Elise Valmorbida explores the difficulties of avoiding clichés when writing about love.

I love asking my creative writing students to write about love. Falling in, being in, falling out of. Why? Because love is so vital, so exciting, so immense. Because love has been written about endlessly. And so love lends itself to cliché.

Clichés are works of genius. They are great and true and everlasting. The first few times a cliché-to-be is uttered, the listener must be amazed at the precision of it, the fresh and potent resonance. The earliest babbling brook made pictures and sounds: Nature possessed of a mind and a will, water talking.

Like every other up-and-coming cliché, the idea is so good it is quoted, repeated, and quoted, and repeated, again and again. And again and again and again and again and again and again and again and again and again and again and again and again and again and again and again and again—until we stop paying attention. Until we don’t really see it or hear it any more.

Every important emotional event is prone to cliché. That’s why it’s so hard to write sincerely about love. And lust, sex, birth, death, anger, fear, crying, fighting, remembering... Memories came flooding back. It seemed like only yesterday. The town was picture-postcard perfect. She loved him more than words could say, with every fibre of her being. They fought like cat and dog. His eyes glazed over. She clung onto him for dear life, but he was dead, dead, dead. It was the last twist of the knife.

Actually clichés are almost fun when they’re crowded together like this. It’s something of a costume party. Shakespeare relishes romantic clichés especially when he subverts them:

My mistress' eyes are nothing like the sun;

Coral is far more red than her lips' red;

If snow be white, why then her breasts are dun;

If hairs be wires, black wires grow on her head.

I have seen roses damasked, red and white,

But no such roses see I in her cheeks;

And in some perfumes is there more delight

Than in the breath that from my mistress reeks.

In Orwell’s essay ‘Politics and the English Language’, he writes about dying metaphors, those images and phrases that are worn-out and “have lost all evocative power”. The effects: ugliness, staleness, laziness, imprecision. Oh yes, and misuse. Too often, those poor dying metaphors are twisted out of their original meaning. The alternative? What about this, courtesy of Hemingway: “All you have to do is write one true sentence. Write the truest sentence that you know.”

Writing one true sentence about love is really hard.

