For those who don’t already know, can you tell us a little about your latest projects - the book launch of Not Another Happy Ending and any others you may be working on?

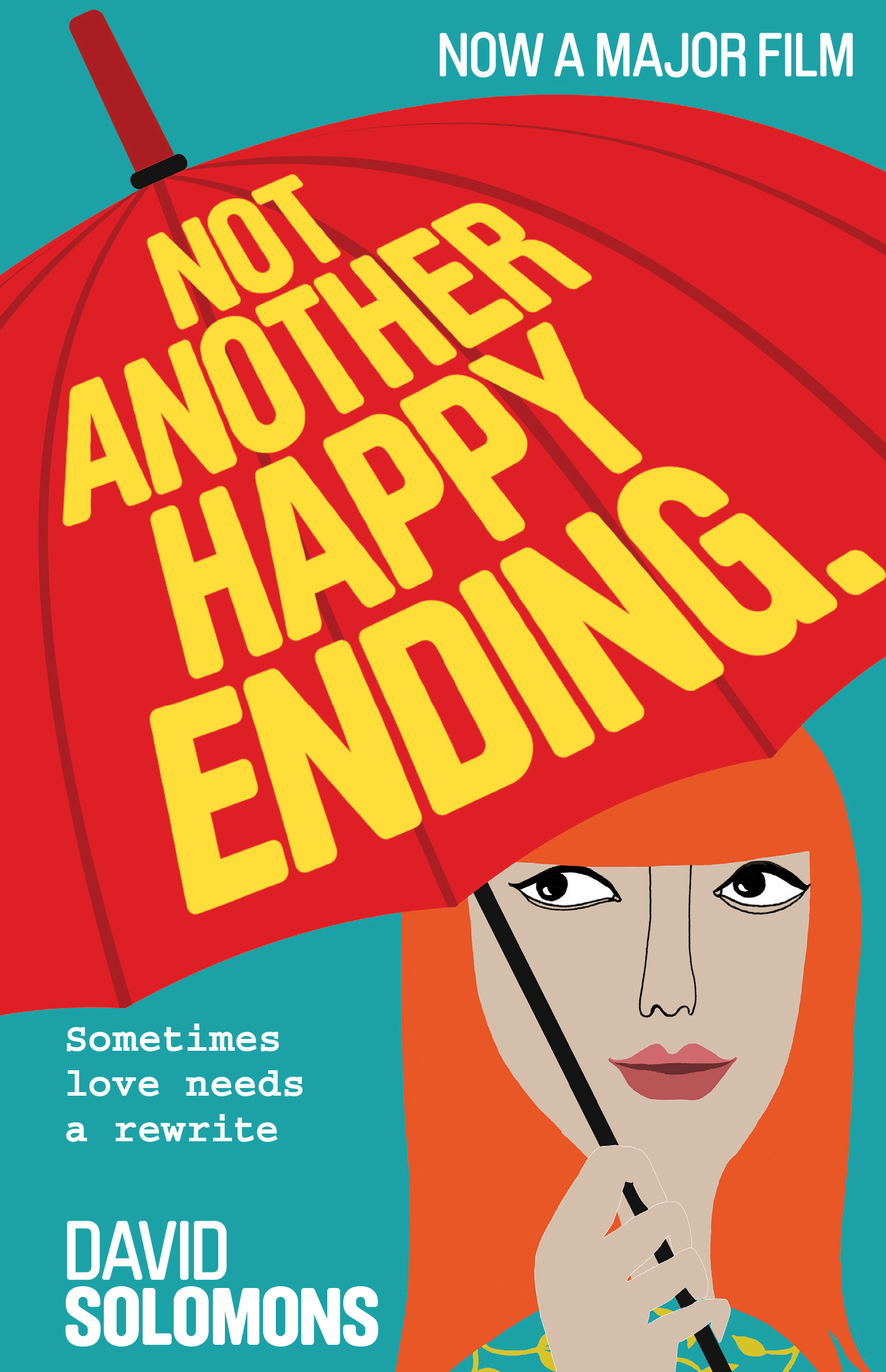

Not Another Happy Ending is the novel of the film of the same name, both of which I wrote. Someone recently referred to the novel as ‘the writer’s cut’. It’s a story about writer’s block and whether you need to be miserable to be creative. Also, an unashamed rom-com.

I’m currently working on a new novel, which I’m writing for my son, Luke. He’s fourteen months old, so I reckon I’ve given myself plenty of time to finish it before he starts bugging me to read. I’m also co-writing a feature film screenplay with my wife (and New York Times bestselling author), Natasha Solomons. We’ve collaborated on several projects, including an adaptation of her debut novel, Mr Rosenblum’s List. So much bickering, so little time.

