What are our experiences of true stories? Author So Mayer scrutinizes our own levels of reality when we're looking to distinguish between writing that's classified as 'fiction' or 'non-fiction'. Is it possible to have our cake and eat it?

The very last page of Ekow Eshun’s brilliant new book The Stranger: Five Extraordinary Black Men and the Worlds That Made Them contains what some readers might experience as a twist: there is a publisher’s note that states ‘The Strangers is a work of creative non-fiction… The book was inspired by the lives of real people.’

Keen film viewers will recognise the phrase ‘inspired by’, and may have taken note of the recent case in which Steve Coogan was successfully sued for libel over his portrayal of a real person in a film inspired by a true story – and that was a fiction film! It’s an example that reminds us the stakes are high whenever we are writing about the world and our perceptions of it, in whatever form or genre. As a survivor, I write creative non-fiction precisely because it is a form that raises, and requires that we raise, important questions about truth: who defines it, who has access to evidence, what forms and vocabularies are seen as truthful or trustworthy, and who and what gets excluded, dismissed or silenced.

Eshun opens The Strangers with a useful, thoughtful author’s note where he clearly defines his rigorous process:

The structure of my narrative has been guided by the factual details of each man’s biography but I have also given myself licence to conjure what the often limited archive cannot supply: the tone and texture of their inner lives.

There are two striking words close together in Eshun’s short statement that both relate to what is at stake in writing creative non-fiction: ‘licence’ and ‘conjure’. Conjure is a word that many people might associate with forms of trickery and magic, which is how some suspicious people think of all persuasive or creative writing! Conjure here might specifically conjure a resonance of Afro-Caribbean spiritual practice, conjure traditions that resisted slavery and empowered survival by remembering that another world was possible. This is a profound reminder of the dimensions we engage when we write. On the other hand, licence is a legal contract that grants rights and responsibilities. It’s a reminder of those legal issues such as libel, but more importantly of the contract with our reader, which we negotiate with every sentence to show that they can trust what we say.

Some people see creative non-fiction as a tricksy form that allows you to have your cake and eat it – and I don’t disagree. But I think more importantly, it is a form that asks you to bake the cake from scratch, having worked out the ingredients and recipe for yourself by trial and error! It asks you to determine what you think is licence(d) and what you think is conjure(d), what you believe in and where it sits in your writing: in the genre, in the address, in the structure? Where and how do you create the mutual contract with your reader so you can enjoy the cake together? It’s not just about baking the cake, but about cutting down through the layers to understand your own apprehension of truth and reality, and where that’s come from: school? TV? Dreams? Whether you write non-fiction or not, this is a great exercise for working on voice, narration and distribution of information in any genre – but it is not a piece of cake.

Compared to writing fiction or genres of non-fiction like biography and history, there are far fewer fixed guidelines on what creative non-fiction looks like — but in a conversation with fellow genre-hybridist Teju Cole for BOMB magazine, Aleksandar Hemon notes that:

In Bosnian, there are no words that are equivalent to ‘fiction’ and ‘nonfiction’, or that convey the distinction between them. This is not to say that there is no truth or falsehood. Rather, the stress is on storytelling. The closest translation of nonfiction would really be ‘true stories’.

There’s many great contemporary writers who write ‘true stories’, and in doing so, model how to investigate our own feelings about where truth resides and how best to put it into words. As Roxane Gay notes in her introduction to Selected Works of Audre Lorde, ‘the best writing reminds us that truth is complex and subjective’. Writers like Lorde and Gay model for us how braiding testimony and theory, documentary evidence and inner experience, demands all of our craft as writers.

I find that weaving in citations from writers and thinkers whose work aligns with yours is a powerful method for building confidence, both in your own vision of the levels of reality, and that that vision will be shared by your readers. This is particularly effective because creative non-fiction is increasingly a form used by writers whose voices and communities have been marginalised by and in dominant histories and documents, creating a respectful, rigorous conversation about how we define the truth of our own ‘true stories’ together, by listening to each other. Grab a fork and dig in.