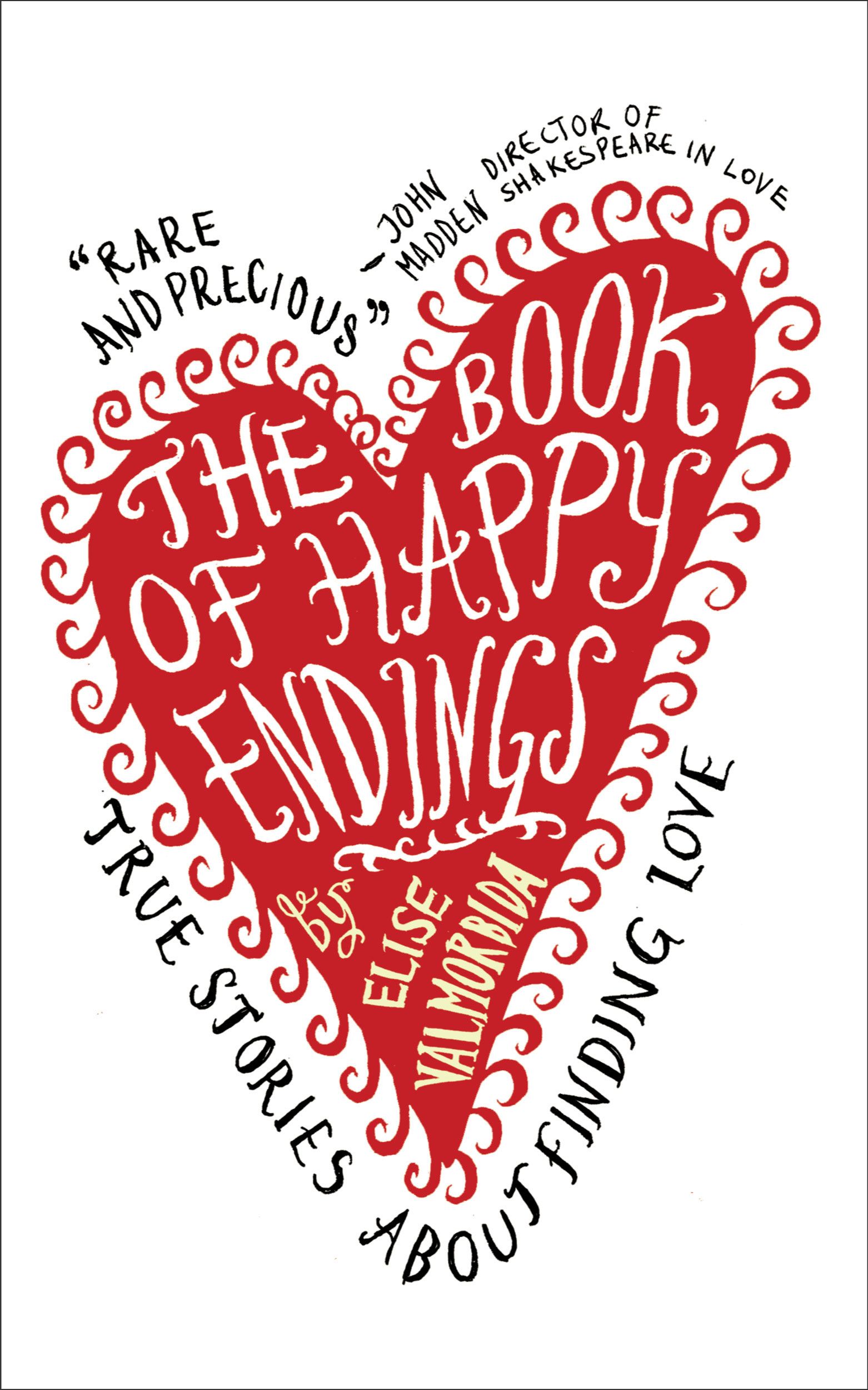

When I was starting work on The Book of Happy Endings, I was braced against the clichés. My own. And those of my interviewees. Clichés of language. Clichés of thought. But in my desire for emotional truth, I certainly didn’t want to plod or stumble into dull sincerity. The interviews lasted hours and hours. They continued later, in emails and phone calls. Once people knew they could trust me, and allowed themselves to remember an experience as if for the first time, they became spontaneous, and their sprawling stories were full of surprise and discovery.

Rosi: “You heard voices—but I saw light, this amazing light effect. I saw you surrounded by light, wearing flaming yellow clothes, a bright yellow top that shone like an angel, so blindingly light I practically had to wear sunglasses—”

Anneke: “I don’t even have a yellow top.”

Rosi: “Maybe I was winking at you because the light was so bright!”

Anneke: “I look awful in yellow.”

Sometimes the plainest words were the most emotive…

“I’m not greedy. I just want one person. The world is so big and there are so many people, but I only want one.”

Sometimes it was the most understated action…

Vilmos sat in the wedding car that collected Kati from the hairdresser’s. She was about to get married, but not to him.

“At the hairdresser’s, I said I’m going to a wedding, will you make my hair nice?” Kati told him later. “I never said it was my wedding.”

This same Kati didn’t marry Vilmos until she was in her eighties. They’d been together for many decades. Their decision to marry was prompted by the telling of their story in The Book of Happy Endings. I couldn’t have predicted it.

How many times have you heard a disappointed someone say: “And you just KNEW what was going to happen next”? This is not because the plot itself needed to be changed. Romeo and Juliet can still fall in love, be star-crossed and die. There’s life in them yet. A clichéd love story is one that needs to be told differently.

Tentative writers often ask if this or that story hasn’t all been done before. Of course it has. How many star-cross’d lovers stories are there? (Lots.)

But that didn’t put Shakespeare off. In fact he was inspired by it. He based his plot on The Tragical History of Romeus and Juliet, an English narrative poem—which was inspired by an earlier Italian story—which was inspired by tragic love stories from antiquity. Ovid’s tale of Pyramus and Thisbe (itself comically reworked in A Midsummer Night’s Dream) features rival families who get in the way of true love, and the layered misunderstandings that lead to each lover’s tragic suicide.

This weighty recycled heritage didn’t put off the creators of West Side Story. Nor did it deter the writing of more than twenty Romeo-and-Juliet-inspired operas. The Indigo Girls sing the romance again, memorably new. Film-makers have not been shy, either.

But how far to go with re-invention?

There’s an annual event all love-writers should know about: the Literary Review’s Bad Sex in Fiction Award. This prize is bestowed on “the most egregious passage of sexual description in a work of fiction”. We’re not talking here about pulp fiction or tactical erotica. The nominees are distinguished literary writers.

So what happens? They try too hard. The metaphors strain until they split. Elaborate language masks a lack of emotional courage. Sometimes, in an act of bad faith, a wild contrivance is thrown in. (Weird words, a random animal…) Or too much mechanical detail creates an emotion-free zone. Sometimes I get the queasy feeling that a writer is super-imposing his own iffy desires onto his unsuspecting character. It’s the wrong kind of creative vulnerability.

Writing about love, about making love, and unmaking love, is not easy, because authenticity is not easy. Authenticity might not even be interesting! But it’s sure to be more interesting than lazy thought or poorly understood feeling.

PS: Three writers who write gorgeously about love

Jane Austen: she does, she really does—make time to read her again

William Shakespeare: for seduction and subversion by sonnet, for dramatis personae who kill and die and live for love, for lovers who are in love with the language of love

‘Socrates’, via Plato: “Love consists in being conscious of a need for a good that is not yet possessed.” — What a great prompt for your love story.

Elise Valmorbida’s works include Matilde Waltzing, The TV President, The Winding Stick and The Book of Happy Endings, published in four languages and four continents. She is the script consultant and producer of award-winning Britfilm SAXON, for which she was honoured as Trailblazer by the Edinburgh International Film Festival. Elise teaches Creative Writing at Central Saint Martin’s and Arvon. She is on the Board of writers' organisation 26 and is External Examiner for Falmouth University’s MA in Professional Writing. Elise is currently working on a creative writing guide and an Italian-Australian historical novel. Find her on Facebook here

Comments