Aspiring writers are bombarded with advice about what makes good writing. A Google search for ‘writing rules’ returns a host of forthright (and sometimes contradictory) opinions from the likes of Stephen King, Elmore Leonard, George Orwell and Neil Gaiman, and that’s just on the first page. It can be hard to know which to disregard and which to add to your writer’s toolkit.

Many of the familiar tropes – show don’t tell, avoid adjectives and adverbs, write what you know – are founded in truth and can help build the foundations of good writing practice no matter what the genre, but how do they apply to historical fiction?

The difference between showing and telling has been written about endlessly, so I won’t go over the concept here. Instead, let’s look at how both can be useful in the context of creating a convincing historical world.

When we set a story in the past we inevitably have to create and inhabit unfamiliar surroundings. Using sensory information can help create the physical environment. What do things look, smell and taste like? We can show this through the immediate actions and reactions of our characters. Instead of telling us that the meal tasted bad, show us by having your character retch at the smell of maggot-infested meat or spit out a mouthful of food, despite their grumbling belly. Infuse these actions with only the sensory details that your characters would notice. The stuff of everyday life would pass without comment, so be sparing. A few carefully chosen words will give flavour – leave room for your readers to imagine the rest.

A tougher challenge is dealing with the internal world of our characters, with cultural beliefs and attitudes that might seem alien to a modern reader. As a writer it’s tempting to give characters our own sensibilities. I’ve written about women in a pre-feminist world when accepted attitudes to women’s roles were very different from today. It might be hard to root for a woman who accepts her subjugated position or who doesn’t question her husband’s superior one. We need to understand her emotional world. Using the tool of showing can help us understand and empathise with a character’s motivations, even when they seem inexplicable.

Using direct actions can be really effective here. Show beliefs, attitudes and emotions through interactions, reactions and dialogue. Conversation can be a great way to convey contentious issues while still progressing the story. Much of a character’s interior world and belief system might be unspoken but you need to know what’s going on beneath the surface and give them consistent actions. Readers will understand without the need to be explicit.

There are times when telling works too; sometimes it’s essential. One of the mistakes that many new historical writers make is recounting too much historical fact. We’ve all read those books with superfluous paragraphs, weighted down with research. I think this is partly due to pressure to prove you know your stuff and partly because there’s so much interesting historical detail it’s tempting to include it all. We’ve all been guilty of clinging onto that gem we found fascinating but isn’t really necessary for the story.

But sometimes telling can be used to move the story along or to give information that doesn’t fit easily into a scene. A frequent challenge is how to inform your readers of events that happen off-screen, especially tricky when writing in first person. It’s unlikely your character will be manning the guns on every battlefield, or attending in every birth chamber and there are only so many times we can use the erstwhile messenger, arriving just in time to impart some pivotal nugget of history.

It’s helpful to think about how news would have spread in your period. How long would it have taken? Is there a way you can show us the event through character action or direct experience? If not, sometimes telling works just as well, keeping the story moving and cutting out a lot of extra baggage.

Linked to the showing/telling idea is the common advice to avoid adjectives and adverbs. Judicious use of both can be extremely effective – a perfectly placed adjective can do a lot to conjure historical atmosphere. But choose your descriptive words carefully. Metaphors and similes should be of the time. If you’re writing from the point of view of a lady in the Tudor court, a rose probably shouldn’t be ‘pillar box red’ or ‘sweet scented as cotton candy’.

Avoiding obvious anachronisms should be easy but there are lots of words that might seem out of place out to others (as I found out when my first novel was copy-edited). If you’re not sure about using a word seek another opinion and check the etymology. There are some great online tools and dictionaries to help with this. But – a word of warning – don’t get too bogged down in the detail. Just because we don’t have recorded evidence of a word until fifty or a hundred years after your character wants to say it doesn’t mean it wasn’t used in everyday speech. Use your judgment. If it sticks out like a sore thumb to you or someone else, it probably needs to be changed.

Which brings me to that old cliché: ‘write what you know’. How can we do this when we’re creating worlds so far outside of our experience, writing about gladiators in Ancient Rome or a young stowaway on an 18th century pirate ship?

Obviously, this is where research comes in. We can steep ourselves in the practical and domestic details of the period. We can familiarise ourselves with the culture. We can make research trips, read books and scour the internet. I do think we need to know a lot more background information than will ever go into the books we write. We can recreate and reimagine but we can never really know what life was like back then.

What we do know is the bit that doesn’t change – the experience of being human. You might not have faced down a hungry lion in the Colosseum but you know how it feels to be afraid; you might never have sought adventure on the high seas, but you know how it feels to be a teenager and how it feels to take risks. You’ve already experienced, grief, loss, sorrow and failure (if you’re attempting a novel you’ve almost certainly known some of these!) and – I hope – you’ve known triumph, joy, desire and how it feels to fall in love. These are the things you know: timeless emotional truths that will make your characters come alive.

And in the end that’s what makes any writing engaging and enduring – we can tell the stories of those who came before us and pepper our books with historical facts, but ultimately, it’s the emotional journey of our characters that hooks us in and keeps us turning the page.

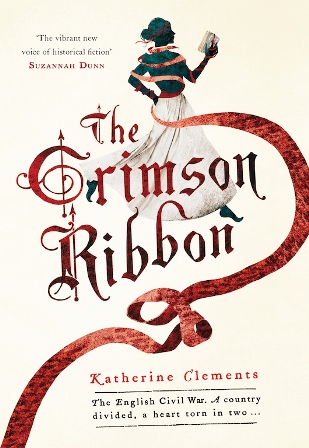

Katherine writes historical novels set in the 17th century. Her critically acclaimed debut, The Crimson Ribbon, was published in 2014 and her second, The Silvered Heart, is out now. She has enjoyed success with her short stories and won a Historical Short Story Competition sponsored by Jerwood in 2012. She has had a varied career, working in media, the charity sector and education. Most recently she worked for a national examination board, where she led the development and launch of the UK’s first A level in Creative Writing. She currently lives in Manchester where she writes full time. Katherine is also editor of Historia, the magazine of the Historical Writers’ Association. Follow her on Twitter here and find her on Facebook here.

Comments