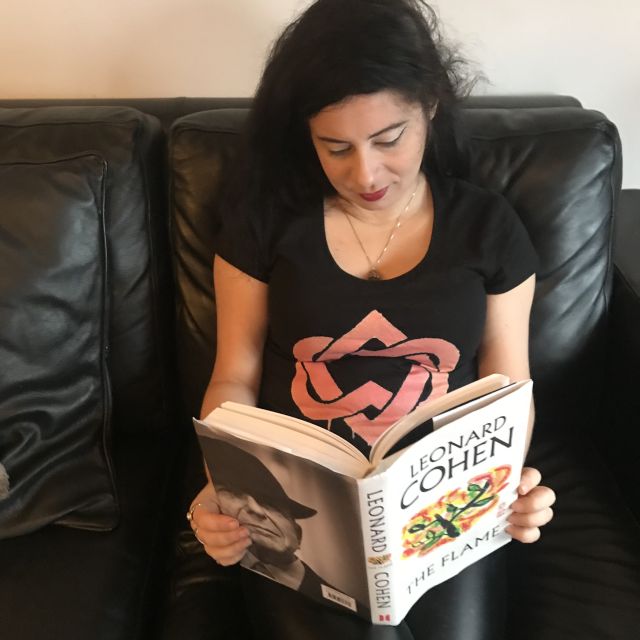

From The Flame by Leonard Cohen (Canongate)

Leonard Cohen’s poetry was sometimes set to music, sometimes sung, sometimes accompanied cartoons, sketches and symbols – the Order of the Unified Hearts intertwining two Stars of David with heart-shaped bends at their tops; the brimmed hat he would doff in concert to the music, to its source, to his audience, to life itself – but whether it appeared in books or in albums, it was always poetry first.

The Flame is edited posthumously, and published just under two years after Leonard Cohen’s death on 7 November 2016. There is a foreword by his son, Adam Cohen, and his editors by Robert Faggen and Alexandra Pleshoyano, in which each says of Leonard Cohen what Leonard Cohen so often and well said of life itself: how unworthy we feel our choices might have been, how unequal we feel to the task. Yet what his verses, his music and, yes, his singing, taught with heartbreaking clarity was that that very appreciation – that gratitude – was the task.

The layout of The Flame, though not the title, was chosen by Leonard Cohen. It comprises three sections, the first of which is sixty-three complete poems, the second those that became lyrics for his final four albums, the third a selection from the journals he had kept from his teenage years throughout his life (everywhere, Adam Cohen tells us, from his jacket pockets to the fridge). It also contains his acceptance speech for the Prince of Asturias Award and his final email exchange with Peter Scott, a friend and colleague, written 24 hours before his death. In terms of what writing voice is and where it originates, it would be hard to find better writing advice though none of it is phrased as such (except, perhaps, for “If I knew where the good songs came from, I’d go there more often”).

The title was Adam Cohen’s choice, one of Leonard Cohen’s recurring symbols of life, death (from Joan of Arc to You Want It Darker) and the words that go before and beyond. Like the symbol of the flame, he revisits what love is, what it demands, what memory clarifies and what it leaves out are found with dark humour and exquisite perception turning any apparent certainty, any definitive conclusion, upside down in the final line. As a teenager, I remember asking my mum what it was about this man. Roughly what she said was he spells out the utter truth, then in a final line turns it on his head. She didn’t say that’s what it’s like to try to understand anything in this world, from a person you love to the world you’re in to existence itself; she let me find that out for myself when I was ready to listen. And here it most definitely is. “Hineini”, a recurring phrase in the Jewish bible meaning “I am here/here I am”, chimes with Cohen’s consciousness of the need to be as fully present as we can, while we can (“we are so lightly here”). He turns even this on its head in You Want it Darker, yet never deletes the positive in favour of the negative or vise versa. He writes exquisitely clear perception about the limitations of perception, with the gratitude of one looking at life as one does in love: noticing, appreciating, awed but not afraid, a voice that is grateful and present to the end.

Rachel Knightley's short story, 'Before I Walked Away', appears in Uncertainties III (Swan River Press) and was recommended this month in the Washington Post for where best to find the best in modern Weird Fiction. Another short story, 'Duty of Care' was published on 1 November in the Woman's Weekly Fiction Special. Her stories have previously won the 'Promis' Prize for Children's Fiction and first place in Writers' Forum's fiction competition. She is completing her PhD novel in 2019. She runs Green Ink Writers’ Gym for writers of all genres and levels of experience. Say hello or find out more at www.rachelknightley.com and www.greeninkwritersgym.com

Comments