As part of his series of articles for writersandartists.co.uk on his new Howdunnnit Machine, author Malcolm Pryce now considers a question no one asks. What is reading?

After sex and shopping, it is probably Mankind’s most popular recreational activity. Yet few people ever bother to inquire about this daily miracle. What actually is reading anyway? An understanding of its mystery can be enormously helpful. Not in any abstruse theoretical sense, but in the directly practical one of clarifying what our task is and thus make us better at it.

In essence, when we read we enter an altered state, like a trance. Psychologists call it narrative transport, some people call it the fictive dream. Ordinary folk call it being absorbed in a book. Just as Alice passes through the looking glass into Wonderland, so to when our eyes come to rest on those strange black squiggles called words we pass through them into a different realm. Where are we? We are in a dream, the script for which is provided by the words. They are the stage directions, or if we think of a movie script, they specify location, camera angles, action sequences and, of course, the best bit: dialogue. As Elmore Leonard said, people don’t skip dialogue.

Don’t ask me how exactly the ore of meaning is unpacked from the black squiggles. I can only tell you it takes place somewhere in that region of the brain known as Wernicke’s Area, next to the Superior Temporal Gyrus. Which is about as helpful as saying Jesus turned water into wine in the kitchen rather than the lounge.

It doesn’t matter. The important thing is this: reading fiction is a form of enchantment, self-enchantment, and people find it deeply pleasurable, often far preferable to the disenchanting world they otherwise inhabit. At the heart of the pleasurable experience lies a subtle paradox. To understand what it is, cast your mind back to your childhood when you played hide-and-seek. Remember the terror that gripped you when you thought you were about to be caught? Your heart pounded, adrenaline surged through your veins, you might even have screamed. Why? In truth, you weren’t in any danger at all, were you? That bloke pretending to be a ferocious giant chasing you was your dad. So why did your heart pound in fear? Why do people at the movie cry genuine tears? Why would someone pay money to be upset for two hours? The reason is this: you can enjoy the powerful visceral emotional experience in safety. It’s like a walled garden of the heart. Inside it you can experience all manner of terrible or beautiful things, whilst outside it, cerebrally perhaps, you know you are safe. You can round Cape Horn without getting wet. You can spend some time, strangely fascinated, in the company of a violent delinquent thug like Alex from Anthony Burgess’ A Clockwork Orange. You can even get some strange pleasure from the company of Humbert Humbert, the narrator of Lolita, someone who would normally make our skin crawl and inspire us to phone the police. It’s like a rollercoaster. You scream on a rollercoaster because your ancient limbic fear system says you are plunging to your death. At the same time you know it is just a ride.

This visceral emotional experience is what readers crave.

They are junkies for it. Roddy Doyle got into a lot of trouble a few years ago when he voiced the heresy that he couldn’t be arsed to read James Joyce’s Ulysses. What? Not read the greatest novel of the 20th century? Burn that heretic! In truth, I suspect he was just articulating something that most people thought, but few dared admit. Reading Joyce is the literary equivalent of eating your greens. 95% of readers are not looking for it, they are looking for a book that swallows them up such that they can not put it down. Literary agents who nowadays act as guardians at the portals of Publishing Narnia are keenly aware of this.

Our task then is first to inveigle readers over the threshold, into the Garden, using a breadcrumb trail of words. As we shall see, not just any old breadcrumbs will do. Once there, the trick is to find ways to keep them there. We use language in specific ways to make the dream so beguiling they don’t want to quit. And, most importantly, we tap into their brain's pleasure reward system in a manner divined a thousand years ago by the great medieval neuroscientist, Scheherazade. It’s called storytelling and involves hooking our readers on the neurotransmitter dopamine. In the next post I will examine how this works. I hope you will join me and learn the dark arts of peddling dopamine.

Read the first article in this series here

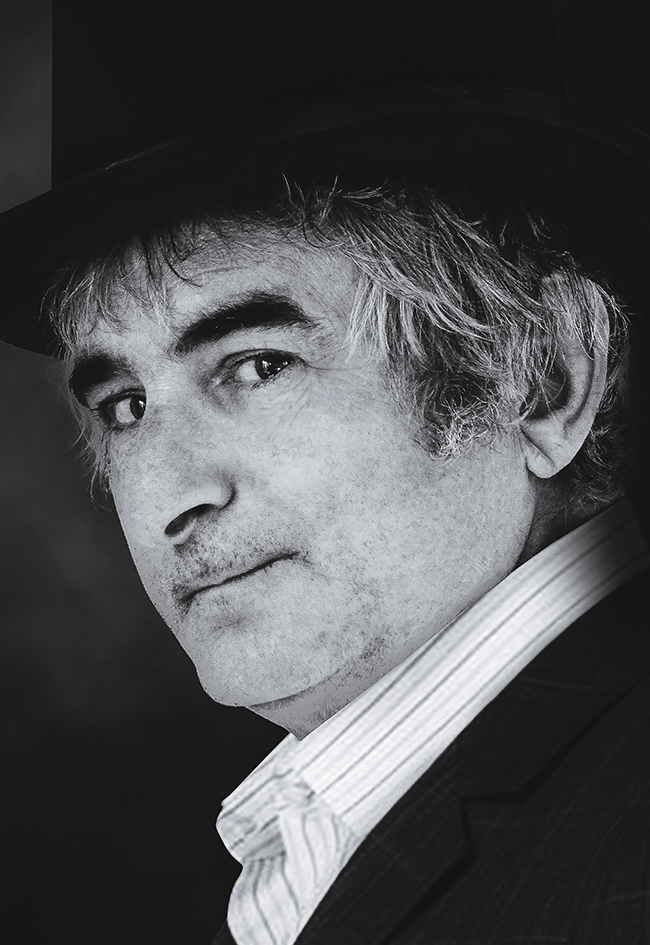

Malcolm Pryce was born in the UK and has spent much of his life working and travelling abroad. He has been, at various times, a BMW assembly-line worker, a hotel washer-up, a deck hand on a yacht sailing the South Seas, an advertising copywriter and the world's worst aluminium salesman. In 1998 he gave up his day job and booked a passage on a banana boat bound for South America in order to write Aberystwyth Mon Amour. He spent the next seven years living in Bangkok, where he wrote three more novels in the series, Last Tango in Aberystwyth, The Unbearable Lightness of Being in Aberystwyth and Don't Cry for Me Aberystwyth. In 2007 he moved back to the UK and now lives in Oxford, where he wrote From Aberystwyth with Love, The Day Aberystwyth Stood Still, and, most recently, The Case of the Hail Mary Celeste.

Visit Malcolm's website here or get to know him a bit more by following him on Twitter.

Comments