A certain mystique surrounds fiction writing, a romantic image of authors inspired only by the need to “sit down at a typewriter and bleed”. Less so if you’re a children’s non-fiction writer, like me, working out the best 50 words to describe a backhoe loader.

But perhaps non-fiction writers are born that way too. As future novelists drafted their first stories, eight-year-old me was recording holidays in books longer than the trips themselves. Aged 12, I penned a thrice-weekly magazine with a circulation of three. And at university, I lingered far longer in the student newspaper offices than the pub.

Today I write for children, who are quick to abandon a book if they are bored. Quite right too — children are born scientists, constantly experimenting to work out what deserves their attention. So to make science (or any topic) irresistible to children, you need to think like one. 140 books into my career, I’m an expert in thinking like an eight-year-old.

Few eight-year-olds want to read a dry list of facts. That’s why three-quarters of children make a beeline for YouTube rather than Wikipedia. While your research skills must be impeccable, the information you share in a non-fiction book is less important than the way that you share it.

Instead of listing facts about space, write a travel guide to the solar system, or make the page itself turn into a space rocket. Instead of listing facts about life cycles, give children instructions for saving local wildlife, or bring to life that favourite playground debate – which predator would win in a fight? Use your unique experience to make fresh connections and take your readers on a real world adventure.

Hooking your audience doesn’t end with a creative angle. Each page, paragraph and sentence must work hard to remain fresh and relevant to children who have a host of other ways to entertain and educate themselves.

As you delve into a topic, ask questions like an eight-year-old. Can ducks walk backwards? Could dogs swim in ice cream? How do rabbits know which way they are going as they dig underground? Hunt for nuggets of information that will surprise and delight.

In workshops I teach children to do this by asking them to think of the most boring topic they can. You’ll need some one-liners ready to deal with the hecklers who call out ‘literacy’. But most children come up with gems… such as dust. Sharpen those research skills, and within minutes you have micrometeorites and dander-chomping dust mites on the table. Now everyone is engaged.

Like any educator, non-fiction writers have a great opportunity. Your book could be a child’s first introduction to a topic, the one that inspires them to find out more about the world, and to change it.

Whether I’m writing a trade title that will be proudly plucked from a bookshop as a birthday present, or a reading scheme title that will spend ten years travelling in hundreds of book bags, my aim is the same – find out what’s exciting about a topic, and pass that excitement on.

This is what I love most about writing non-fiction – researching the weird and wonderful, digging out the most mind-boggling facts and explaining the world to children in a fresh way.

I may not be the next JK Rowling. But hit me with your Why? Why? Why? and I’ll always have the best (50-word) answer.

Isabel Thomas is a science writer and author of more than 140 non-fiction books for children. She has been shortlisted for the Royal Society Young People’s Book Prize, the ASE Science Book of the Year, and the Blue Peter Book Awards. Isabel also writes for children’s science magazine Whizz Pop Bang, and for outreach projects including www.dementiaexplained.org. She is a primary school governor and vlogs about early years and primary education for Oxford Owl. Say hello @raisingchimps or visit www.isabelthomas.co.uk

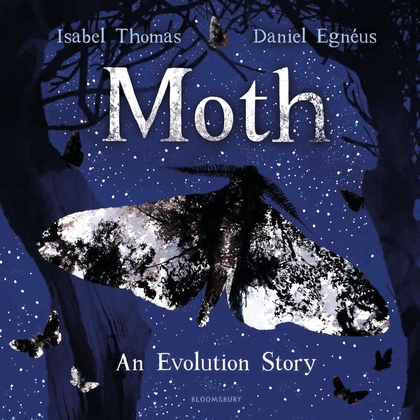

Isabel's latest title, Moth: An Evolution Story, is available to buy now.

Comments