You’ve adapted your latest film to become a book. What inspired you to do this?

I was tricked into writing the novel by a devious lit agent. Said agent convinced me that since I had already written the screenplay, the novel would be a breeze. He lied.

Have you always wanted to write a book? Why now?

This is my second novel, but the first to make it across the finish line. The first one lies dustily in the bottom drawer, an overlooked masterpiece, of course. So yes, I’ve always been a frustrated novelist and after the disappointment of my first foray the prospect of sitting down to turn out another one was not immediately enticing. But writers will understand – you don’t have a choice. You find yourself showing up at your desk every day and somehow the pages fill up. I imagined, naively, that getting this novel published would be a simpler matter, because of the film. Everyone in publishing talks about ‘platform,’ i.e. a selling hook that helps your book emerge from the background noise. Well I’m not a celeb, but I did come with a here’s-one-I- made-earlier feature film. I had sizzle to sell the sausage. I’m sure it did help the decision-makers in the end, but what’s pleased me most has been the enthusiastic reaction to the novel, not as a tie-in, but as a work in itself.

As an award-winning screen-writer, what would you say has been the highlight of your career so far?

I contrived to miss the highlight of my career, which came earlier this year when Not Another Happy Ending the film was chosen to close the Edinburgh Film Festival. While everyone else associated with the production walked the red carpet I was in a hospital bed. There was morphine, so I didn’t miss out entirely.

Film-to-book adaptations aren’t always favourably received. Was this something that played on your mind when you started writing?

I think there’s an idea that tie-ins are knocked off in a lunch-break with no thought to literary merit, their only purpose to make a quick buck. Well, to that I say, if only. I simply wasn’t ready to relinquish these characters and this story. I had plenty more to say. A novel seemed like a good idea at the time.

You’ve also adapted a book (Five Children & It) for the screen: what was different about this process? Did you find it easier or harder?

Five Children & It was a great experience, especially for a lifelong Muppets fan. Apart from anything else I got to hang out at the much loved and sadly missed Creature Shop in Camden. Walking through that ordinary looking front door was the real world equivalent of entering Narnia through the back of a wardrobe.

Anyway, the Henson Company had read a spec screenplay of mine and asked me to adapt the E. Nesbit novel. The brief was simple. They liked certain elements of the novel and wanted to see them in the screenplay, but gave me free reign to invent the rest. Which I did. Purists, look away now. For instance, early on in the process I came up with a sequence where the children make a wish that effectively clones them. The director, John Stephenson, liked that idea for a reason I could never have foreseen: technically, it was a visual effect he could pull off really well within the budgetary constraints. He was right. I still think it’s the most successful single moment in the film.

Did I take liberties with the source? I would argue that the novel is not one of E Nesbit’s that comes under the heading of ‘beloved’. If I’d been asked to adapt The Railway Children, I’m sure I would have taken a more reverential approach. The funny thing is the number of people who tell me how much the film took them back to when they were youngsters reading the book, even though the differences are substantial.

When adapting a book for the screen, you obviously can’t include every small thing that’s in the book. How do you decide what to cut out whilst making sure you aren’t losing any of the important elements of the story?

In my experience the first draft is always the most faithful to the book. The ground starts to shift after that. What’s the filmmaker’s goal? That’s the question you have to ask. And the answer is to make the best film from the material. Nobody wants to sit in a movie theatre and watch a flick-book. Even ardent fans of a novel want a film experience. And the two are distinct. So, for me adaptation is about capturing the spirit of the source material. When you are invited to pitch for an adaptation the production company will ask for your ‘take’. As a writer, that’s the interesting part. The film adaptation should be regarded as a creative response to the novel, not an attempt to transcribe every word.

As both a screenwriter and now an author, what do you feel are the differences and similarities between the two mediums?

A few differences first. A film is ultimately a collaboration involving many people, while as the author of a novel you get to write, direct, even light the whole thing yourself. Also, I haven’t heard of a novelist being fired from his own book. When writing a novel you don’t have to worry about the budget. A favourite scene in a novel won’t be cut because the running time is getting on the long side. Digression works in a novel but rarely in film. William Goldman’s film-writing rule about coming in as late as possible to a scene and leaving as early as possible can be relaxed in a novel.

Similarities. I was relieved to discover that both require essentially the same imaginative process, in which you’re summoning up characters in a set of circumstances, trying to get into their heads. And in both you’re imagining a reader or viewer and how he or she will feel when they observe these characters behaving in this way.

