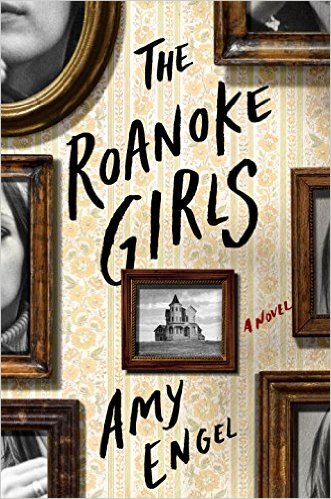

Debut novelist Amy Engel discusses the crucial decision of choosing the best way to tell a story.

My debut adult novel, The Roanoke Girls, tells the story of fifteen-year-old Lane Roanoke who goes to live with her maternal grandparents and cousin, Allegra, after her mother’s suicide. Lane knows little about her mother’s family other than they are wealthy and live on an estate called Roanoke in rural Osage Flats, Kansas. At first, Lane welcomes life as one of the rich and beautiful Roanoke girls. But over the course of a single summer, she realizes all her family legacy entails and she runs, fast and far away. Eleven years later, Lane is scraping by in Los Angeles when she receives a phone call from her grandfather telling her that Allegra has gone missing. Lane reluctantly returns to Roanoke to help search for Allegra and to assuage her own guilt at having left Allegra behind all those years ago. The novel shifts in time between Lane’s first summer at Roanoke and the summer of her return, exploring the secrets families keep and the fierce and terrible love that both binds them together and rips them apart.

One of the first things an author has to decide when he or she sits down to write a novel is how best to tell the story. It sounds like a simple task, but there are multiple variables to consider. One point of view or multiple voices? Present or past tense? First or third person? Or even second? I knew early on that The Roanoke Girls would be filtered mainly through the point of view of a single narrator, Lane Roanoke. But Lane’s story isn’t one that can be told only in present time. Lane’s past constantly reaches out and shapes her present. That’s true of all of us, of course, but that sense of being unable to escape the past is especially fraught for Lane. I didn’t think simply having her reflect on or remember her past would be enough to give the reader a real sense of Lane or the pain and obstacles she’d dealt with in her life. A dual narrative, past and present, seemed like the best and most effective approach to take with The Roanoke Girls.

As I began writing, I was well aware that often readers have an issue with dual timeline narration. There is always the risk that one of the timelines will be more interesting than the other or that the timelines will feel disjointed and leave the reader confused. For me, the best way to attempt to avoid those traps was to write the book as it was meant to be read. Meaning, I didn’t write all the present day sections and then go back and write all the past sections and, at that point, meld them together. Instead, I wrote the novel section by section as they appear in the book: past, present, past, present, etc. I know this method might not work for every writer, but for me, it allowed me to always be aware of just where I’d left off in a particular timeline and gave me the ability to craft each section in a way that the past and present flowed together in a coherent narrative even when the events described were separated by over a decade in time.

The two summers explored in the book are the most crucial of Lane’s life. There would be no way to tell her story without giving both time periods equal attention. It was also important to the story to have Lane’s first summer at Roanoke as a fully developed narrative thread because it gave the reader a real sense of Allegra and the bond she and Lane shared. Because Allegra is missing in the present day narrative, not having that past narrative would have left a big hole where the reader’s concern for Allegra should have been. I didn’t want Allegra relegated to the role of generic missing girl. I wanted the reader to care about her and be viscerally concerned about her fate. Likewise, giving the reader a full picture of Lane’s first summer at Roanoke makes clear the joys that Roanoke offered, as well as its dark heart. Because of this, the reader is well aware of not only what Lane is risking by returning but also why she might be helpless to resist the call of home. Now that it’s a finished novel, I honestly can’t imagine The Roanoke Girls working with any other type of narration.

The two summers explored in the book are the most crucial of Lane’s life. There would be no way to tell her story without giving both time periods equal attention. It was also important to the story to have Lane’s first summer at Roanoke as a fully developed narrative thread because it gave the reader a real sense of Allegra and the bond she and Lane shared. Because Allegra is missing in the present day narrative, not having that past narrative would have left a big hole where the reader’s concern for Allegra should have been. I didn’t want Allegra relegated to the role of generic missing girl. I wanted the reader to care about her and be viscerally concerned about her fate. Likewise, giving the reader a full picture of Lane’s first summer at Roanoke makes clear the joys that Roanoke offered, as well as its dark heart. Because of this, the reader is well aware of not only what Lane is risking by returning but also why she might be helpless to resist the call of home. Now that it’s a finished novel, I honestly can’t imagine The Roanoke Girls working with any other type of narration.

Amy Engel is the author of The Book Of Ivy young adult series. A former criminal defense attorney, she lives in Missouri with her family. The Roanaoke Girls is her first novel for adults. Follow Amy on Twitter here.

Comments