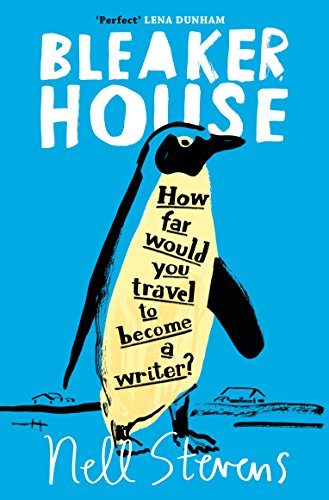

Nell Stevens shares essential tips on how NOT to write a novel...

Escape to a remote place

As a permanently-distracted, city-dwelling twenty-seven-year-old, I decided that the key to writing my first novel would be to take myself as far as possible away from friends, family and a functioning internet connection. I set off for Bleaker Island, a windswept, isolated island on the outskirts of the Falklands. I was optimistic that its marshes, cliffs and wide, white beach would be the perfect backdrop to my creative activities. Except that on Bleaker Island there was nobody to bounce ideas off, no films or talks or art from which to draw inspiration, nothing to do to let off steam after a day’s writing—all, it turned out, as crucial to the writing process as alone-time at a desk.

Start writing straight away

There’s something very daunting about a blank page. The temptation is to get rid of it as soon as possible by filling it with words – any words. And while getting warmed up is useful, it’s important to distinguish between the scribblings of a writer limbering up and the novel they want to write. On the island, I began writing my novel at speed, armed with only the flimsiest of plans. And the higher the word-count rose, the more secure I felt. But starting too soon can be a kind of cheating. The reason the blank page is terrifying is because it’s an invitation to think, deeply and carefully, about what you want to write on it. You can’t rush that alarming, unmoored stage. It’s when your ideas take shape.

Write a set number of words a day

I have always been a greedy reader of descriptions of writers’ routines: what time of day they work best, what they eat for breakfast. A staple of this genre is the detail about a writer’s daily word count: Graham Greene’s was 500; Ray Bradbury’s 1000. It is comforting, reassuringly predictable, to think that if you write a set number of words each day, your novel will develop on time and in order, like a watered plant.

On Bleaker Island, since there really wasn’t anything else to do, I aimed for 2500. I stuck to it rigorously, but the flaw in the plan became apparent as I went on. Practice and dedication are important, but writing 2500 words a day doesn’t mean those words are any good. Sometimes it’s better to speak only when you have something to say.

Be disciplined in everything you do

Alongside my daily word counts, I pursued a regime of discipline in almost every other element of my time on the island: I monitored my sleep, my food, my exercise. I thought that the more disciplined I was as a person, the more disciplined I’d be as a writer. It turns out, though, that the elements of writing that take place away from the computer—daydreaming, idling, pondering—can’t be scheduled neatly on a timetable, and are as vital to the process as any number of words on a page.

Write as though your life depends on it

Your responsibility as a writer is to the story and the reader, not to yourself. I wanted the novel I was writing on Bleaker Island to justify the strange, uncomfortable journey I was on, to make up for the many years I’d spent trying and failing to be “a writer”. I wanted to be able to go home at the end of it with something to show for my time on Bleaker Island.

Those are not the intentions that make great art. No story can withstand that sort of pressure from its author. It’s true that writers all have ambitions and deadlines and bills to pay, but when you sit down to write, that cannot be at the forefront of your mind. The only thing that should depend on your writing is the story you are telling. It is no surprise that my novel failed and that I left the island empty-handed.

About a year after I got home, I began something new: a strange mishmash of memoir and fiction about my time on the island and the experiences that had come before it. It was an experiment, written quickly and playfully and with no expectation that anything would come of it. That experiment became Bleaker House, a book that was written on the sofa in my flat in Peckham, erratically and sporadically in between the joys and irritations of normal life, and so, fortunately, broke every one of the rules listed here.

Nell Stevens lives in London, where she lectures in Creative Writing at Goldsmiths University. She has a PhD in Victorian literature from King's College London, and an MFA in Fiction from Boston University. Her debut book Bleaker House was published in 2017 by Picador. It is part memoir, part travelogue and part story collection, exploring the narrow spaces between real life and fiction.

Comments