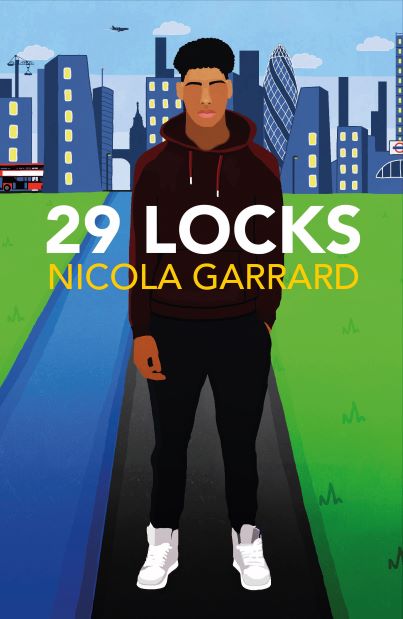

In her latest post for Writers & Artists about the experience of publishing her debut novel, Nicola Garrard provides insight into working with an independent publisher and, in particular, the process of working with an editor.

“To write is human, to edit divine.”

Stephen King, On Writing

As 29 LOCKS began to be edited, copyedited and proofread in the run up to publication, the enormity of what was happening dawned. A team of professionals had taken on my story, applying their skills and experience so that it would meet the high expectations of readers.

My publisher, Rosemarie Hudson of HopeRoad, assigned Joan Deitch to edit 29 LOCKS. Before meeting Joan, I steeled myself to sound passably intelligent in the presence of a stern grammarian, feeling like a child sent to the headteacher’s office. She had the fierce literary intelligence I’d expected, but her editorial divinity (to paraphrase King) was demonstrated in more surprising ways: kindness, praise and a genuine engagement in the complex social issues my novel tackles. I learned, quite by accident, having re-read Brixton Rock at the time of McQueen’s Small Axe series, that she had been Alex Wheatle’s editor, so I knew she would understand my protagonist’s world and the London dialect in which he tells his story.

Working with Joan was an education in kindness. She often boosted my confidence, writing ‘I’m enjoying it even more now, third time around. It’s got some mind-blowing scenes,’ and, ‘I had a quick look at the end and of course I had tears in my eyes immediately.’ Knowing how writers anxiously refresh their emails, she would check in with timings: ‘I’ve been going through the novel and in fact am on my last go-through: I should be finished by the weekend and be emailing it back to you.’

But ultimately, the role of an editor is to advocate for the reader against the ego of the writer. Joan’s talent was a fine-tuned sensitivity to the precise moments where the reader might awake from their dream-state to ask the wrong kind of question and identify prose that triggers the reader’s off-switch. Like a good teacher, Joan was a master of the face-saving phrase: ‘instinct says to avoid…’, ‘Have a ponder and if you hate the idea as being totally unsuitable, there’s no harm done’ and explained why changes would make the reading experience easier.

I’d expected to kill a few darlings so I kept a version of my manuscript as a ‘writer’s cut’, full of swearing and indulgent poetic flights – for my eyes only. I think of the novel going out in June as the ‘publisher’s cut’, its edges knocked off by the editorial process. From the very beginning, I promised myself I would embrace all Joan’s suggestions, including restructuring the novel’s non-chronological order into a linear one and adding a note of hope to the ending, knowing that her advice came from a deep well of experience. The novel is now better than ever, free of writer’s ego and ready for readers.

Some changes were harder than others, though. My experience working with young people taught me that my 15 year-old protagonist would barely notice the swearing that peppered his story. Percussive and comic, swear words exist in the voice of some teenagers as an integral part of their communication. My fifth blog in this series describes meeting some of the sweary teenagers who inspired my novel and how they had charmed me. Without this natural voice, I worried the protagonist’s casually violent world would be sanitised, yet I had agreed with the publisher to lower the target readership from 16+ to 14+, a process not unlike cutting a BBFC-certificated film from 15 to 12.

As a parent and teacher, I largely dislike swearing in YA fiction, as do many school librarians, and since teenagers rarely buy books, writers of contemporary YA fiction must compromise between authenticity and the duty of care to young readers parents expect. My original draft – the one shortlisted by the Lucy Cavendish Fiction Award and Mslexia’s Children’s Novel Competition – had around 60 instances of swearing and degrading language over 75,000 words. They stuck out like sore thumbs and left intact, teachers like me would hesitate to support the book, despite its allure for reluctant teenage readers. In its final state, offensive swearing, such as the F word, was replaced with milder expressions. It is now a book parents and teachers will want young people to read, and as such is better placed to challenge damaging stereotypes of gang- and poverty-affected teenagers and celebrate their resilience and wit.

The final part of the editorial process is proofreading. HopeRoad’s talented proofreader, Charles Phillips did a remarkable job of finding esoteric errors, such as a South London convenience store’s change of name after 2001. He also saved my future blushes in schools by spotting I’d misnamed a football trick which would have revealed me for the sports fraud I have always been.

The experience of being edited has been enriching. As I work on my current WIP, I try to remember what I have learned, from signalling the passing of time and the use of em-dashes and ellipses, to the importance of keeping things simple and considering the reader’s experience.

Next time I work with an editor, I may not feel like a child sent into the headteacher’s office, but I will retain my reverence and gratitude for their precise and patient work, and I will treasure my experience with Joan and the email in which she wrote, ‘The moments of sheer beauty, shock and pathos in this novel have caused me many times to catch my breath. Rosemarie and I believe in it wholeheartedly.’

Next time, Part 3: Working with a Publicist

Pre-order 29 LOCKS at hoperoadpublishing.com/29-locks

Nicola Garrard has taught English in secondary schools for twenty-three years, including fifteen years at an inner-city London comprehensive. She was a runner up in the Poetry Book Society poetry competition, judged by one of her heroes, Carol Ann Duffy. Her words have been published in Mslexia Magazine, the IRON Book of Trees and the Writers’ & Artists’ Yearbook. She lives in Sussex with her family and a Jack Russell terrier called Little Bear. Her favourite things about being a teacher are not found in classrooms but on school trips to wild places: capsizing canoes in icy lakes and getting lost in the mountains. Young people always find the way home. nicola-garrard.co.uk

Comments