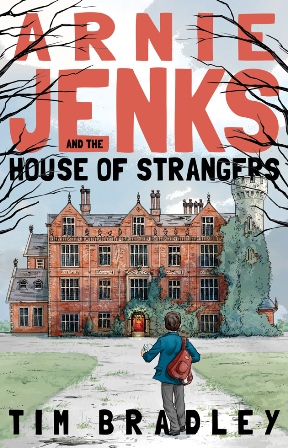

In a series of articles for W&A, self-published author Tim Bradley explains the process of writing his first children's novel, Arnie Jenks and the House of Strangers. In this second instalment, Tim discusses how it felt to have his work looked at by a professional editor, and what he learnt from the process.

Part Two

Is ‘Arnie Jenks and the House of Strangers’ fit for purpose?

I’d been introduced to Philippa Donovan who had established Smart Quill Editorial, which offers bespoke author services editing manuscripts to ensure they are ready for submission and publication. Vital support for people like me. Outlining my work-in-progress, as I was concluding my first draft, she thought my idea had potential.

Several slightly unsettling weeks passed. Then the notes arrived.

Her report was comprehensive, detailed and honest but very supportive of what I’d written. A considered, thorough going over of what needed re-balancing, re-working and re-evaluating to allow the material to shine. Fantastic! I opened my computer. Then I read on…

“Do nothing for a fortnight, put the manuscript in a drawer and leave it there while you let the notes sink in.”

Eh? But I want to get on with it!

I eyed the drawer daily but resisted the temptation to start the next draft as the notes and comments continued to jostle in my head.

Some of the humps in the road that needed levelling included:

- What does Arnie Jenks actually look like?

I’d assumed that the reader would imagine him as they’d want. But after canvassing further I accepted the argument that “we need something to build on, you’ve only told us his age!” So I applied my prescriptive pen and added explicitly height, weight and colour of hair and other physical attributes - how he held himself, ran and, rubbed his shoes together from time to time when in a tight spot. I was told my secondary characters such as Thomas, a First World War soldier fleeing from the Battle of the Somme were more vivid in comparison to Arnie. Perhaps because they appeared on fewer pages and had to make a strong impact. Arnie could grow more gradually - he had 23 chapters to play around in - but his character required defining.

- Don’t overburden the young reader with too much historical detail – they might get lost in the story.

I’d been keen to stress the historical flavour of each era so had written a page or two of description by way of introduction. However, slimming these opening passages down considerably, pegging additional nuggets of detail either side of new dialogue, from Arnie in particular, really helped drive the narrative more effectively.

- Make sure as much of the narrative is explored and channelled through your central character.

I’d written a number of passages where Arnie’s presence or contribution was marginal; for example, him watching events take place between others through a crack in the door or letting guest characters take over entire scenes. Once I’d flicked this switch in my head I found that channelling events through Arnie allowed him to take the lead more frequently.

- Don’t pose a question and leave it unanswered without reason. (The younger reader might wander)

I’d fallen into this trap headfirst. I’d thought it would add mystery rather than confusion, but seemingly not. Also, because Arnie is the conduit for the reader he might appear baffled too!

- Emily comes and goes without logic or reason.

Emily is a servant girl working at Shabbington Hall in 1900. When Arnie’s visit to Victorian times ends, she’s transported with him to the present day. In my early drafts I hadn’t fully explored her shock and feelings of this happening and how her insight, knowledge and background could contribute to Arnie’s understanding of his time travelling adventures. Also, does she have special time travel powers too? And why her? No one else Arnie meets travels with him, so I needed to define these rules to make her believable and relevant.

- Though Shabbington Hall can provide endless possible locations to write for – is what you’ve stated consistent?

So, I formalised a map based on several historic houses I’d surveyed, so exits and entrances and key vantage points would link up geographically. Shabbington Hall’s layout can always alter a little in future books as it was constructed over the centuries, but it’s good for me to know what I’ve nailed down.

- Your first scene needs to be exciting and grip the reader.

I’d originally opened with the arrival of the school bus delivering Arnie and his chums to the house. But this jolly set-up bit the dust and a skateboarding incident, which almost knocks over his teacher, was introduced as a replacement to drive the character into the heart of the story and keep the reader hooked.

- Show not tell.

I thought I had been doing that. But upon examination, I realised that I had been telling more than I knew. So I revised.

Tell: Arnie sensed the foul smell.

Show: “What a stink!’ he spluttered, screwing up his nose.

Tell: 'Arnie could see that the window was almost certainly stuck.'

Show: ‘It won’t budge,’ Arnie spat, rattling the window catch.

AND FINALLY…

- You need to have closure

Hadn’t I done enough? The reader would surely understand the need to wait until the next book in the series to learn how Arnie deals with the fallout from discovering the truth about the house and its secrets?

"NO!" came various replies. “Cliff-hangers might be fine for television series but not in this case. The reader will feel cheated or at the very least disappointed. You can’t leave your hero in emotional peril at the end of the book! Especially your first book - you may never be trusted again."

So taking that all on board, I introduced a final character that helps Arnie resolve his situation before he goes home. This breakthrough, several further weeks' work and a subsequent polish produced a manuscript ready for what I hoped would be the final stage.

Tim Bradley was born in Portsmouth in 1964. After obtaining his degree from Southampton University he joined the BBC where he became a producer in television drama. In 2000 he left to freelance. Works include Teachers (Channel 4), Primeval, Unforgotten (ITV), Silent Witness, D-Day and Death in Paradise (BBC). He lives in Buckinghamshire with his wife, son and dog. Arnie Jenks and the House of Strangers is Tim’s debut novel for children aged 9-13 years. Follow him on Twitter here.

Comments