When I write about climbing, I am fascinated by the place it happens in, and the stories of the people.

But it would be pointless to pretend that you could write about climbing, without including the action of rock-climbing. I have read many action-packed accounts - and not just of rock-climbing- which have been jargon-laden, incomprehensible, probably made up, jammed in for no good reason, tediously detailed, or too long. Here are my tips for on writing real-life action.

Warm Up.

Action scenes in writing need to make sense. I don’t start climbing without uncoiling rope, putting tiny shoes on and checking I’ve got everything I need. There is usually a huge amount of preparation in setting out, and it should be the same for writing about it. The reader wants to know why I’m doing this, what the risks are, what the rewards are, and why they have to care. No one ends up having a fight, dodging a car, having sex or picking a lock without there being a reason for it.

Get experience.

Not all writing has to be from personal experience, otherwise we would have no fantasy, no historical fiction, nothing but autobiography. Some experiences are hard to come by, potentially because they are entirely imaginary. But even the most extreme of imaginary action - flying a dragon or diving through a black hole - can have touching points of experience that we can share and that people can recognise.

Writers do this anyway, drawing on personal experience of grief or love to make characters vivid. Framing some physical experience will give the reader insight and the prose will stand out when you write it. I am not a top-climber and never will be, but I know what it feels like to climb at all, so hopefully I carry my readers with me when I put it on paper. Riding a horse or handling a snake will help with riding a dragon. Taking a corner too fast and oversteering into a skid will provide valuable insights into travelling through a black hole.

Get creative about what experiences you seek out: you might be amazed at what you can pay to do as experience-tourism, what clubs exist and what people do for hobbies. The more you put into it the better: depth of experience will show, but some is better than none.

Explain your jargon away.

Jargon is only useful to those already know it and a Glossary is a pain to flick back to. A jargon- word is a convenient label for something specific and often complex with layers of meaning. That is a gift for a writer. Find a way to explain away the jargon, and you often end up with something a bit good.

For me, a ‘crimp’ (a small and specific type of climbing handhold), might become ‘the riffled edge of a deck of cards that I could barely get a full fingertip onto’. More words, but maybe a better image that might stick in someone’s head.

Steal with honour.

When you’re writing about what someone else has done, don’t forget to credit whatever sources you use. Don’t just rewrite it either, passages like that are flat and list-like. Given that you have acquired a touching point of your own experience (see above), put in some interpretation of the events. That way you are acting as a bridge of understanding between your subject and the reader.

I had huge doubts about my ‘right’ to do this (not legally speaking), and that I wasn’t as good a climber as the people I was writing about. But in several interviews, top climbers made the point that the emotions experienced by people across climbs are universal, it was only the technical difficulty that changed. My fear climbing something easy was the same as theirs on something far harder.

Put emotion into the action.

Falling off a climb was never about the risk of injury, I -generally- climb in a very safe style. Falling off , and ‘failing’ on a route are much more loaded with feelings of shame and humility for me. The fear I have felt on stuff right at, or beyond my grade, has been totally disproportionate to the consequences. Without the emotional aspects of action and the intensity of the experience, the whole thing would be just doing pull-ups in an interesting setting.

Don’t be boring.

Rock climbing, the test of an individual’s ability against immutable forces of gravity, is fascinating. Talking about it is not. I’ve seen enough glazed expressions to know it is easy to lose an audience, and that is talking face to face with friends.

One of the first people to read the fragment of work that would eventually become my first book commented “you seem to have an instinct for when the reader is about to lose interest”. Actually I didn’t. One of my friends who read my work was just unafraid to comment ‘Getting Boring Now, Pete’, so I’d change the subject.

Constant action gets wearing and dull. Change the pace, let us get our breath back and do some stretches. A typical climbing trip - without weather wrecking everything- is probably 30% driving, 30% hanging out with mates, 30% walking around, 5% eating snacks, 3% faffing with rope, 1% actual climbing and 1% watching someone else climb.

Thems the rules, now go and write a book.

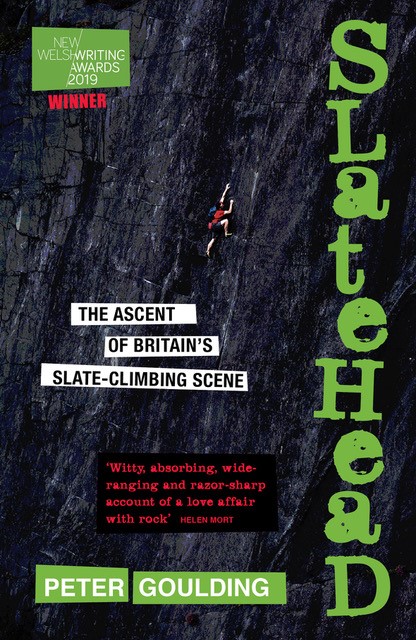

Peter Goulding is a climber from the north of England. He has spent most of his working life in pubs, kitchens and on building sites. He currently works at Center Parcs as an instructor and is an alumnus of UEA. Slatehead: The Ascent of Britain's Slate-climbing Scene was published by New Welsh Review under the New Welsh Rarebyte imprint on 4th June 2020 in e-book format for £9.99, and in paperback format on 29th October 20202. You can follow Peter on Twitter over at @flatlandclimber.

Comments