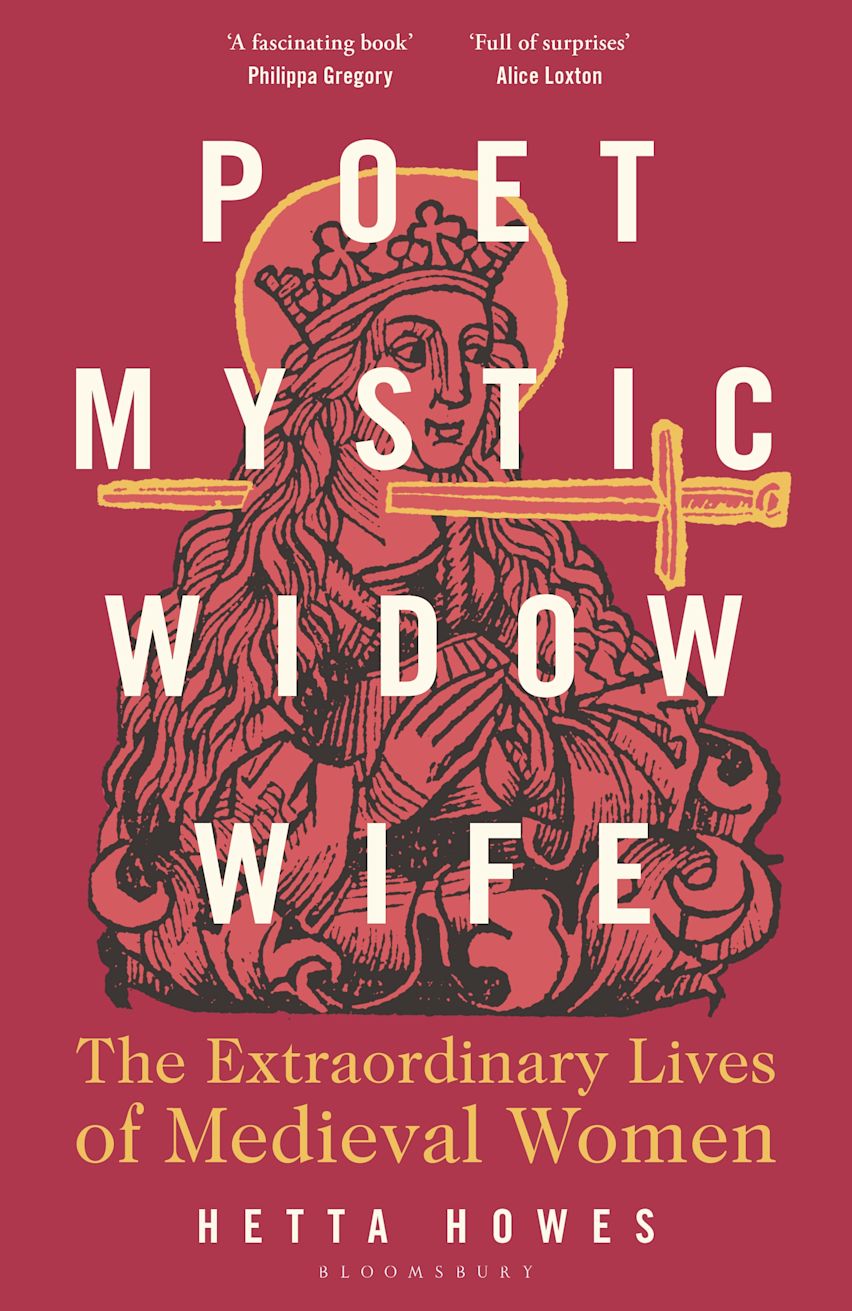

Academic and author Hetta Howes discuss the creation of Poet Mystic Widow Wife, her debut non-fiction book.

How long did it take you to research and write Poet Mystic Widow Wife?

In some ways, the research for Poet, Mystic, Widow, Wife began over ten years ago, when I was studying for my MA in Medieval Literature at Cambridge University. Since then, I’ve completed a PhD in medieval literature (specifically in fluid imagery in devotional writings by and for women) and taught many different university modules which include the writings of Marie de France, Julian of Norwich, Christine de Pizan and Margery Kempe. All this experience informed the book and made the writing process easier, as there was already a strong foundation to build on. However, there was inevitably lots of new research to undertake once the contract was secured and I kept researching and writing in tandem until the very end of the manuscript process.

I signed my contract in the summer of 2022 and submitted the final manuscript early in 2024, so in total the book took around two years. However, it’s difficult to quantify took in practical terms because I was juggling a lot of different commitments alongside completing the book - my day job as a university lecture, pregnancy symptoms and then maternity leave and family commitments. So, there were stretches of time when I was doing nothing but writing, and then a few months would go by without me doing any work on the book at all – most notably the first three months of my daughter’s life when I did absolutely nothing!

2. In the introduction, you mention how you discovered you were pregnant when writing this book, which has an eye-opening chapter on pregnancy and childbirth in medieval times. As a writer and researcher, how do you balance your work and your wellbeing?

This is tricky. I’ve always been a bit of a type A personality, and I also find it hard to say no to anything…so it’s no surprise that I struggle with balancing work and wellbeing! Since becoming a mum this has only become harder; it can be very difficult to carve out “me” time or rest of any kind. A good chunk of the book was written when my daughter was 4-9 months old and I felt constantly guilty – guilty if I wasn’t writing, guilty if I took time away from my daughter to write – and constantly tired. There are large swathes of Poet Mystic Widow Wife that I have little to no memory of writing. Now that she’s a bit older, the tiredness has become more manageable, but it’s still challenging trying to balance everything. My new year’s resolution is to try and schedule some time for myself every week (whether that’s doing some sort of exercise or just reading my book in bed) and to try and be content with “good enough” more often.

