – the one that made me dance around my desk and feel like I’d got a big gold star from my favourite teacher – was from my copy-editor, Sarah. She emailed to say His Perfect Wife was “extremely polished for a first novel”, that the complex structure “hangs together beautifully” and added “it’s unusual for authors not to slip up somewhere on the timeline!”

The reason this made me so happy is that Sarah is perhaps the only reader I’ll have to notice this and to understand and acknowledge the time, effort and torn-out hair that went in to working out that time line and structure.

Which is how it should be.

If you’ve done your job well, then your reader shouldn’t notice the structural acrobatics you’re performing. Like a model walking the catwalk in six-inch heels with just-woken-up hair or an Olympic skater pulling off the perfect quadruple jump, your structure should look effortless. Even if the truth is it’s had you lying awake at three am and crumpling page after page of abandoned notes as you’ve fallen into a complex space-time wormhole that’s left you questioning your own existence.

But how? Here’s some tips:

- Plan. Even if you’re not a planner in the drafting stage, if you’re writing a book with multiple timelines, at some point you’re going to need to pull out a piece of paper and draw a diagram. For some writers this will be a fun activity where they get to think spatially rather than linguistically. For others, it will bring out the cold sweats. I start on paper, drawing messy timelines with too many annotations and then either switch to Post-Its on the wall or a spreadsheet. Dividing each of your timelines into a list of separate scenes and then putting them into any kind of format where you can move them around easily is the aim. Colour coding helps enormously.

- Experiment with structure. This is time-consuming and often disheartening, but utterly essential. If you have two or more time-lines then you have to decide how they slot together. Do you want to interlink them using alternating chapters (ABABAB)? Do you want to divide them into parts (Part 1: A, Part 2: B, Part 3: C)? Do you want to tease us with a bit of B before launching into the whole of A and then returning to B at the end? There’s no one-size-fits-all and you may have to try and try again, but there will be a structure that fits your narrative and you will know it when you find it.

- The linear question. There’s something that tempts us as writers towards non-linear narratives. We love to tell a story backwards or out of order. Perhaps it makes us feel clever, or entertains us even though we’ve grown used to the story we’re telling. The truth is, for readers, linear narratives are almost always easier to follow and more satisfying to read. Which is not to say we should never use non-linear structures, but we need a good reason. In All the Birds Singing, Evie Wyld deftly intertwines her two timelines by telling Jake’s present narrative in a normal linear fashion and her past narrative backwards. By moving from adulthood to childhood in the past narrative, Wyld answers the questions her readers find themselves asking in the present narrative, so each timeline compliments the other in both content and structure.

- Look for thematic links. The temptation with multiple timelines is to get too focused on how each one works separately, but at some point you’ll need to consider them as a whole. If you’re using alternating chapters, then you need to constantly be asking yourself why this chapter comes after that one and what it’s setting up for the next. This is where a spreadsheet comes in handy. If you plot each timeline in a different column, then what do you see when you look along the rows? Your structure must work horizontally as well as vertically.

- Don’t think you can get away with it. Even if you get it past your agent, your editor and your copy-editor, if you can see a plot hole then I guarantee you that at some point someone else will see it too. So sort it out.

Natasha grew up in Somerset and studied English literature at the University of York. She holds an MA in the humanities from the University of Chicago and an MA in creative writing from Goldsmiths. She lives and works in southeast London. Visit Natasha's website.

Comments