Author Ian Stephen looks at the process of bringing real-life adventures to the page...

Since about 2002, I've been sailing through stories. On purpose. Mostly. My proposal, which has now become a book, begun with the simple idea of navigating my own vessel through the sea-routes suggested by some of the timeless maritime stories set in Scotland's West Coast. Most of my previously published work, in book form, takes the form of poetry and short-fiction and I've published one long novel which is really two books in one. Thus, I am writing this from the perspective of an author who has only recently found a way to mould the personal experience of coastal sailing adventures into a work now published by Adlard Coles Nautical. As I used to write a regular hillwalking column and once contributed a chapter on island ridge-walking to Classic Walks (Diadem Books) I'd suggest, from this, that the experience of writing about sailing can be applied to writing about other adventurous pursuits.

Detail at the time

For me, it is essential to take notes, in some form, while the experience has the senses tingling. This does not have to be close to a finished form but timely documentation has two advantages. Accuracy is essential. It will make the story all the stronger. It is difficult to achieve, in retrospect. If you are with companions there is often a fascinating discrepancy between each person's memory of the event but that can cause confusion. A log-book or diary will often correct misleading memories. But it can also suggest the bare bones of a narrative. I often find that the words used at the time catch the spray and the colour that bring the journey alive for a reader. But then it sometimes needs time for comparisons and craft to place each journey in a context.

The technical stuff

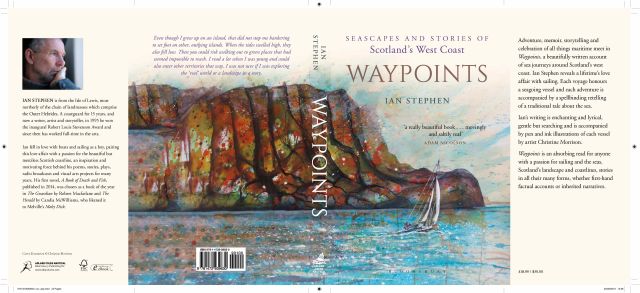

Again, I'm going to act on the premise that the issues in writing about sailing adventures for a general audience but also one which includes very experienced sailors, are similar to those in writing about climbing, ski-ing or surfing. If your audience is your peers in the activity or sport, this issue does not really occur. The appropriate language can include specialist terms as a type of shorthand. If you consider the story of your adventure may have appeal beyond those who also kayak or perhaps climb on ice, technical terms can be a problem. This was exactly the issue I faced in shaping Waypoints. One premise is that the structure of vessels has a lot in common with the structure of stories. To explore this, accurate descriptions of different types of boat construction were necessary. When it came to accounts of the passages and pilotage, there are particular navigational terms. If I spelled these out, every instance, I would risk alienating experienced sailors. If I 'spoke' only to fellow-sailors I would not be sharing the passion which prompted the book with people who were not 'in the know'.

I would say that this was where an objective eye and ear is good. I tested sections on readers ranging from a master-mariner to a North American friend who loves both literature and Country music but has done no sailing. My agent's comments were also useful. When it came to a contract, the commissioning editor pointed out an instance here and there where a short explanation would help. Drawings by my collaborator, Christine Morisson, who illustrated the book, often saved wordy expansions. Maps and chart-sections helped orientate the reader.

Most of all, I would say, the advice to write the book you really want was the most crucial. No matter how strong the idea is, it seems to me that its successful realisation can only happen in the writing. There were countless drafts, most of them read out loud, to myself or to my partner in art and life.

The underlying essay

I don't think the re-drafting was a matter of polishing the form. For me it was as much about shaping an underlying essay, developed from the working concept. Perhaps the act of writing is not so different from becoming fluent in climbing moves or getting 'in the groove' of sailing to windward. There's a wonderful feeling of satisfaction when you sense it's all going sweetly. For me, in the physical activity or in the writing, you hope to reach a stage where it just seems elegant. This might be as much about words left out or losing unnecessary movements. We all put-off the writing, convincing ourselves that we have to think it out a bit more first. For me, now, much of the thinking-through of the underlying essay happens only in the partly playful act of recreating the adventure, with language. In fact, this has become a new adventure.

One last point

My own first drafts played things down too much. This is what we do when we talk to our mates. Now I try to step outside myself and imagine how these waves must look to someone seeing them for the first time.

Ian Stephen is the author of the novel, A Book of Death and Fish (Saraband) – a book of the year in The Guardian, The Herald and Glasgow Review of Books and Waypoints, seascapes and stories of Scotland's West Coast, Bloomsbury 2017.

Comments