3. What was your favourite chapter to write and why?

I really enjoyed writing the chapter “Knocked Up”, on pregnancy and childbirth, largely because I wrote large chunks of it while pregnant and then revised and added to it after my daughter was born. When I was writing Poet Mystic Widow Wife, it was important to me to emphasise the points of connection between women in the twenty-first century and women living in the Middle Ages. Although the world of these writers looked completely different to our own in a myriad of ways, threads of connection still persist. For me, personally, pregnancy and childbirth became one of those threads. Sure, I’ve never had visions of God or overseen the production of a medieval manuscript; I’ve never voluntarily enclosed myself in a cell or presented my writing to royalty. But, like Margery Kempe and Christine de Pizan, I have experienced what it’s like to give birth and become a mother. And I structured my book around key life experiences in the hope that others might find their own threads of connection, whether that’s travelling the world, the struggle to have it all, creativity, love, loneliness, friendship, death… the list goes on! It was also really exciting to try and get inside the medieval birth chamber, a space that is usually shrouded in secrecy, and to try and bring it to life for the readers.

4. What advice would you have for writers from an academic background who’d like to write a non-fiction book that appeals to the general reader? What would your tips be on making years of deep, intense research accessible?

A trade book is a tricky beast. You want it to be as accessible as possible, and to appeal to as many readers as possible, but you also don’t want to “dumb things down” - readers are always discerning enough to spot this and be put off by it (rightly so) and it also does a disservice to the material. It’s a fine line to tread. My best advice would be to keep storytelling front and centre. Ultimately, academic research is storytelling, it’s just packaged very differently to non-fiction. If you can figure out a way to tease those stories out for a curious reader, then you’ll be onto a winner. In Poet Mystic Widow Wife, having four very strong female characters who were writers, who I could directly quote from, meant that I always had a hook for the historical material, a way to breathe more life into the facts and background.

5. Could you talk us through the publication process? Did you have to find a literary agent? And if so, did you have to have the entire book written beforehand?

I got a call from my agent in lockdown – I remember being so excited. He’d heard me on the radio talking about Margery Kempe and wondered if I had any ideas for a trade book. I’d wanted to write something more accessible for a number of years but had no idea how to go about it. We threw some ideas around but none of them stuck, and he advised me to spend some time writing smaller form pieces for publications like BBC History Extra to see how they landed with readers. I was a little deflated – I’d let my ego get the better of me thought the call was to say “can I represent you?” – but on reflection I’m glad I took some more time to test out ideas. I took his advice, and doing so helped me fine tune my pitch and crystallise what stories I really wanted to tell, as well as get a better sense of how publications responded to different areas of my research. A year later I got back in touch and, thankfully, he felt we now had something we could sell. We worked on the proposal together – it took about four months to put together and included a chapter outline, an introduction, a sample chapter, and examples of other similar books, as well as a brief bio for myself. He then took the proposal to auction, and I was lucky enough to get a contract with Bloomsbury.

6. What was your experience of the editing process?

I’ve been blessed with incredible editors. The first of these was my agent who helped me completely transform my sample chapter and introduction for the book proposal – without his insightful suggestions, I’m not sure the book would ever have sold. I then worked with a number of different editors at Bloomsbury at different stages. This process, for me, felt supportive and collaborative from start to finish. I’m familiar with the academic world, where peer reviews of articles can often feel like a vehicle for meanness, a chance for someone to exorcise their bad day. I remember one of the first reviews of an article I ever received saying that my writing was “fundamentally unscholarly” – I’m still not over that one.

The editing from my agent and the team at Bloomsbury, however, was consistently kind. That’s not to say it wasn’t sometimes ruthless – there was plenty of killing my darlings and rousing myself for another round of edits when, really, I didn’t want to look at the manuscript ever again…! But, because we were always on the same page in terms of a vision for the book, this never felt critical. It was always “what’s best for the book”, “how can it be the best it can be”, not “you’ve done this wrong, you idiot.”

In terms of what I found surprising (based on my experience with academic publishing) – the editing was more thorough and hands-on than I’d been used to and there was a lot more copyediting than I’d previously experienced. For me, this was a real plus, as I’d never written a trade book before and I’d written so much of it when sleep deprived…! So I was very grateful for such careful eyes.

7. What would you like for readers to take away from this book?

I have always been utterly fascinated by the words and lives of the four women this book follows and I’m excited to share their stories with a wider readership – honestly, it’s a privilege to be able to do that. I hope readers finish the book with more understanding of what it was like to be a woman in the Middle Ages – how hard women’s lives were, and how difficult it could be navigating a largely patriarchal society – but also more understanding of all the incredible things women were doing at the time. We often think that women weren’t able to have much impact on the world in the medieval period – that they were uneducated, couldn’t have a job, had to do everything their husband told them, were never in positions of leadership. But all four women, in different ways, show that women found a way to influence their society, even when the odds were stacked against them. I find their lives inspiring and I hope that readers will, too!

Dr Hetta Howes is a Lecturer in Medieval and Early Modern Literature at City, University of London, and a BBC/AHRC New Generation Thinker. She regularly contributes to broadcasts on BBC Radio 3 and 4, as well as writing for publications such as The Times Literary Supplement and BBC History Extra. She has a BA and MPhil from Cambridge University and a PhD from Queen Mary, University of London. Howes has published on the tropes of crying and cleansing in medieval Passion meditation, on blood and shame in medieval lyrics, and on the role of sight in fourteenth-century alliterative verse. Her academic book Transformative Waters in Late Medieval Literature was published by Boydell and Brewer in 2021. Poet, Mystic, Widow, Wife is her first book for a popular audience.

Comments