The big problem with writing is its primary blessing: the lack of structure. We stare at a blank screen and go where we like. This is fine in principle. But the older I get the more I crave some kind of framework. Boundaries, perimeters within which I can stay happily confined and focus on what I have and making it better.

Nowhere is this more vital than in the revision phase of a book. The last few passes of a raw manuscript are, to me, as important as the writing phase. That final five per cent of effort can turn an average work into an excellent one. I know some people regard revision as dreary drudgery but not me. I love it. I’m also keenly aware that it’s my last chance to make a book better before it’s submitted to an agent or editor. Literally the last chance because here’s a savage truth: you can only read your own work so many times before you become blind to it.

When you finish a raw MS you will be able to improve it a finite number of times before your imagination gags at the thought of taking another turn at the windmill. Read the piece three times and you should be able to make it better. Extend that to, say, five and the law of diminishing returns will kick in; you’ll find nothing to change. Be foolish enough to read the thing eight times or so and you will become convinced you’ve turned out the biggest piece of crap since the invention of the alphabet. Which may be true. You just won’t be able to make a considered judgement about that.

For me three is the magic number. Once I’ve finished the last page, got the story into a sequence of parts and scenes I’m happy with, I know that’s how many times I will be able to look at it again, before an editor does, and make some kind of positive contribution. So I use an approach based on my own limitations to make the most of what remaining willpower and intelligence I have to make the book better.

Follow an established routine

There’s a template you can follow for this already. It’s the way books are managed in the real world. There the sequence is this…

First read. Editor. By which I mean your main editor who will look for big issues: does a character work, does the story fall flat at some stage, are there structural issues that need fixing?

Second read. Line editor. Someone who will look for small issues: spelling, punctuation, style, continuity.

Third read. The reader. Someone who picks up the book in a shop or a library. And all they will ask themselves is: is it any good? Does it keep me entertained? Do I empathise with the characters?

The logical way to deal with manuscript revision is to use these three views, in a different order. What I’m looking for here is that magical thing perspective. The ability to see my work the way other people will one day. If you try, that’s not so hard. Let’s shuffle those steps…

The three steps of revision

First read: The line editor view.

I want to get the little things out of the way first. I also like to signal the fact that the book has entered a new stage in its life. So the first thing I will do once every part of the story structure feels in place is get it out of Scrivener and into Word then back up the original version and turn on track changes. I work for publishers, remember, so I will be delivering in Word in any case. That has to happen somewhere along the way. Just as importantly moving a book from one platform to another makes it look different somehow.

It’s that perspective thing again. I don’t know why but things that are invisible to me in Scrivener, even though I’ve looked at a scene a million times there, will sometimes leap off the page once the same words are transferred to Word. That’s good. For the record I currently work in Scrivener on the Mac and export a Word document that I edit in Word for Windows 2010 under Parallels on the same Mac. This is because Word on the Mac is, in my view, a heap of dung. It takes almost a minute to load up the 195K manuscript of Killing II for example, while Word on Windows, even under Parallels, does it in a flash. Windows Word is faster, nicer to use, and in many ways more Mac-like. I like it a lot.

Right. So I now have my book in Word and I’m revising it on screen. Note: this is the only part of this three-stage process that happens at the computer. It’s donkey work really and I’m happy to do that as I work my way through the MS. What am I looking for? Spelling, punctuation, ugly sentence structure, sentences that can be shortened or broken up. This is a cleaning exercise. I want to get rid of all the cruft, anything that can be taken out without causing any problems.

Oh, and repetition. Yes, repetition. Like that. We all repeat ourselves. It’s the most natural thing in the world. Sometimes repetition can be deliberate; it is with a few key sentences in The Killing where I’m trying to make a deliberate point. But mostly repetition in a book is a stylistic tic that needs to be excised. If you follow the advice in Writing: A User Manual you will be noting down your habitual repetitions as you write in your book diary. This should help you cut out the offending words as you write. But you won’t get them all. We never do. So check for repetitions in this first read and make sure you write down what they are. If you don’t you’ll miss them.

Second read: the editor view

I’ve reversed the traditional workflow here, putting line edit before general edit, because that works for me. You may feel differently. That’s your choice. Writing’s about finding what works for you, not aping the habits of others. Juggle things to your own taste and ignore or follow as required. One reason I like this sequence is that it gets me away from the computer for the creative work. That first read happens at the desk. The next two occur away from it. I will read the book and then edit it later, not try to do the two simultaneously. That, I think, is a mistake. You may save days — and you may be sick of the damned thing by now. But you owe it, and yourself, a better chance, and for that you need to take your time and sit back to read the MS properly.

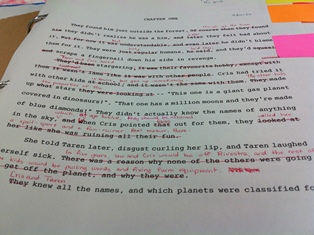

The simplest way to do this is the old-fashioned way. Print it out on A4, one and a half line spacing, or double if you like. Take those pages away somewhere (preferably a room without a computer). Lie in bed if you want. Get a red pen. Read and mark as you go. Can you do this on a tablet such as an iPad? Maybe. You’d have to decide. If you’re an iPad user you may want to look at two apps, Remarks and Notability, that mimic a pen very well, provided you have a decent stylus. I don’t think they’d be good enough for dealing with editing marks between you and a publisher, but they may well work at a personal level.

In the last revise we looked for little things. In this one I’m chasing big game. Do the characters feel right? Are physical descriptions consistent? Do they say too much or too little? Can I see, hear and smell the locations? Are there events in the narrative that feel a bit clunky?

