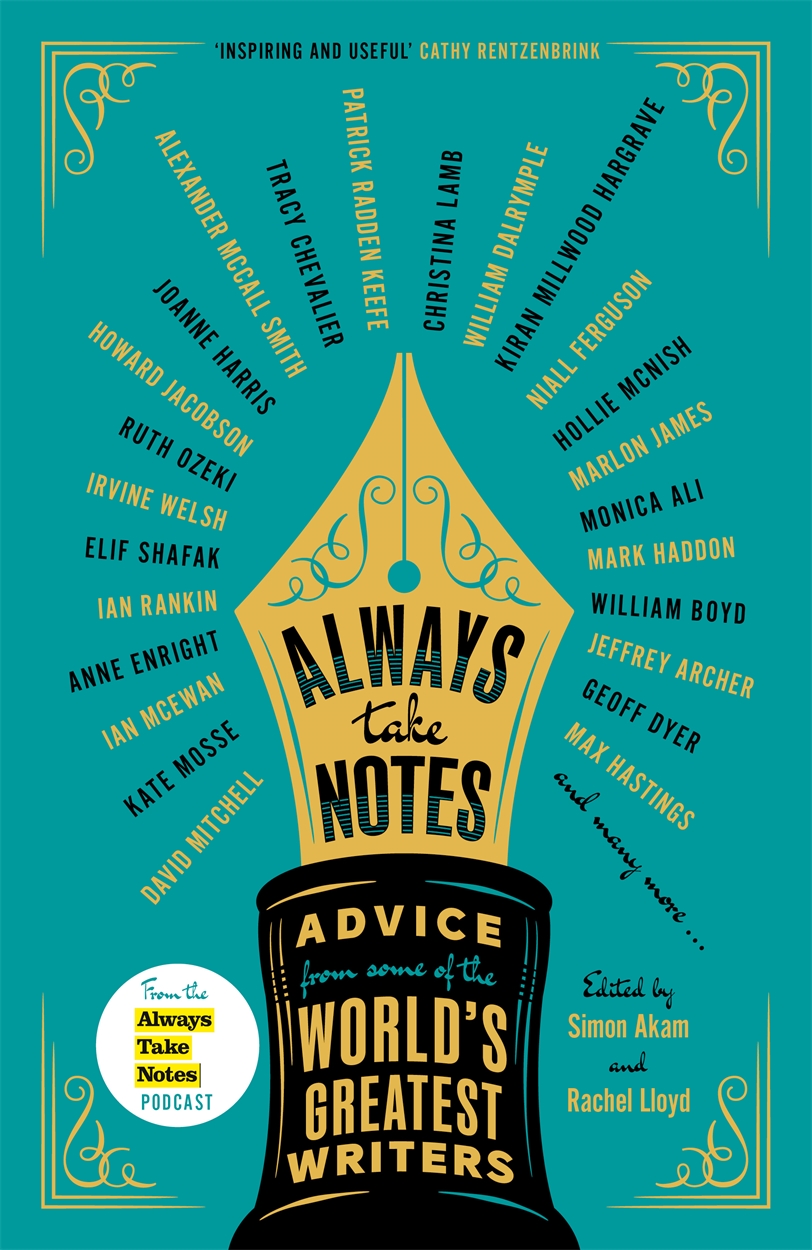

The Always Take Notes book is a compilation of writing advice from great authors, based on the popular podcast of the same name, hosted by journalists Rachel Lloyd and Simon Akam. In this exclusive extract, we hear from authors Tessa Hadley and David Mitchell on dealing with failure and rejection.

Every writer has failed at some point in their career. The failure may have been small: bungling a scene or turning out a clumsy phrase. Or it may be something that feels a lot more consequential – maybe you sent your writing off to an agent or publisher and never received a response, or you find yourself with a bad case of writer’s block.

A working day can feel like a failure if you haven’t hit your word count or have spent more time answering emails than immersed in your project. Procrastination has long been a problem for many writers: even Charles Dickens found writing a constant exercise in restlessness and frustration. Producing Little Dorrit involved ‘prowling about the rooms, sitting down, getting up, stirring the fire, looking out the window, teasing my hair, sitting down to write, writing nothing, writing something and tearing it up, going out, coming in, a Monster to my family, a dread Phenomenon to myself.’

Tessa Hadley, novelist and short-story writer

I do definitely have a sense of why [publishers] passed on early books - I think because they were awful. They were right. To flatter myself, I would like to think there’s a funny kind of awful that happens when, one day, maybe, you will be able to do it, but you’re not halfway there. You’re really catastrophically failing to do the thing that maybe, one day, you find a way of doing.

I think I was trying to write other people’s books. I was still in a very submissive, admiring and worshipping phase as a reader. I was reading far too many classics and not enough contemporary fiction. If I was reading contemporaries, I was reading Nadine Gordimer and thinking, “Well, I’ll try and write a great novel, like her novels of the apartheid era in South Africa, but I’ll set it in South Wales,’ where I was then living and do live again now. So there was some unspeakable novel about the miners’ strike, which I’m glad is now rotted down in landfill. It wasn’t me. I wasn’t saying what I thought - I was saying what I thought someone else should write.

In the moments when I did finally start putting down the first sentences that were true, to some extent, it was in accepting that the terrain was small. It was what it was: it was my world, not my life, but my world. I can remember some of the first sentences I wrote that felt true - [they] were about a woman visiting Cardiff Museum with a child in a wheelchair. That was not directly connected to my life, but somehow, something in there clicked. I was fully me, utilising what I thought about things, what I had to say. I recognised the sound of myself. But that took a long time – there were about four awful, effortful, goody-good novels before that.

David Mitchell, novelist

Pretty much every time I write a novel, I fail about 50 pages in. I thought this was going to be great; I had this image in my head about how this was going to be the best damn thing I’ve ever written. And oh my lord, look at this sorry, gobbling vomity mess of a pile I’ve got here.

That feeling’s good news. That your ally. Most of it’s right, but something’s wrong. Often there’s something in it that you don’t want to give up – you're right, there’s nothing wrong with it, it’s a great idea. It just doesn’t belong in this book and you’ve got to kiss it goodbye. You reboot at that point and you think, ‘Okay, I’ve got to get rid of that. What bits do I really like now and, actually, who is this story about? Who is it really? I thought it was about this, but it’s clearly not. So who and what is it about?' Give yourself that licence to go wrong, because I think you usually have to.

Comments