Some time ago I was asked by a novelist of world renown why I - a woman – had written a novel featuring a male protagonist. Did I not think (as a woman) that it might be more appropriate to have a female protagonist? Was I not (as a woman) interested in the female experience?

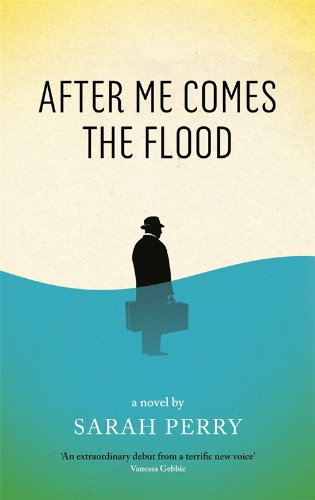

I was a little taken aback, and aside from looking down to establish that yes, on all visual evidence I was quite inescapably female, I didn’t really have a satisfactory answer. After Me Comes the Flood deals with the confusion of a lonely man who deceives his way into an eerie and isolated house. I had never questioned his gender: he was simply my John, and I lived in him and with him, and it never occurred to me that I’d somehow transgressed. The truth was – and I couldn’t possibly have said it at the time, and I’m not sure I ought to be saying it now – that not only do I not think of myself as a woman writer, I’m not entirely sure I think of myself as a woman.

Before I try and unravel what I mean by this (and almost certainly get tangled up in the process) it’s helpful to ask what prompted this question. At least in part it came, I suspect, from that wretched truism that writers ought to write what they know. If ever an aphorism hobbled the imagination more than this, I’d be very surprised. It has been wheeled out in Creative Writing tutor groups and hand-outs across the globe for decades, convincing post-grads they must write fevered student intrigue and men just turned 60 that they must write with wry melancholy about the prospect of ageing.

The truth is that you can only write what you know: there isn’t anything else. But what you know is not where you grew up, or who broke your heart, or what your mother said – it is in your perception of all these things, and the consciousness that formed your perception, and the unreliability of your memory, and the imagination that plugs the gaps, or takes fragments of recollection and runs with it until you can no longer see the starting point and don’t want to, either.

It has also, I suspect, contributed to the notion that writing is gendered: that women will necessarily evoke the ‘female experience’ and men the male; that there are essential differences in perception and understanding that cannot be bridged; even that there is such a thing as a ‘female experience’. Rather, the consciousness, perception, memory and imagination that form what you know stand above and apart from experiences lazily allocated male or female (Babies! Road trips! Boyfriends! Work!).

The literary rock-stardom of Karl Ove Knausgaard serves to demonstrate how absurd it is to expect a certain kind of writing from an author dependent largely on their gender. His painstaking unpicking of domestic life is praised to the skies partly on its own extraordinary merits, but partly because of a collective in-drawn breath at the almost miraculous achievement of a man – a man, mark you! – writing not only about children and parenthood but also (brace yourself) about his feelings. When Rachel Cusk did similar in her laceratingly honest memoir of motherhood A Life’s Work, she was simultaneously looked on askance for being a woman writing about domestic life, and condemned in certain quarters for having unapologetically challenged conventional motherhood tropes.

This is the pernicious effect of expecting writers to be led by their biology: not only are women writers in particular expected to evoke and examine a fairly narrow slice of human experience, but in doing so their writing is side-lined. Worse, if they fail to acquiesce to social expectation they risk the media equivalent of the stocks, or being designated ‘bad girls’ as if they’re children stepping charmingly out of line.

I said that I hardly think of myself as a woman, and this is true – at any rate, in respect of social constructions of womanhood. I am not a mother, and so I cannot define myself in those uniquely female terms; I married young, and so my womanhood and sexuality have never led my social interactions. Sheer good fortune has spared me the misogynistic and violent behaviour so appallingly the lot of the female majority. I have never felt professionally disadvantaged because of my gender, and if I have experienced more than a handful of sexist slights I’ve been largely oblivious. Perhaps because of all these things (and more) my being a woman only rarely occurs to me, in quite a detached and disinterested way - in the same way I notice now and then that I have small feet.

Has my gender shaped my perception and my imagination? It has – it must have done. But my being a woman is the beginning of my understanding, and not its end. This being the case, it never once occurred to me that I ought not to have a male protagonist. Why shouldn’t I? John Cole is lonely, he is confused, he desires and despises. He tries to understand, he fails to; he tries to help, he can’t. These are neither male nor female traits, they are only human. Would he have been a different character - would I have written a different novel - if he had been female, if I had been male? I’m unconvinced. Besides, I can’t ever recall having decided that he would be a man: there he simply was.

So then: write what you know – write everything you know: you can’t help it, and it will be more than enough. But though your sex and sexuality will form and shape what you know, don’t be tricked into thinking it sets a boundary you must not cross.

Sarah Perry was born in Essex in 1979, and grew up in a deeply religious home. Kept apart from contemporary culture, she spent her childhood immersed in classic literature, Victorian hymns and the King James Bible. She has a PhD in creative writing at Royal Holloway which she completed under the supervision of Andrew Motion. She has been writer in residence at the Gladstone Library and is the winner of a Shiva Naipaul award for travel writing. She lives in Norwich.

To visit Sarah's website click here, or you can find her on Twitter (@sarahgperry) and Facebook.

Comments