In the latest in our series of interviews with self-published authors, we talk to military science-fiction writer and bestselling Amazon author Marko Kloos.

For those who are unfamiliar, can you tell us about your book?

Terms of Enlistment is a military science fiction novel. The protagonist, Andrew Grayson, is a kid from the welfare slums of Earth, which has a slight overpopulation problem in the 22nd century. Andrew is tired of eating reconstituted soy and being stacked in dole housing, and he decides to apply for military service, which is one of the few ways out of the Public Residence Clusters. He wants to get off Earth and go into space but, as he finds out, in the military things don’t often go your way once you’ve signed that enlistment contract.

When did the idea for Terms of Enlistment first occur to you?

I wrote the first few chapters as my application piece for the Viable Paradise SF/F Writers’ Workshop, which is held every year on Martha’s Vineyard off the coast of Massachusetts. I wanted to write a genre staple, Young Man Goes To Boot Camp And Then Off To War, but I wanted to make my version just a little different. What if the military got a hundred applicants for every boot camp spot, and could afford to be highly selective as a result? What would boot camp look like if the instructors didn’t care whether you made it through or washed out?

I also wanted to sprinkle in some of the experiences of my own military service (I served in the German military as a non-commissioned officer), and the military SF genre seemed like a fun playground for that.

When did you find the time to write?

I wrote Terms of Enlistment and its sequel while being the stay-at-home parent to two small children. I had to write early in the morning before everyone got up, or in the evening after everyone went to bed. I also got in quite a few pages sitting on benches in playgrounds while the kids played. Being a full-time parent is great for writing discipline--you learn to carve your writing time out of the day whenever you can. That means cutting out a lot of the stuff that’s not as important to you as finishing a novel, of course. I didn’t spend very much time in front of the TV, and my World of Warcraft characters sat around in inns and got fat and lazy.

You write mainly science fiction and fantasy – who has influenced you in your writing? Was there a particular book or film that inspired Terms of Enlistment?

The obvious answer would be Robert Heinlein, but that’s only partially true. I’ve always been a fan of military adventure from a soldier’s perspective--a prime example would be James Cameron’s Aliens. I wanted to throw a bunch of grunts into extraordinary circumstances and write about the way they deal with them without making the military veterans in the audience go, “Oh, come on!”

I also wanted to throw in a bit of social commentary without being preachy about it. Joe Haldeman’s Forever War was a good yardstick for that. Heinlein’s Starship Troopers, as good a read and as seminal a genre influence it is, really whacks the reader over the head with the politics stick, and I wanted to avoid that kind of approach. A twenty-year-old kid from the projects wouldn’t care much about civil rights and social policies--he’d care about getting real food to eat and having the opportunity to get out of the concrete gerbil mazes of the PRCs. The social conscience and the moral compass tend to only kick in once the belly is full and the roof over your head doesn’t leak dirty rainwater on you while you sleep.

Can you tell us anything about the sequel, Lines of Departure?

Lines of Departure takes place five years after the events in Terms of Enlistment. Andrew has matured a bit since he left the PRC with an induction letter in his hand. He is half a decade into a dangerous military career on the sharp tip of the spear, and things aren’t going so well for Team Humanity, both on the overcrowded Earth and out in the colonies past the Thirty, the 30-lightyear sphere around Earth that marks the boundary between the Inner and Outer Colonies.

Yet despite being at war constantly for half a decade, Andrew and his girlfriend, drop ship pilot Halley, still try to do what young people do regardless of the circumstances--have a relationship with one another, even if it only takes place on leaves that are spent mostly in Fleet recreation centers light years away from Earth.

Why did you choose to self-publish? Did you try the traditional route first?

I finished the manuscript for Terms of Enlistment in 2009 and immediately sent it to an editor who had previously requested the completed work. As far as I know, it’s still sitting somewhere in his office, in a box marked PRIORITY MAIL. (The postage was almost as cheap as First Class mail, and they do let you use that nifty free box.)

I also submitted queries to just about every literary agency in the book, and I sent submissions to most of the major SF/F publishing houses in the country. I got two or three requests for partials, and that was pretty much it.

Until recently, I was firmly against self-publishing and fully intended to go the traditional publishing route exclusively. My reasoning was that most self-published books don’t make a whole lot of money for their writers, and that I would need the distribution and marketing acumen of a major publishing house to ever make more than beer money with the novel.

The breaking point came a few months ago. I noticed a call for military SF submissions from an agent on Twitter. I remember getting out of bed again to go downstairs to the computer to look up her submission guidelines and send her a query. It was short, professional, and exactly following the guidelines.

