Non-fiction author Michael Lackey explores the biographical novel; why it's one of the richest and most surprising aesthetic forms of contemporary literature and why it's a genre we're only just beginning to understand and appreciate.

In a 1968 forum about the uses of history in the novel, Ralph Ellison praised Robert Penn Warren for changing the name of Huey Long to Willie Stark in his novel All the King’s Men. According to Ellison, this choice enabled Warren to use the Stark character to symbolize and therefore critique a pervasive psychology among modern politicians. By stark contrast, Ellison faulted William Styron for not changing the name of the protagonist in The Confessions of Nat Turner. Ellison considered Styron’s choice a mistake for two separate reasons: it made him vulnerable to criticism from historians and it rendered his protagonist, because of its historical specificity, incapable of functioning as a symbolic instrument of sociopolitical critique.

Yet Ellison failed to understand the trajectory of contemporary literature, as the biographical novel has now become a dominant form. Michael Cunningham’s The Hours (Virginia Woolf), Joyce Carol Oates’ Blonde (Marilyn Monroe), Colm Tóibín’s The Master (Henry James), and Hilary Mantel’s Wolf Hall (Thomas Cromwell) are just a few stellar biographical novels that have captivated the reading public in recent years.

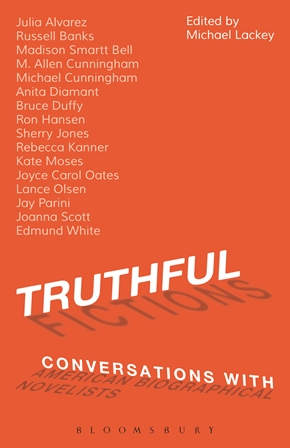

But what allowed these writers to take the liberty of naming their protagonists after the historical figures? What kind of sociopolitical critique, if any, can the biographical novel level? And what fictional techniques can and do biographical novelists deploy in their works? Such were the questions I had when I interviewed some of the most prominent biographical novelists in the United States for my book Truthful Fictions, and their answers give us considerable insight into the nature of artistic creation and contemporary fiction.

Perhaps the most striking thing I discovered was how and why contemporary writers convert historical figures into literary symbols. Oates told me that her characters are more interesting and complicated than the figures on which they are based. This is the case because they function to symbolize much more than just themselves. For instance, in her novel Blonde, Oates pictures the relationship between JFK and Marilyn Monroe, but she only refers to Kennedy as The President. This certainly makes sense if we know that Oates wrote the novel in the late nineties, at the height of the Bill Clinton/Monica Lewinsky scandal. Oates’ description of the JKF/Monroe affair bears a striking resemblance to the Clinton/Lewinsky affair, which enables Oates to suggest that there is a clear link between the patriarchal politics of JFK and Clinton: that JFK treated women in the 1960s the same way that Clinton did in the 1990s. Or, read the other way, we can use the Lewinsky/Clinton case to illuminate the Monroe/JFK affair.

Additionally, many contemporary writers root their fiction in historical fact because of skepticism about traditional literary symbols. The danger of the traditional fictional symbol is that an author could conveniently concoct one that would serve his or her ideological agenda, so a Virginia Woolf could create a Sir William Bradshaw to represent a pervasive patriarchal psychology in the English medical profession of the 1920s. This character as symbol may be extremely effective and even incredibly accurate, but contemporary biographical novelists want to avoid the charge of manufacturing an arbitrary symbol, so they base their characters on actual historical figures. But because they are novelists and not biographers, they also invent characters and scenes that represent the sociopolitical significance of their characters’ thinking and being.

It is this strategic blending of fact and fiction that has enabled contemporary biographical novelists to produce a rich literary form that engages and represents history and critiques culture and the political in new and innovative ways. For instance, what would happen if Virginia Woolf or Clarissa Dalloway were living in the 1950s or the 1990s? In The Hours, Michael Cunningham blends fact and fiction in order to answer precisely this question, as he told me in my interview with him.

One of the most fascinating developments in the contemporary biographical novel is the attempt to access the interior lives of gays and lesbians, which we see in stellar works such as Edmund White’s Hotel de Dream, Paul Russell’s The Unreal Life of Sergey Nabakov, and Russell Banks’ Cloudsplitter. There is no evidence that John Brown’s son, Owen, was gay, but Banks creates his character in this way nonetheless. When asked why he did this, he said that he had two separate reasons. First, he believes that ten percent of the population is gay, so it would be unrealistic for him to have a novel with many characters but no gay ones. Therefore, he decided to make Owen gay in order to give this demographic a voice in his work. Second, he thinks that racism and homophobia have created similar types of cultural pathology. Since our contemporary culture is struggling to come to terms with homosexuality, he thought he could combine the issues of race and sexuality in and through the protagonist of his novel. In essence, Banks believes that, while the biographical novel pictures the life of someone from the past, it is really about the present.

Insofar as contemporary fiction is concerned, the biographical novel is one of the richest and most surprising aesthetic forms. The best tell us much more than just a powerful story about a noteworthy person. For instance, we learn a great deal about the artist Egon Schiele from Joanna Scott’s Arrogance, but the novel tells us even more about modern politics and European art. We discover much of substance about the philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein from Bruce Duffy’s The World as I Found It, but the novel tells us even more about the condition of knowledge and philosophy in the early twentieth century. There have been a couple hundred biographical novels published over the last twenty years, but only now are we starting to understand and appreciate what this genre of fiction is uniquely capable of doing.

Michael Lackey is Associate Professor of English at the University of Minnesota, USA. He is the author of The Modernist God State: A Literary Study of the Nazis’ Christian Reich (2012), and African American Atheists and Political Liberation: A Study of the Socio-Cultural Dynamics of Faith, which won the Choice Award for Outstanding Academic Title in 2008. He is also the editor of The Haverford Discussions: A Black Integrationist Manifesto for Racial Justice (2013). - See more here.

Find out more about titles and buy the latest releases from Michael Lackey at Bloomsbury.com.

Comments