Women are something of a rarity in history – shy, domestic creatures who peep out between the cracks of their husband’s ‘greater’ deeds. If we believe the historians of their day, they were there to look pretty and to provide care and admiration and, of course, heirs. This, however, cannot be the whole story and that is why I chose to write my trilogy, The Queens of the Conquest, about the women fighting to be Queen of England in 1066. Not that I don’t like the men – I’m a little bit in love with all my heroes – but theirs are the grand stories everyone knows and I was more interested in what happened behind the scenes of the battles. Exploring the female side of a previous era allows access to those more intimate stories, but it is not without problems.

The first is the paucity of information about women in times past, especially further back. This can be a huge frustration for the historian but it is something of a gift for the novelist as it allows scope to create a character. This, however, leads to the second and crucial problem – how to create a heroine who is believably of her time but to whom modern readers can still relate.

There is no way that women in the past could approach the world with the liberated, equal-opportunities attitude that we take today, yet throughout history there have been plenty of women with strong characters – Boadicea, Eleanor of Aquitaine, Elizabeth I to name just a few – who hopefully allow us to believe that it was possible to operate as an individual and not just as a secondary figure. So how do we create these engaging historical women? Here are a few key things to consider:

- Build a believable character. Look at your heroine’s world through her eyes and consider how that would inform the way she acts. With occasional exceptions, heroines are less likely to think they should be allowed to enter male preserves, than to be assertive within their own areas of power. Don’t let yourself be frustrated by what you might see as her limitations but, instead, exploit her strengths.

- Draw on the core traits of being human and of being a woman. Childbirth is a prime example. Yes, a labouring woman was in more danger in previous times, but in a normal birth very little inside her own body and head would have been different to how it is now. Sex is the same. Put two people in bed together and it makes little difference whether they are beneath a 21st century duvet, a Saxon fur, or a woollen blanket.

- Explore feelings. For me, the key to historical fiction is not when things happened as much as how they affected the lives of those they happened to and how they made them feel. There must be more inherent similarities between women then and now than differences and it would surely be arrogant of us to assume that emotions are a new invention? Just because infant mortality was higher, we cannot conclude that mothers didn’t love their children; or because disease, famine and war killed so many, they weren’t mourned; or because most marriages were arranged, people didn’t fall in love. Yes, the rules and restrictions on our historical heroine’s lives would have been different but that’s what can create a wonderful tension for the modern reader – as long as the core feelings are strong and engaging.

- Find the right voice. This is perhaps the hardest of all and there are two sides to it. The first is the way that the characters speak and on the whole I feel that archaisms should be avoided in favour of a straightforward, relatively formal English. The second side is the narratorial voice and this can be tricky to get right. Metaphors need to be of their time. Some words can be tricky (you cannot, for example, do something ‘automatically’ before the invention of the ‘automaton’ in the 18th century). And the attitude of the writer, as well as that of her heroine, must fit the era, notably with a quiet awareness that her story is pre-feminism.

In the end, as with all fiction, it comes down to knowing our heroine inside out. We must research all we can about what makes her different from us - what she would have worn, how she would have washed, arranged her hair, cooked, or instructed others to cook. But then we must explore all the things that make her the same - how she feels about her life, what scares her, what thrills her, who she loves. Only once we know all this can we inhabit her world and create her story.

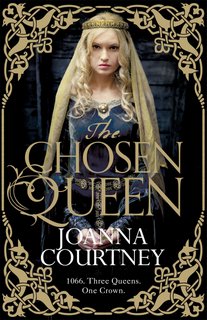

Ever since Joanna sat up in her cot with a book, she’s wanted to be a writer. She’s had over 200 stories and serials published in women’s magazines and has battled for years to make it as a novelist. She’s therefore delighted that Pan Macmillan have now published The Chosen Queen, the first of her historical trilogy, The Queens of the Conquest, telling the stories of the too-long-neglected women of 1066.

Comments