What would your advice be for writers trying to make the transition between the two?

I know of a few screenwriters who have turned to long-form and in those cases I think they’ve been motivated by rejection. Even after a screenplay or a treatment that they were confident should be produced was repeatedly turned down, the voice in their head said this is good work, stick with it. Turning that impulse into a novel is hardly the easy option, but when it works the satisfaction is enormous.

If you’re a novelist who wants to write a screenplay (based on your own novel) I think you’re in a good position. When I first started out I met with an agent who told me that the smartest way to get into screenwriting was to write a novel first. I didn’t understand at the time, but now I get it. Producers want material. When it comes to making a deal you’re in a much stronger position when you’re the rights holder and not simply a writer for hire. So own your material, that’s my advice. And novelists, be aware that you’ve had it easy to this point. Publishers tend to be nice to their writers. The filmmaking process can get brutal.

In a novel, it can be much easier to tell how the protagonist is feeling, as we’re given an insight into their thoughts – how can you do this when writing a script? How do you make sure the emotions you want to convey are successfully shown on screen?

I think film’s greatest power is its ability to move us. But of course two of the key tools to achieve this – performance and music – aren’t present in the screenplay. So, what do you do to convey the inner life?

Orchestrate the silences. Ideally, you will have done enough work in the preceding scenes that coming in to a crucial confrontation it’s more about what is left unsaid.

Don’t forget about actions. How does your character pour his coffee? Get into his car? These things are indicators of emotional state.

Of course there’s voice-over, a device that goes in and out of favour, which can give access to the thoughts and feelings of your character. If you do use it make sure it’s not simply describing what the audience can already see on screen. The best voice-overs come in at an angle.

Your character can confide in another, or what I like to call the ‘We used to come here all the time… before the accident’ approach. It’s an indicator in the dialogue of her state of mind that informs the scene that follows.

You can use weather to express an emotion - the so-called pathetic fallacy associated with the Romantics. The same scene in bright sunshine or pouring rain carries different emotions. In Not Another Happy Ending, I had written a lot of scenes that were meant to happen in the rain, but in the end the shoot happened in glorious sunshine and the budget didn’t allow for too many fake rainstorms. The DoP was delighted and the film glows as a result.

Foreshadowing is another device. Set up something small but significant (a refrain, an object – rosebud, I’m looking at you) early on in the screenplay and by careful repetition it acquires a significance that can unlock the emotion in a climactic scene.

But be careful with subtlety, especially in the early drafts. One thing screenplays are not good at is containing ambiguity, and I don’t mean the ‘is he the killer or isn’t he?’ genre. You find that during development what executives and producers want is to clearly see the through-line of the story. In emotional terms that means they ask questions such as: what is the main character feeling going into this scene, and then coming out of the same scene? Is there a change of emotion and is it clearly marked? As the writer you walk a fine line, one which you’ll fall either side of during every development process. Expect to hear the phrases ‘well, it’s not clear on the page’ and ‘it’s too on the nose,’ usually during the same meeting.

Finally, even if you do manage to convey brilliantly that a character in the midst of an epic space battle is also thinking of her childhood pet hamster who died in a tragic wheel accident, the actor playing the part will more than likely take the same line and bring something unexpected to it – and that’s when the filmmaking process gets interesting.

Finally, what are your tips for aspiring screenwriters?

- Don’t be a screenwriter, be a hyphenate. Writer-Directors are king.

- Write fast. Rewrite slowly. You will have ten to twelve weeks to turn in a first draft and usually half that for the revisions, which is backward. First drafts are the fun part; rewriting is painstaking.

- Notes are a fact of life. When a note strikes you as being utterly moronic, don’t dismiss it out of hand. It’s often pointing at something elsewhere in your screenplay that isn’t working. Take a deep breath, retrace your steps until you find it. A-a-a-nd sometimes it is just a moronic note.

- Write one thing well. Maybe you like thrillers as much as musicals, but at the start of your career then make things simple for people. Be the thriller guy. Or the musical guy. Not both. Once you’re established (so they tell me) you can diversify.

- You will grow old waiting for a film to get made, so have another job, preferably part-time that gives you time to write whilst paying you enough to live on. I worked as an advertising copywriter for many years, writing my scripts in the margins of the day.

- Find a producer who’s as hungry as you are and preferably a rung or two further up the ladder, and team up.

- If you take a meeting at Disney’s animation building, give yourself more time to find a guest parking spot than you can possibly imagine.

David Solomons' debut novel, Not Another Happy Ending, is available in e-book form here.

Comments