Author August Thompson shares the essential elements he kept in mind while writing a coming-of-age story.

The coming-of-age novel is a mainstay of literature. It’s a format that has defined generations, yet, unfortunately, now risks feeling stale.

This staleness comes from adoration; the coming-of-age novel’s timelessness is both its gift and its curse. At this point, we have libraries full of coming-of-age novels, and many readers are shaped permanently by their favorite coming-of-age story.

It’s a complex thing to complain about the tropes of a coming-of-age novel, because, like all clichés, they are clichés for a reason. They are moments directly boosted from the transformative moments of a person’s young life and novelists attempt to crystalize these memories that feel like pure light. First love, first loss, first time away from home. Almost everyone has some form of experience like these.

A writer’s job is often to both create a familiar feeling in a reader and to subvert it at the same time. Make the expected the unexpected. The alchemy of how to do this is vague, complex, and often head-smashingly frustrating, but in terms of writing a coming-of-age story, there are ways one can be proactive in their writing process to create a fresh reading experience.

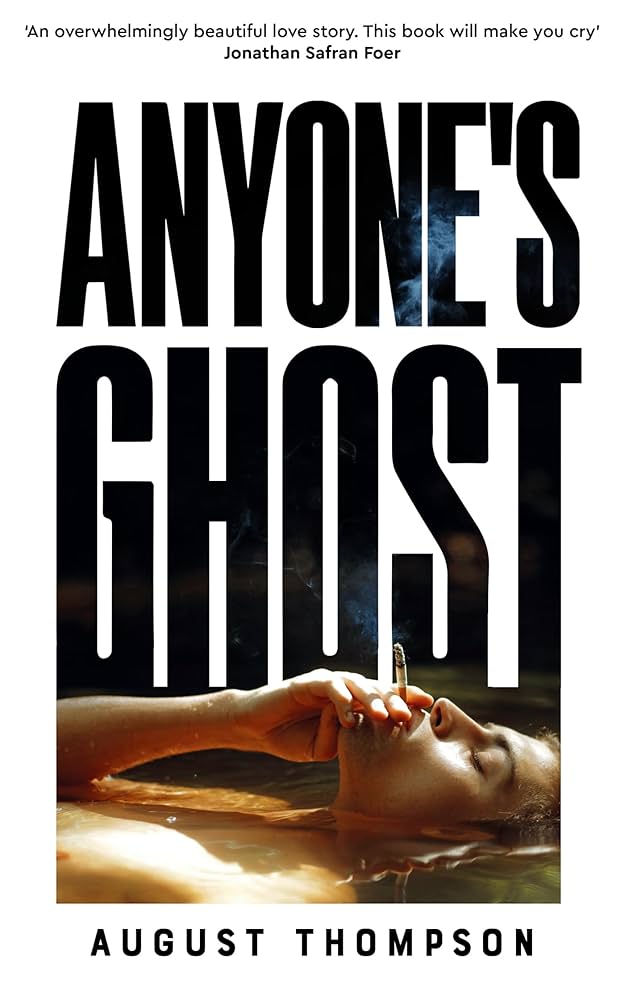

When writing my novel, Anyone’s Ghost, these are a few things I kept in mind:

Choose a unique setting

Anyone’s Ghost is set, mainly, in rural New Hampshire and the East Side of Manhattan. The former is rarely portrayed in American literature, let alone fiction from the UK. It’s a strange and gorgeous place, plush with bizarro Americana (giant mini-golf courses, waterslides the size of rivers) and natural beauty.

It’s where I’m from, which made it easier to write about, but even if it wasn’t it was the ideal setting for two boys trying to find freedom in restrictive masculinity. The locale has natural set-pieces built in—the world’s largest arcade, for example—and the local politics (New Hampshire is a very libertarian state) helped create a friction that lent itself to the story easily, as the state claims to be individualistic but still has terms for what the “right kind” of individualism looks like.

Try to find a place that is unique—scenically, thematically, feel-wise—and set your story there.

If that’s simply impossible, there are ways to make more-familiar locations exciting. The second part of my novel is set in Manhattan. There have been, conservatively, ten-million novels set in New York City as some 90% of writers seem to live here. I was extremely conscious of how to avoid writing just-another-NYC novel.

I chose to set the New York section during a blackout caused by Hurricane Sandy in 2012. That let the standard feel new. The city overlaid by new shadows, the people finding strange unities in the face of overwhelming newness.

- Write what you know, selectively

One’s overall life is filled with interesting details, whereas one’s day-to-day life is, usually, extremely boring. Realist writers have a responsibility to make sure their stories find the average of the two.

A good writer can mine a lifetime of little details and anecdotes and observations and compress them into three-hundred pages. Don’t be overly loyal to telling things like they were. Instead, manipulate time. Move between the most interesting parts deftly. Cut out the dutiful parts of life, even if it feels less realistic.

Focus on the drama

I always get asked if my novel is autobiographical. It’s a natural impulse and one that is often supported by how books are marketed—namely, readers like connecting the writer to their work because it adds a level of authenticity and relatability.Unfortunately for me, my adolescence was largely drab. I was a dweeb in high school and had few moments of romance. What I focused on in Anyone’s Ghost was how to turn all of the feelings that dominated my youth—yearning, pining, and joy— into scenes. Focusing on how to dramatize one’s sensibilities is a way to create characters that act naturally.

Almost none of the book is true, but that helped the story feel truer.

- Embrace surprise

My novel has four main characters, in essence. Theron, our narrator, Jake, the lifeforce of the novel, Theron’s Dad, gruff, difficult and an odd sort of loving, and Lou, the other object of affection, and Theron’s longtime girlfriend.

When I originally planned the novel, there was no Lou. I wrote the first third without her in mind at all. She came into being out of necessity—simply, I needed Theron to have someone to talk to during a scene early in part 2 of the novel. But once I started writing Lou, I realized she was the key to making the novel so much more than it could have been. She added a new dramatic triangulation and an opportunity to approach a much more complicated form of queerness. Maybe most importantly, she offered a way to write about how one can be in love with more than one person at a time.

Lou’s arrival—if the reader will allow me to talk so loftily about a character of my own creation—was completely unexpected, but helped make the novel what it is. I had to eradicate my idea of what the book was and allow surprise to take me somewhere new, somewhere I was afraid of. Thank god for that. One should never write a novel while daunted.

August Thompson was born and raised in the middle of nowhere, New Hampshire, before he attended middle school in West LA. After surviving California optimism, he moved to NYC for his bachelor’s, studied in Berlin, and taught English in Spain for two years. He recently received his MFA at New York University’s creative writing program as a Goldwater Fellow.

Comments