Note: at the start of each writing day I read through the previous day’s work. So I edit throughout the writing process. This means that by this stage of the game I shouldn’t have any major structural issues that I can see (though the real editor may feel differently when the book reaches him or her). What I’m dealing with is excision and insertion. Preferably the former. Beginning writers often agonise over rewrites, wondering what they can do to make things better. Here’s a tip from experience: try cutting stuff out first and see if that works instead. Deletion is a positive act, good for the soul. Try it before inventing some new stuff that may only complicate matters further.

If I don’t end up with a shorter MS at the end of this process I’ll be very disappointed. The finished version of The Killing is 215K words long. The first version was almost 260K. Cut, cut, cut whenever you can, and then see what problems remain. You’ll be getting a lot more out of your editor if he/she is asking for inserts into the text rather than laboriously pointing out the flab.

After a week or two of slowly working through the pages I return to the computer, power up, and go through the corrections one by one, transferring the notes I’ve made with a pen onto the working version on screen (and occasionally disagreeing with them too — this is an active process so feel free to argue with yourself along the way).

Third read: the reader view

If the first two processes have gone well your book should be pretty much there. This is just as well since, the law of diminishing returns being what it is, you probably have only one more worthwhile pass of the MS left in you. Make the most of it. Forget you’re the author. Become the reader instead, or at least as close as you can get.

Here’s the simply way to do it. Print out your book using the two pages per printed page option in your printer. Fiddle around with the settings first. What you’re looking for is output that looks like a book galley — two pages of a paperback book. You may be thinking: why? They’re just the same words. And yes, they are. But you will see the thing differently, I guarantee, when the lines per page are transformed into the same format as a printed book.

Can you do this on a tablet? Up to a point. You can try to output a pdf in that format I suppose. Or turn out an epub or mobi file that you can read in Kindle or some other ereader. Give it a try and see what works for you. The key is getting that book page look. One drawback of ereaders is they won’t let you make annotations easily. You usually have to call up a virtual keyboard or something which I find a real pain. I just want to scribble with a red pen. The one device that will let you do this is the HTC Flyer, my favourite gadget of last year. With that you churn out an epub for the built-in ereader and mark up the results. It also does a good job with pdfs in the same way. Highly recommended still, even though it’s now a little clunky (and often discounted as a result).

What am I looking for in this revise? In short: to be entertained. I want to know if the book reads the way I want it to. Whether there are still passages that can be cut. If it feels right. Yes, I’ll spot a few typos and clunky sentences still, and they will be marked. But it’s the feel of the thing I’m looking for. Does it work?

I hope so. Because by the time I’m at the end of that third read I’m out of options. If everything has gone to plan I will return to the Mac and make one last set of changes. Then I’m through with the book as a personal project. It’s time to send it to the editor. Do I do this by saying, ‘I’ve finished the new book’? No. I say, as I always do, it’s now at a stage where I can add nothing more to it without outside intervention. Which, if I’ve done my job, will be minimal.

I take professional pride in delivering books that are as clean and as close to finished as possible. It’s not an editor’s job to fix a book. It’s the writer’s. Even for a massive project like The Killing books revision like this rarely takes much more than a month working five days a week. It’s time well spent in my view.

Revision matters. For a writer starting out in this game it could mean the difference between being published or not.

On Tuesday 24th July, 11am, David Hewson will be live on Twitter for a Q&A chat on the topic of writing and editing. Submit your questions to #DavidHewsonchat and follow @Writers_Artists and @david_hewson for his responses.

For seasoned writers the advice about editing and not going blind is probably right, but for first time writers there will still be lots of mistakes after only three edits. I think new writers have to go blind, put it aside, work on a new project for a while, go back to it and go blind again. Then you have to rinse and repeat until you think your work is the best you can ever make it because, given the competition new novelists face, mistakes are unacceptable.

I don't think it's David's fault he doesn't know this. As an ex-journalist he probably didn't spend long, if any time at all, in the slush piles. Those without professional writing background need a MS so polished it's positively shiny and a personality to match.

Thank you for this post David, I found it really interesting. I wrote my first novel and edited I don't know how many times with no real structure and at the end of it I was sick of reading it (alhough I still like the book). I'm now nearing the end of writing my second novel and think I will try using the technique you mentioned above as it seems to make good sense to me. Thank you

I'm on my fourth revision. I want it to entertain. The novel's been six years in progress with a couple of very long pauses, I've torn down more words than the final length will be. It does feel insane, Adrian :) All the time now I'm thinking, how and where could I simplify without disrupting the logic, which would mean tearing big plot walls down... again.

Last night, I was wrestling with a particular chapter as I went off to sleep, thinking, it's a big hub chapter, OK. Chapter 8 out of 50. A hub, but I'm not easy with it. I don't want more than three incoming spokes converging. Overload the chapter, and it risks becoming farcical. It's doing my head in today...and yet, I remind myself, if you make changes, no-one will know what isn't there now, that used to be there. Simplicity is not easy to achieve, first the swan's feet must paddle.

I have always revised as I've gone along, The danger with it is, you feel like you're weaving Penelope's loom, two steps forward and a step and a half back. David, you're right. You can become 'blind.' I discovered this having set the thing aside a few times, for months on end. Looking at it again, I had forgotten things, and I had moments where my eye went straight to something, and I thought, 'that's good, better than I remembered', and I also thought..'that's crap! What was I thinking of?'

This is a timely, companionable thread for me, thanks.