Debut author Annabel Abbs talks learning the writing craft via osmosis, with Joyce, Beckett and DH Lawrence as inspiration.

When I started writing my first novel, I knew only that I wanted to create a fictional biography of a 1920s dancer called Lucia Joyce. I had never been on a writing course or read a creative writing manual. Fortunately, Lucia was the only daughter of James Joyce and a large part of her story featured Samuel Beckett. My early research involved reading and re-reading their collected works and pouring over various biographies. As I did this I learned huge amounts, almost by osmosis. I learned how they worked. I saw how they responded to failure, to rejection, to criticism. These lessons stayed with me for the following three years as I wrestled with my half-formed novel – often at night and always on my own. I didn't have the luxury of a writing group or a mentor and my book was so research-intensive I had no time to attend a course of any sort. Instead I stuck photos of Joyce and Beckett (and later DH Lawrence) all over my study wall and they became my writing buddies.

So what exactly did I learn?

BORROW FROM OTHERS: Joyce and Beckett were shameless magpies, borrowing extensively from other writers. Beckett kept a notebook in which he wrote down every word or phrase he liked and then adapted it for his own work. I followed suit. Every time I came across a word I liked, a beautifully phrased sentence, an intriguing way of describing a person or place, I wrote it down. Then I played with it: I trying to improve it, reconfigure it, tighten it. This microscopic analysis enabled me to see how great writers work with language at the most basic level.

ECONOMISE: Beckett and Joyce (in his early work) were both masters of economy and brevity, able to convey complex ideas or emotions in a single, pithy sentence. This understanding of economy helped me cut out 2000 words of repetition from my first draft of The Joyce Girl. My second novel features DH Lawrence- who is not a master of economy. Reading his work reinforced the need to remove repetition and reminded me never to labour a point.

WORK, WORK, WORK: Joyce, Beckett and Lawrence worked compulsively. Joyce worked with hangovers, with appalling eye disease, and while in acute pain. Beckett took himself off to his small house in the French countryside and spent weeks at a time entirely on his own, just writing. Lawrence wrote prolifically – rarely planning, just diving straight in. None of them insisted on special desks or waited for the Muse. Lawrence often wrote sitting against a tree and Joyce frequently worked on his bed using his suitcase as a desk. I followed suit, writing on the edge of football pitches and in supermarket queues, for example.

EDIT, EDIT, EDIT: Beckett is, of course, the master of paring down. But all three wrote and rewrote. Lawrence wrote Lady Chatterley’s Lover three times from scratch – with an ink pen! Anecdotes like this gave me the courage to delete endless drafts and start again.

EVEN GREAT WRITERS WRITE RUBBISH: All three wrote and published some pretty awful stuff. When I had a bad writing day, I reminded myself that even so-called great writers produce rubbish sometimes. My advice? Put it away and go for a walk.

EXPERIMENT: All three wrote in a variety of forms: poems, plays, essays, novels. Often one technique seemed to inform another. And Ulysses is, of course, a hugely experimental novel. Eimear McBride famously said that reading Ulysses made her realise there was no set way to write a novel. My writing is neither experimental nor Joycean, but Joyce gave me the courage to ‘have a go’, to play around with interior monologue, dialogue, structure, tense. The range of their work is also a salutary reminder that one doesn't need to confine oneself to a single genre.

EXPAND YOUR VOCABULARY: Joyce has an enormous vocabulary and from him I learned not to shy away from unusual or made-up words. Often the sound or rhythm of a word give it implicit meaning. Anna Hope used a similar technique when she resurrected old Yorkshire words in The Ballroom. In an age of text-speak and tweet-code, I think there’s a growing enthusiasm for more interesting vocabulary.

COURAGE AND RESILIENCE: All three writers had enormous courage. They often refused to let editors tamper with their manuscripts. When editors were suggesting changes to The Joyce Girl that I didn’t agree with, although it was my first novel and I was wracked with doubt, I drew strength from these men – and refused (sometimes!). All three writers also included outrageous and shocking (for the time) content, refusing to meet the propriety standards of the day – even when this meant having their books banned. This takes guts. I wrote one chapter that makes me feel very uncomfortable (in a what-will-the-neighbours-think way) – but I tell myself if they could do it, almost a hundred years ago, I can do it now.

PROSE STYLE: Lawrence’s descriptive writing is superb. Some of Joyce’s prose is extraordinary. I turn to specific paragraphs again and again and I have a few of their paragraphs stuck to my wall – to inspire me on those brain-dead days when nothing flows.

Although it was the women in their lives who impelled me to write, it was the craft and practice of Joyce, Beckett and Lawrence that helped me shape my work. And for that I am grateful…

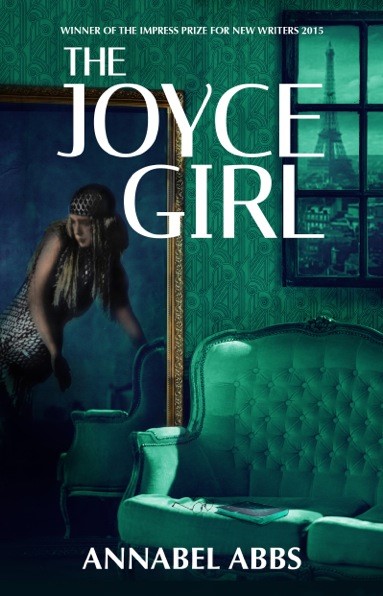

The Joyce Girl is published on 16 June by Impress. It won the Impress 2015 Prize for New Writers, was longlisted for the 2015 Bath Novel Award and the 2015 Caledonia Novel Award, and was shortlisted for the 2015 Spotlight First Novel Award. It’s since been sold to several countries including Australia and Germany. Annabel Abbs lives with her family in London and Sussex. The Joyce Girl is her first novel. Find out more on her website or follow Annabel on Twitter.

Comments