Robert Nurden's love letter to writing non-fiction, the essential elements that go into writing it well, and why its place in the market feels more vital than ever.

The less elevated role that non-fiction plays compared to the glitzy world of fiction can be detected straightaway in its lumbering prefix ‘non’. The type of writing in which facts are paramount is described in terms of what it is not. Hardly a good start!

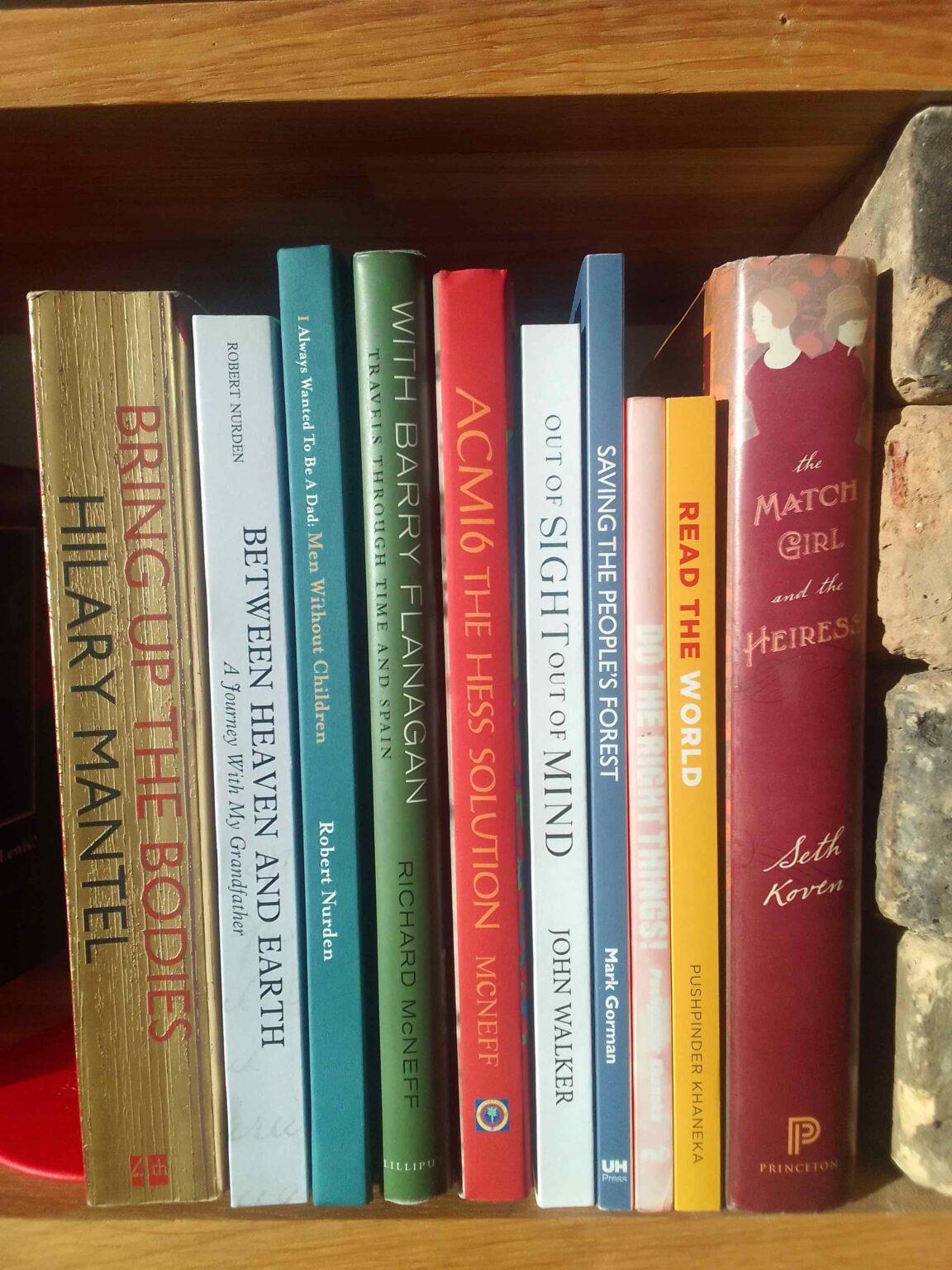

Biographers and historians like Hilary Mantel occasionally – and quite rightly – stand waving their blockbusters beneath the bright lights but, on the whole, it’s the creative writers of the imagination who steal the limelight.

But the mansion of literature has many rooms. And it’s in the sturdy basement that histories, journalism, biographies, autobiographies, memoirs, textbooks, instruction manuals and self-help books take up residence. Not forgetting reference works, criticism, opinion pieces, essays, blogs, promotional writing, science books and documentaries and countless other spin-offs.

It’s these genres, with their (hopefully) unstinting dedication to unearthing reality’s truths, that are the foundation for the more creative endeavours going on in the rest of the house. It’s here that objectivity, based on historical, scientific and empirical evidence, is supposed to reign supreme.

A good non-fiction writer will write into these existing genres so that the work is placed within its category. Readers can then easily locate it and it makes sales and marketing a whole lot easier. This, I would argue, takes quite a bit of humility; one is just a cog in an information machine.

However, in recent years, non-fiction has unwittingly assumed a new, vital role. It’s become an essential guardian of the truth. With fake news, AI and social media conspiracy theories staring us in the face, careful, honest telling of how it really is has never been so important. We need good non-fiction writers of prose like never before. Donald Trump won’t agree with me, of course, which only serves to strengthen my argument.

