As part of his series of articles for writersandartists.co.uk on his new Howdunnnit Machine, author Malcolm Pryce considers the employment of shamelessly effective writing tricks.

In previous posts on my Howdunnit Machine I have described the fictive dream as an altered state, a walled Garden of the Heart where we can round Cape Horn without getting wet. It follows from this that the writer’s main job is to keep the reader in the Garden. Now I will look at the techniques for doing this, and will incidentally shed light on a question preoccupying a lot of people these days, namely why so many people check their Facebook status during sex.

The first requirement is to make the Garden so nice the reader doesn’t want to leave. You have to fully imagine the dreamworld, but you don’t need to transmit all the material you have imagined. By some strange magic it will inform your writing anyway. But only if you have gone to the trouble of adequately visualising it first. (Actually, the magic is not so strange. If you are interested Google the concept of Exformation invented by Danish science writer Tor Nørretranders.)

Words are the paints but not just any words will do. The correct ones were identified a century or so ago by Sir Arthur Quiller Couch, a crusty old duffer who gave a series of lectures given at Cambridge called On the Art of Writing. This tract made a great impression on me when I was starting out and I commend it to anyone who wants to learn to write. It is available free online here. Quiller-Couch instructed us to use things we can ‘see and touch’. Concrete, tangible, simple Anglo Saxon nouns. The reason is simple. When you say dog, I instantly get a picture in my mind. When you say canine, I get no clear picture, I have to stop and translate.

Allied to this is the need to use specifying detail. This is the lifeblood of fiction. Instead of saying there were paintings above the mantelpiece, you specify. There was an oil painting by Stubbs showing a racehorse under a tree. Specify the tree too. If you say circus performer you require me to guess which one. If you specify clown I instantly have a picture in my mind.

The task at all times is to make the dream vivid, graphic and palpable. James Wood in his treatise How Fiction Works has a great section on something he called ‘Thisness’. This he defines as ‘any detail that draws abstraction to itself and seems to kill that abstraction with a puff of palpability.’ ‘Thisness’ makes prose sparkle. Examples he cites include the cow shit Ajax slips in at the Funerary Gems in the Iliad. Or the observation recorded by Orwell in his essay ‘A Hanging’, about the condemned man being led to the gallows who stepped aside to avoid a puddle.

Concrete nouns are judgement free. They don’t tell you what to think, they give you the information and allow you to form your own opinion. Rather than tell me the food was disgusting, which is an instruction to be disgusted, imagine you told me instead, the cook ran out of stock so she took the bandage off her foot and put it in the stew. Presumably this image arouses disgust naturally within you. This is really what we mean by ‘show not tell.’

The second main technique to keep the reader in the Garden is to use the time-honoured storytelling technique of curiosity. Scheherazade, the narrator of the Arabian Nights, is literature’s most celebrated exponent. As we all know, she told the Sultan a tale each night and got to the good bit just as dawn arrived, thus forestalling her doom for 1001 nights. A lot of new writers understand this but there is some confusion about the type of curiosity required. They often write with a certain coyness, withholding information in the mistaken belief that this will inveigle the reader into the text. But it doesn’t work that way, the aim is to intrigue but not mystify. To see the point, consider this famous opening line by Iain Banks:

‘It was the day my grandmother exploded.’

Told coyly, that would have been ‘It was the day something amazing happened to my grandmother.’

That is like an invitation to be amazed, whereas the original line actually amazes. I have a feeling the tendency to be evasive derives from the mistaken belief that to come out and say what is going on will let the cat out of the bag.

But you get far more dramatic bang for your buck by giving the game away. Once you read that grandmother line, your head crowds with questions and you spend page after page salivating at the prospect of the scene in which she gets blown up. Anticipation is more powerful than the actual event, as we all discovered as children at Christmas and have had confirmed by life ever since. Nothing ever quite delivers.

The reason for this is dopamine, which has been called the Kim Kardashian of neurotransmitters. (Because it’s sexy and always in the papers.) It is the key to your brain’s reward system but it gets secreted in anticipation of a treat, rather than the consummation. It’s like an itch that forever needs to be scratched. That’s why you keep checking Facebook during sex, just in case it might be better. If you are a lover, dopamine is a pest; if you are a writer, it is your friend. Just ask Scheherazade.

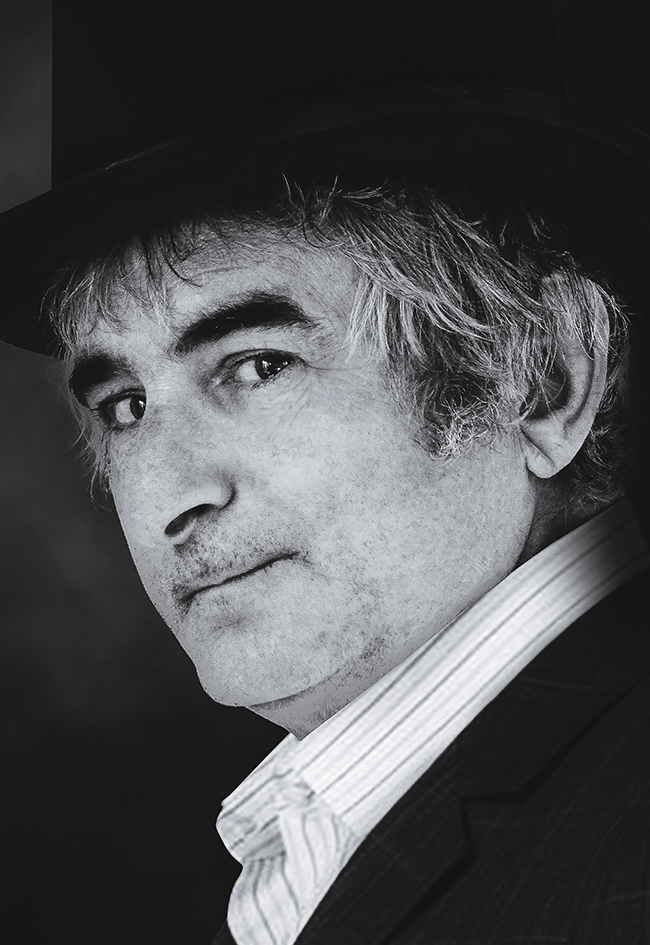

Malcolm Pryce was born in the UK and has spent much of his life working and travelling abroad. He has been, at various times, a BMW assembly-line worker, a hotel washer-up, a deck hand on a yacht sailing the South Seas, an advertising copywriter and the world's worst aluminium salesman. In 1998 he gave up his day job and booked a passage on a banana boat bound for South America in order to write Aberystwyth Mon Amour. He spent the next seven years living in Bangkok, where he wrote three more novels in the series, Last Tango in Aberystwyth, The Unbearable Lightness of Being in Aberystwyth and Don't Cry for Me Aberystwyth. In 2007 he moved back to the UK and now lives in Oxford, where he wrote From Aberystwyth with Love, The Day Aberystwyth Stood Still, and, most recently, The Case of the Hail Mary Celeste.

Visit Malcolm's website here or get to know him a bit more by following him on Twitter.

Find out more about titles and buy the latest releases from Malcolm Pryce at Bloomsbury.com

Comments