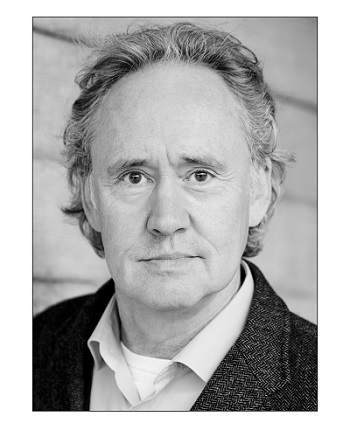

Comedian, actor and writer Nigel Planer shares his thoughts on writing comedy ahead of his summer teaching comedy course at Casa Ana, a writing retreat in Spain.

A few years ago, I was asked if I would conduct a workshop on the subject of “Writing Comedy”. Not an unreasonable idea, except that after a few days of thinking about it, I reached the conclusion that some people are just funnier than others, and apart from telling students to write some jokes, there wouldn't be a lot I would have to offer. There’s nothing worse than people trying to be funny, so by a logical extension there would be nothing worse than trying to make people funny.

But, in the same way that trying not to cry can often be the best way for an actor to bring out the tears, trying not to be funny can sometimes bring about the best results. A compere announcing you as the ‘funniest man in Camden’ is, I reckon, the kiss of death. I have toured both as a stand-up character comedian and as a performance poet and found that laughs were easier to come by when I went out with a serious expression on my face and told the audience I was going to read them some poetry about my divorce. So perhaps there would be a way to approach writing comedy through looking at tragedy.

Because the line between serious and funny is about as thin as a Rizla paper. And not even an orange Rizla paper. It’s one of those almost see-through blue ones which may get blown away by the slightest little breeze.

The ‘How-To’ plot structure manuals tend to get a bit lost when it comes to comedy. Comedy can disobey rules as long as it’s funny. But in theory at least, plot structure should be the same in comedy as in tragedy. It’s all story-telling, after all.

However, there is one tangible difference between comedy and ‘drama’ which tends to get overlooked; and that’s character type. Comedy tends to have two dimensional or ‘flat’ characters, as EM Forster called them, while drama is more likely to have ‘round’ or three dimensional ones. On TV, as we all know, ‘drama’ means anything with a detective in it. But in this instance I am talking about drama in the wider sense of that which is not comedy.

By two dimensional, I mean characters who have a single attribute which defines them, who are not changed by the events of the plot. Preferably this attribute will not fit the circumstances in which they find themselves; think Captain Mainwaring, incompetent and in charge, or Roy from the IT Crowd, needy but completely lacking in social skills. These are character archetypes that go back hundreds of years, that we see repeated again and again; the show-off soldier who’s a coward, the cheeky servant, the stupid boss, the bossy wife, the man with an uncontrollable temper. They can be traced from Punch to Basil Fawlty. A comedy character is instantly recognizable and is the same every time they come in. The moment they are changed by the plot, rather than having their flaws dictate the plot, they have become three dimensional, and we have lost them. We don’t want to see Captain Mainwaring, for instance, realizing that he has ignored his wife and “going on a journey”. Leave journeys to heroes and knighted playwrights.

An interesting side note to this, is that almost all of Dickens’ characters are two dimensional. Dickens “ought to be bad” – E.M. Forster again – “yet he’s one of our big writers”. Forster concludes, in ‘Aspects of the Novel’, that there may be more to flatness than comedy-bashers would care to admit.

So, while the How-to-Write shelves are filled with books that insist on the importance of plotting and structure, it’s character that we return to, characters we remember, and characters that keep us reading, watching, listening. However many dimensions you give them.

It was with all this in mind, that I developed ‘Creating Funny Characters’ writers’ weeks for the Arvon Foundation, which later developed into a ‘Character versus Plot’ week. I've conducted several of them now, with guests as varied as Sally Phillips, Rani Moorthy and Vayu Naidu. This year I'm taking all these ideas and experiences, and conducting a week, with Sally Phillips, at the Casa Ana writers’ retreat in the beautiful Alpujarras in Spain.

For most people, a retreat is somewhere they would go for a break from the everyday stresses of their work. A writer’s retreat, on the other hand, is where those stresses take place. When all of the seminars, writing groups and workshops come to an end, the writer is still confronted with a blank page and the workings of his or her own mind.

Which is why I think it’s good to have other people around and to be in idyllic surroundings. Days are spent working, but at meal times there are others to have a laugh with, and evenings looking at the sun going down on the other side of the mountain. It’s just about the perfect environment to unleash whatever it is that needed unleashing.

Places are still available at the 'Making It Funny' comedy writing workshop, which will take place from 30 July - 6 August at Casa Ana, Las Alpujarras, Spain. For further details, visit their website here and contact Anne at Casa Ana for bookings:

E: [email protected]

Tel: 0034 958 766 270

Nigel Planer was a founding member of the Comedy Store and the Comic Strip group, and went on to star in the seminal TV series 'The Young Ones' and 'The Comic Strip Presents'. Nigel regularly teaches and runs workshops for actors and for writers at the Arvon Foundation, the Actor's centre and the National Opera Studio. This will be his first course at Casa Ana. Nigel has published novels, short stories, poetry and articles and was nominated for an Olivier award for his performance in Sam Mendes' "Charlie and the Chocolate Factory" at the theatre Royal, Drury Lane.

Sally Philips is a comedy actress and writer, who has starred in the likes of Miranda and Bridget Jones. Sally co-created and wrote Smack the Pony, an all-female, double Emmy Award- winning comedy show.

Comments