So, what’s required to produce good non-fiction? I’m going to divide the answer into three broad sections: research, writing and editing.

Research

Watertight research is all-important, as I quickly learnt when writing Between Heaven And Earth, the biography of my grandfather. I was alerted to hitherto unknown aspects of his life in a book of early twentieth century social history by an American historian. In just one and a half pages the writer managed to make ten errors of fact. On meeting him later, he admitted he’d invented things in order to spice up the narrative. “I never thought I’d meet his grandson,” he confessed. Moral of the tale? Just because something is written by an academic doesn’t mean it’s correct. This is echoed by Peter Williams, co-author of Forest Gate: A Short, Illustrated History: “Don’t publish things unless you are sure they are right. And always state your sources, as it is so annoying for readers years later if you don’t say where you sourced things.” And primary sources are gold dust to the researcher.

But, it’s also important to know when to stop. You shouldn’t include everything you find out. Every snippet of the subject you are passionate about may engage you, but your readers won’t necessarily agree.

Writing

It may seem an obvious thing to say, but you should be clear about why you’re writing your book. It may be you’re sharing a passion, imparting knowledge, instructing, telling a story or even fulfilling a commission you’re lukewarm about! Each of these aims will fit an established genre and a style that suits the material.

Writing quality non-fiction requires planning and attention to structure: whether that be chronological in the case of history and biography, step-by-step progression in books of instruction or logical, narrative flow in memoir.

Everyone has their own way of writing, but organisation of material is essential. What is the arc of the book? One can use the established narrative techniques that fiction uses – setting up a conundrum, followed by conflict and a resolution – except that this is likely to be argued intellectually rather than treated metaphorically or dramatically.

Set the scene and give context and don’t be afraid of employing the five senses. Establish which person you are going to use – first, second or third – and basically stick to it, except when switching to another person aids understanding.

Use the active voice whenever possible because it creates more interest. “The passive can be boring,” says Pushpinder Khaneka, author of Read The World. “You need to vary it. Be careful not to let the writing become too prosaic. Keep it lively.” Good non-fiction still tells a story, even if it’s on a topic like business or science. Dialogue adds life, too.

Yet the passive is a vital tool in explaining process and is used extensively in manuals and textbooks. It works when the reliability of the imparted information outweighs any entertainment value. As always, it’s a balance.

Everyone is different and obviously there’s no right or wrong way to construct a piece of writing. Some will strongly recommend finishing the research before putting pen to paper. I broke the rules in this regard with my biography. When I unearthed some shocking secrets about my grandfather, it turned my book on its head and it became a different beast. But, as I was also a character in the narrative, I was able to exploit this unforeseen drama.

Notes are your armoury at this stage. These jottings should eventually morph into the beginnings of a structure. The narrative will have chapter headings, sub-headings and sub-points. A family tree-type diagram or a mind map may assist in seeing the overall shape. Then you have to decide the order in which the different sections appear. Chopping and changing is a natural part of the process.

When I turned to writing books, I found it impossible to throw off what I’d learnt in my years as a journalist. And, contrary to what some people may regard as literature’s Wild West, writing for the media is incredibly disciplined and controlled, not least as far as technique is concerned. There’s always an editor sitting on my shoulder, checking everything I write.

My degree in English literature meant the sentences I wrote for my first local rag, the East Grinstead Observer (a tabloid), were too long. My editor called me in and told me that the absolute top limit for the number of words in a sentence was 25 but I should aim for 18 on average. And they should be simple. Avoid jargon: just because you use specialist language doesn’t mean anyone else will understand it. And, he said, never expect anyone to read a sentence twice; they should get it first time.

If only it was all that simple. In reality, the boundaries between fiction and non-fiction are continually blurred, especially with biography. “If we think of truth as something of granite-like solidity and of personality as something of rainbow-like intangibility and reflect that the aim of biography is to weld these two into one seamless whole, we shall admit that the problem is a stiff one and that we need not wonder if biographers, for the most part, failed to solve it.” So says Virginia Woolf.

One modern author who embraces the world of what is known as ‘faction’ is Richard C. McNeff. “My Aleister Crowley spy series operates in a hybrid realm between fact and fiction, exploring the tantalising might-have-beens of real events and lives. Plausibility is vital, however. Contrast The Crown, widely derided for demonstrable falsehoods, with Mr Bates vs The Post Office, whose honesty produced such a heartening response.”

Rules are there for a purpose. But bending them may turn a competent piece of work into a masterpiece. Or, equally, a disaster. As ever, it’s whatever works best.

Editing

However skilled the writer, careful proof reading and editing are required. The first round should be done by the author and cutting extraneous material is a central part of this. Historian Mark Gorman describes himself as ruthless in this regard, having cut the manuscript of Saving The People’s Forest from 100,000 words to 60,000. “It’s a very bracing exercise,” he comments.

Editing by another pair of eyes is just as important. “A good editor can pick up on inconsistencies of style,” says John Walker, author of Out Of Sight, Out Of Mind, the history of a notorious London workhouse. “I found my editor on Reedsy and she brought fresh vision and picked up things I hadn’t because I was too close to my material.”

In our world of echo chambers, cancel culture and political polarisation, reasonableness is often left stranded, mute and impotent. Good non-fiction writers can step in – indeed they must step in – and occupy that vacuum, filling the space with reliability and balance. Oh yes, and good old facts. Remember those?

Robert Nurden’s latest book, I Always Wanted To Be A Dad: Men Without Children is available on Amazon or from his website: robertnurden.com

You an also find Robert on Facebook: @robert.nurden

Comments