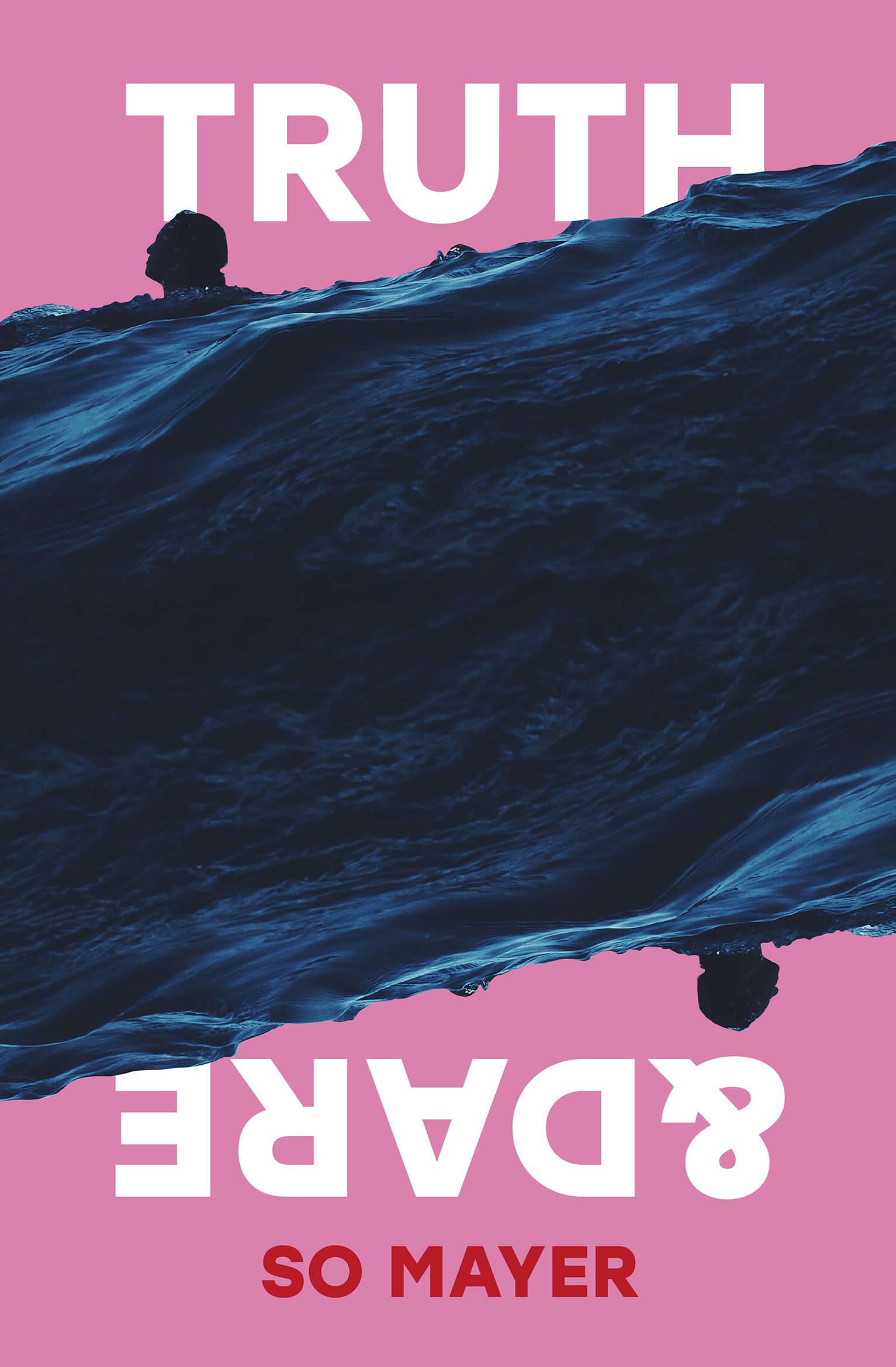

So Mayer is a writer, publisher, bookseller, organiser and film curator. Their first collection of speculative fiction and creative non-fiction Truth and Dare is out now from Cipher Press, and was longlisted for the 2024 Republic of Consciousness Prize, and A Nazi Word for a Nazi Thing, a book-length essay on queer films, bodies and fascism was published by Peninsula Press in 2020. Their recent collaborative projects are essay and short story collection Space Crone by Ursula K. Le Guin (Silver Press), winner of the 2024 Locus Award for Non-Fiction; speculative history podcast The Film We Can’t See (BBC Sounds); Unreal Sex (Cipher Press), and the critical anthology Mothers of Invention: Film, Media and Caregiving Labor. So works with Silver Press, Burley Fisher Books and queer feminist film curation collective Club Des Femmes.

So Mayer is a writer, publisher, bookseller, organiser and film curator. Their first collection of speculative fiction and creative non-fiction Truth and Dare is out now from Cipher Press, and was longlisted for the 2024 Republic of Consciousness Prize, and A Nazi Word for a Nazi Thing, a book-length essay on queer films, bodies and fascism was published by Peninsula Press in 2020. Their recent collaborative projects are essay and short story collection Space Crone by Ursula K. Le Guin (Silver Press), winner of the 2024 Locus Award for Non-Fiction; speculative history podcast The Film We Can’t See (BBC Sounds); Unreal Sex (Cipher Press), and the critical anthology Mothers of Invention: Film, Media and Caregiving Labor. So works with Silver Press, Burley Fisher Books and queer feminist film curation collective Club Des Femmes.

Website: somayer.net | Twitter: @Such_Mayer

Comments