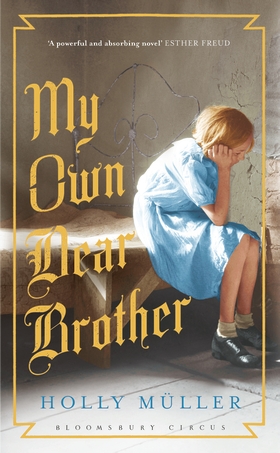

Debut author Holly Müller discusses her immersive research methods for her novel 'My Own Dear Brother.'

In the summer of 2009, I put my possessions in storage, terminated my UK rental agreement, and moved to my cousin’s empty apartment in Vienna. From this romantic and crumbling base, I researched my debut novel My Own Dear Brother.

Set in Austria during the latter stages of World War Two and the turbulent post war era when brutal Russian troops flooded the country, I’d given myself a tough task: to portray a foreign place, a distressing and complex period of history, and lesser-known aspects of the war.

Interviewing elderly Austrians to gain insight into these hidden stories was one of the most intense experiences of my life. Outpourings of memory that would soon be lost, accounts of trauma, resistance and defeat, of complicity in Nazi cruelty, and terror about the approaching Red Army. Via my Austrian family (I'm half-Austrian on my dad’s side) I contacted people as old as ninety, surprised how many were willing to meet, despite the gruelling questions I’d pose. Too raw, too close for comfort to ask my own Austrian grandfather, who’d been pro-Nazi, an eager Hitler Youth member, a German soldier, I was desperate to understand the uncomfortable realities.

Together with an interpreter, I traveled to mountain villages, to manicured wooden homes in Lower Austria, and tidy flats in the Viennese suburbs. I was welcomed with coffee, cake and whipped cream into gemütlich living rooms.

One eighty-seven year old talked for hours in incredible detail. She told of thirty Russians invading her childhood home, one soldier climbing to the attic room to peer in at her, a silhouette in the doorway. She showed me the former site of a small concentration camp, directly opposite her house. A memorial now marks the spot, listing an approximate number killed. During the war, she saw prisoners herded by guards along the street, forced to build walls or dig graves. ‘Pitiful,’ she said of their bare feet in winter, their emaciated bodies. ‘They looked so cold. But what could I do?’ Later she said ‘I was a Nazi back then.’ Anxiously she asked me not to disclose her name.

As I left, she gripped my hand, wished me luck with the book; she hoped we’d meet again. I felt a little shocked, a little choked. It struck me she’d needed this. Perhaps her last chance to speak without reserve, perhaps only possible because she knew she’d never see me again.

Another interviewee was quite the opposite. Eighty-nine and very sharp – a city-dweller – she’d resisted the regime. ‘I took one look at Hitler and knew he meant war. Why didn't everyone see that?’ Horrified, she’d taken action wherever possible. Drafted at a munitions factory, she’d ensured the bombs she constructed would never detonate, hoping to save lives and sabotage the war effort. Her speckled hands shifted in her lap as she described the final siege of Vienna, how desperate conscripts fought the tide of Soviets and how she’d stood in the street and persuaded men to lay down their arms. ‘It’s hopeless,’ she’d told them. Beside her, a pile of weaponry grew. If patrolling SS had caught her, she’d have been executed on the spot – no doubt. All this she’d done whilst raising a son by herself.

The interpreter and I shared a look of admiring disbelief.

If I’d known then just how sensitive and highly charged is the subject of Austria’s Nazism, I don’t know if I’d have dared begin. I was, as someone put it, ‘pressing on bruises’. But I met with almost no hostility. A retired judge in his sixties said it was wonderful to meet someone so curious, that not many people knew, or asked about Austria.

He told of Austria’s culpability, but also its suffering. He’d a keen interest in history, and showed me replicas of Nazi propaganda, an old copy of Mein Kampf, photos of the Eastern front, a dead horse spread-eagled in a deserted Russian town; a decapitated body in an army truck. In his cluttered apartment, the tall clock chimed many times before I was too tired to continue, my cheeks burning with the effort of communicating, with the intensity of what I was learning. ‘This very flat was commandeered by Russian officers during the occupation,’ he said. ‘My family had to squeeze into one room.’ Then, while showing me out, ‘My aunt was raped. A rejected suitor led the Russians to where she hid in the cellar. She finally told about it on her death bed.’ I tried to absorb this; tried to imagine.

Looking up at the Hofburg balcony where Hitler had addressed rapturous Viennese crowds in 1938, or dawdling amongst identical crosses marked Unbekannt Soldat (Unknown Soldier) in Zentralfriedhof graveyard, I wondered if I could do it all justice. The imperative to ‘get it right’ paralysed me at times. In the shaded apartment I tried to write, knowing this book was too important to abandon. I’d learned things few people knew, uncovered compelling stories, explored the moral ambiguity of my own background and another time. The process had been transformative and fascinating and the world of My Own Dear Brother had become deeper and more intricate. Histories now passing out of living memory were caught in a flickering light; I could see their shadows on the wall and was sure I could capture them.

A piece of fiction could never be real, but I’d persevere until I’d written something true.

Holly Müller is a novelist, short story writer, and musician. She is half Austrian and half Welsh and lives in Cardiff. Her debut novel, My Own Dear Brother, a historical fiction set in post war Austria, is published worldwide with Bloomsbury. She is currently working towards a PhD in Creative Writing and is the singer, lyricist and violinist in the band Hail! The Planes. You can follow her on Twitter.

Comments