The next morning, I had a form rejection in my Inbox. She had rejected the query without even asking for a partial--without having read a single sentence of the novel.

I said a very naughty word at the screen. Then I realized that I really didn’t have very many more places to send the manuscript, and that it would remain a trunk novel if I didn’t get it out in front of readers myself. So I activated a Kindle Direct Publishing account, formatted the novel for the Kindle, bought some stock art and made a cover, and uploaded everything to the Kindle Store. I think it was live and available for purchase eight hours after I had received that last rejection.

Would you have taken the opportunity to go down the traditional route if that had been a possibility?

I would have been delighted to sign a publishing contract if someone had offered it. I did, in fact, end up going the traditional route after three months of self-publishing. Terms of Enlistment did exceptionally well on the Kindle store--not just for a self-published novel, but for a novel, period. (At one point in April, it climbed all the way up to #2 on Amazon’s SF bestseller list--not just Kindle books, but all Science Fiction, print and audio as well as ebooks. Alas, I didn’t make it past Stephenie Meyer, for which I will nurture a LIFE-LONG GRUDGE.) All of a sudden, I started getting approached by agents interested in the novel. I ended up signing with an agent who ended up getting me a traditional two-book deal about two weeks after I signed with him.

What do you think the greatest advantage of self-publishing is?

For me, it’s the control. With KDP, I am able to track my sales in real-time, so there’s no guesswork about how your novel is doing.

Amazon also pays royalties monthly rather than twice a year like most publishers, and you’ll know exactly how much will be coming in because the royalty statements are also updated on a weekly basis.

Then there’s the royalty model--I get to keep 70% of the sales price versus maybe 15% ebook royalties from a traditional publisher. (Of course, KDP books won’t make it into brick & mortar bookstores, which still account for most book sales, so there are disadvantages too.)

Overall, however, I like the transparency and control I have with self-publishing. Yes, I have to be my own accountant and marketing department, but I’m never in the dark about when and how much I’ll get paid.

On the other hand, is there anything you feel self-published authors may miss out on? Such as the editor-author relationship.

I think the main thing that self-published authors may miss out on is a sense of outside perspective as far as writing quality and marketability is concerned. Your editor is there to make sure your novel is the best it can be. With the immediacy and instant gratification of self-publishing, you can finish a draft on Friday morning and have it up on Amazon by lunch, and from the amount of mediocre (and downright terrible) self-published stuff on the Kindle store, I suspect that a lot of self-published writers put their stuff out without getting a skilled second pair of eyeballs to look at it.

How, if at all, has having an agent been of benefit to you?

Getting an agent was the single best thing that has come out of my self-publishing venture. I signed with Evan Gregory of the Ethan Ellenberg Literary Agency, who got me a two-book deal with 47North. He knows the business, and we discussed every aspect of the contract offer before I made the decision to sign. I really came away from the whole deal with the feeling that Evan is concerned with what’s best for my career, not necessarily what generates the bigger agency fee. It’s a big relief to have someone in my corner who knows the business so I don’t have to spend my writing time going through contracts and negotiating terms. I can focus on writing, because he takes care of finding a place for my stuff and making sure the contracts are fair and favorable.

You have a blog and a website – how important do you feel interacting with your fans has been?

I feel that having an established reader base had a lot to do with the success of my self-publishing experiment. I’ve built a modest audience over about ten years of blogging, and a lot of my readers were familiar with my writing because I have been posting free stories and essays over the years. When I finally decided to bring the novel out myself, I had a built-in audience that helped the book get its initial sales push.

Interacting with readers is a great way to get validation and feedback. I’ve had readers alert me to typos I had overlooked, I keep getting comments from people who enjoyed the novel, and the whole give-and-take via blog and social media makes me very aware of the fact that I am writing for an appreciative audience, not just for a paycheck or a personal sense of accomplishment. In a way, writing is every bit a performance art as acting or singing, and online interaction brings us closer to the readers than just answering fan mail and doing book signings every once in a while.

Do you feel there is more of a sense of community with self-publishing than there is with traditional publishing?

I have found the opposite to be true. For me, there’s more of a sense of community in the traditional publishing scene. I have a few home turf conventions I attend every year, and one tends to see the same faces because our genre is fairly small and familial. I made twenty-four new friends at Viable Paradise, the first writing workshop I ever attended, and every time we get back together, it’s like a family reunion.

I’m not saying that the self-publishing scene doesn’t have the same sense of community, but self-pubbing congregations--whether online or in the real world--tend to be more about self-promotion and sharing or gaining tips & tricks for selling books. A lot of self-published authors confuse “community” with “potential audience/customer base for my work”, and that’s always awkward at best - and downright repellant at worst.

