One upon a time, a group of editors sat around a table, brainstorming ideas for a new children’s series for girls aged 6-9.

It needed to be collectable with a strong series identity. One editor put up her hand. ‘I had an idea for a series when I was seven years old,’ she said. ‘It was about seven fairies. One for each colour of the rainbow.’

The series Rainbow Magic by Daisy Meadows has since spawned over 200 titles. Sales of the series currently stand over ten million copies worldwide.

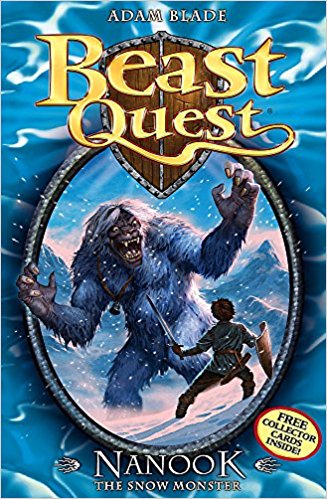

You might assume on those statistics that Rainbow Magic has made its author rich. It has, but not in the way you might imagine. If you remember, it was an editor’s idea. Daisy Meadows herself doesn’t exist. She is an amalgam of dozens of different writers and editors, all of whom have taken a share of her profits. The same is true of Lucy Daniels – whose Animal Ark series could be said to have started the whole series fiction phenomenon in the 1990s – and Adam Blade, more recently of the Beast Quest series. Why do publishers produce books in this way?

A fictional author has no rights over a series, which makes that series more flexible and profitable for a publisher or a packager. A fictional author can also write six or more books at the same time, which does wonders for a publisher’s production line and (you’ve guessed it) profits. A fictional author can be designed to fit a niche in the market. They can be given an alphabetically appropriate name to meet a browser’s eye level or queue-barge onto the shelf ahead of the direct competition. They can be designed to fit as many commercial platforms as possible, should opportunity present: clothing, online games, stationery. They can also enjoy lives far more exotic than those of real authors. Adam Blade’s biography charmingly gives him a pet capuchin monkey called Omar, while Lucy Daniels apparently lives in Yorkshire with Russian Blue cats.

There are dozens of well-known authors now established in their own right who have written packaged series fiction at some point in their careers. Advances aren’t high, but the steady stream of royalties and the great and glorious mysteries of PLR income often mean that the projects are worthwhile.

And here’s the good news. Commercial fiction packagers don’t need established names to write for them. They simply need writers who can write and who are able and happy to follow a detailed brief.

If your ego can take it, writing series fiction is an incomparable crash course in how to write. I learned a vast amount at the coalface as Lucy Daniels/Adam Blade (yes, I’m both) about pacing, plotting, cliff-hangers, world-building, character development, and all those other building blocks of successful storytelling. You work closely – often line by line – with expert industry editors, whose practical advice and guidance can feel like a creative writing course without the fee. Instead, miraculously you are the one who gets paid. There’s even a published book to show for your efforts at the end of it all.

Lucy Courtenay began her writing career in 1999, starting work on The Sleepover Club, before joining Working Partners to work on Animal Ark, Dolphin Diaries and The Pet Finders Club. She wrote Naughty Fairies for Hodder Children's Books as an antidote to all things pink and glittery. The series of six books was launched in 2006, with a further six published in 2007. Her next series, Scarlet Silver, was published by Hodder Children’s Books in 2009, with Animal Antics for Stripes following in 2010. In 2011 her children's fiction series Wild was published by Hodder Children's Books, followed by the romantic comedy The Kiss in 2015. Her non-fiction writing guide Teach Yourself: Get Started in Writing an Illustrated Children's Book, was also published in 2016 by John Murray. Her latest book Movie Night, a young adult romantic comedy, was published in January 2018 by Hodder Children's Books.

Comments