How important is marketing yourself in the early stages of your self-publishing career? Any tips?

Self-marketing is a tricky thing. Your biggest problem as a self-pubber is obscurity--nobody knows you exist. But self-promotion is incredibly toxic to social interaction in large doses. I have a strong aversion to pushing my own work on social media. I see Facebook and Twitter as a way to keep in touch with friends, and I try to be entertaining by posting fun updates. People can smell when you’re not genuine, and when you use social media mostly for self-promotion, you use your followers as a means to an end. That kind of thing gets you unfollowed and unfriended faster than anything else. Announcing the availability of your novel on your blog is totally fine and may help you get sales if your readers like your other writing already. Spamming Amazon links five times a day on Twitter or Facebook isn’t fine. It annoys people and makes them not want to read your stuff. Self-promotion is best used in very small doses, and ideally packaged with humor or personal relevance.

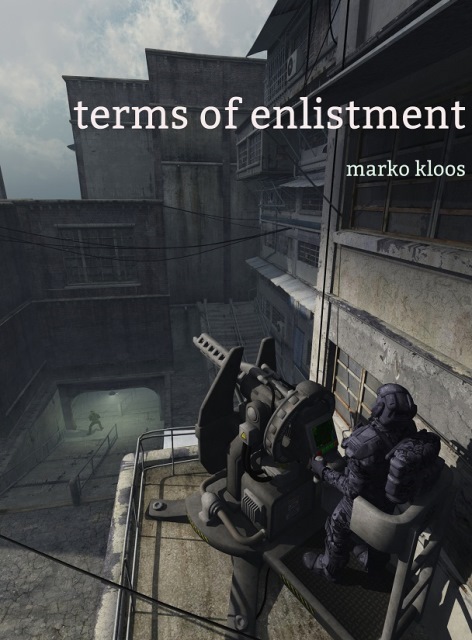

Did you design your own cover? How important do you think cover design is to a potential reader?

I did design the cover for Terms of Enlistment. I purchased some stock art I liked, and worked it over in Photoshop for a little while to put a title and byline on it that matched the colour scheme I wanted. I have gotten very positive comments on it, but I also know that some people hated the cover and almost didn’t pick up the book because of it. (Hooray for Amazon’s “Try a sample before you buy” Kindle option.)

The cover is what catches a reader’s eye, and if it looks amateurish, it’s a huge strike against the book. Self-published novels already have to overcome a reputation of half-baked amateurism (which is sadly deserved for a great number of self-pubbed Kindle titles--there’s a lot of first draft material out there packaged as a novel), and the badly designed cover is pretty much a hallmark of the badly-written self-published novel.

Finally, do you have any advice for writers looking to self-publish?

Forget all the nonsense about a “personal brand” or any of those other marketing buzzwords out there. There’s no marketing trick that will guarantee you sales or a readership, and people don’t appreciate being used as a means to an end.

Write a good novel. Edit the hell out of it until it’s the best possible work you can produce. That’s the first and most important part of the process--if you don’t have anything written that’s good enough to interest, excite, and entertain, no social media sales strategy will help you.

If you do decide to go the self-publishing route, be aware that it’s all on you: marketing, ebook formatting, accounting, cover design, public relations. All of that takes away time from writing--a lot of time. Every hour you spend messing with cover art or fonts for your book cover is an hour you don’t get to spend writing.

Don’t expect sudden riches. The self-publishing success stories you hear are about as rare as lottery wins. Be glad for every sale you get, and be grateful for every bit of feedback readers give you. Don’t engage with critics of your work online--there will always be people who dislike your book, and there isn’t a thing you can do about it. And for God’s sake, don’t read Amazon reviews or check your Amazon ranking. (You will, of course, but don’t hold me responsible for your newly developed neurosis if you do.) Once it’s out in public, it’s out of your hands, and people have the right to love it or hate it.

Reviews and recommendations are worth their weight in gold. Word of mouth is how we find new writers to like.

Be very sparing with self-promotion. People can smell when others are trying to sell something, and pushing your own stuff excessively will make people tune you out or downright avoid you.

Above all, be glad your stuff finally has an audience, however small or big it may be. Not many people can say they’ve finished a novel, and fewer still can say that other people paid money to read it. Whatever your sale numbers, you’re better off than you were when that novel was sitting on your laptop’s hard drive. And don’t obsess over any of it - put it out there, let readers find it, and get to work on the next thing.

To find out more about Marko and purchase his books, take a look at his blog here and follow him on Twitter here.

Comments