Setting is an anchor. It has the ability to weight a story in any given time, or place. Daphne Du Maurier saw setting (her beloved Cornwall) as another character, intrinsic to plot. And, if you take Du Maurier at her word, that means that for every well-developed protagonist, antagonist or minor character, there is an omnipresent ‘super-character’ binding them together. That character is setting. For me, nowhere is this more relevant than in historical fiction, where entire worlds need reconstructing in believable detail.

Is your setting alive or just background?

Setting is an anchor. It has the ability to weight a story in any given time, or place. Daphne Du Maurier saw setting (her beloved Cornwall) as another character, intrinsic to plot. And, if you take Du Maurier at her word, that means that for every well-developed protagonist, antagonist or minor character, there is an omnipresent ‘super-character’ binding them together. That character is setting. For me, nowhere is this more relevant than in historical fiction, where entire worlds need reconstructing in believable detail.

Du Maurier’s Cornwall is full of literary swagger, whether using the backdrop of the English Civil War (The King’s General) or an 18th century inn on a desolate moor (Jamaica Inn). Once a reader is exposed to a well-crafted setting, it becomes difficult to mark the boundaries between what is fictional and real. Any reader of Jamaica Inn visiting the Cornish coast will be hard pressed not to see her wreckings and drowned men. Likewise, I cannot think of the frost on an Amsterdam canal without imagining Nella Oortman slipping between them in Jessie Burton's The Miniaturist and I can literally hear Sarah Water's Blitz-ravaged London from The Night Watch groan with life inside the pages of her book.

As a writer, you will have your own ideas about how to create believable settings when writing outside of the contemporary. Here are five of mine. These are observations that have stuck with me and which certainly strengthen my own ability to write into the past with what I hope is at the very least, a stroke of authenticity.

1. Know what they know

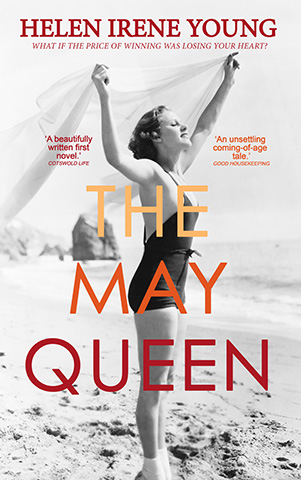

Draw a map if it helps. When I created the world of The May Queen I did just this. To recreate 1930s Fairford, I sketched out a skeleton view of the small Cotswold town and drew in every street, lane, and road in and out. On to this, I used contemporary accounts to plot each shop, business and residence that I knew existed at the time. It really informed my sense of distance between locations and the sense of small town life my main character, May, would have experienced. For May, there is always someone watching, I knew I wanted this implied, but I hadn't quite realised how true it was, until I could see it, as she would have.

2. Dress your scene

I studied theatre at university and so always think of fictional settings in terms of how I might dress a stage set. You must develop the ability to stand back and throw out anything that threatens your period world. In one scene in my own work, I had a radio perched on the mantlepiece above a fireplace but when I sought out advice from an expert on early radios, he said it most definitely would have had an accumulator battery, meaning it would have been too heavy to go where I’d originally placed it. Such a small detail but one which was vitally important. I’d already marked the town electrical supply store on my map and so it gave new meaning to that place too. I better understood how reliant people were on the store itself and this gave me something new to play with.

3. Go beyond the boundaries of your narrative

Depending on your period, there will be some form of media, news or gossip at play that informs the day-to-day lives of your characters. If this happens ‘off-stage’ be clear with yourself. If it isn't intrinsic to the plot, simply knowing about it is enough, you aren't there to give an historic account of the period.

The world outside of the narrative is vitally important, but only borrow what you need and no more. In The May Queen, my character wants her hair cut into a fashionable bob she has seen in a magazine. By the 1930s, this hairstyle was falling out of fashion, but May doesn't know this. Her view of the world is outdated. It has taken a while for this style to catch on in her little town. I’m not sure I even allude to this in the novel, but it is implied and there are many subtle threads like this one running throughout. I think there is strength in subtlety. It implies confidence in what you are writing about. You can only hope that your reader will agree.

4. How nature can help

I have a love of the outdoors which informs how my characters behave. I can’t help myself. Like my own heroes, Hardy and Du Maurier, I want to get under the skin of my countryside setting so that it is as loved by the reader as it is by my characters. I learnt a lot about birds for one, researching those that lived in the Cotswolds at this time, beside rivers (coots and little grebes), or in trees (nuthatches) as well as those commonly seen in the village (spotted flycatchers and house martins). Ones common then, but not all necessarily now. In my next novel, set in Colombia, I’ve got a condor (!). Changes to place are more subtle in the countryside than if you’re recreating a city setting because time moves more slowly here, and so I found birds, flowers, even farm implements, a good way to achieve period accuracy.

5. Show differing views

You may have two different characters who see things in completely different ways. Perhaps they have different experiences, educations or are of a different age. Opposing forces in fiction are a great tool for shaping your reader’s understanding of place. In my own writing, I love being able to suggest different ways of seeing the same thing. For example, one of my main characters, Christopher, climbs a tree because he wants to show his strength. May, watching on, is in awe of the way he manipulates this everyday structure. Her view of it is changed because of how he approaches it. For May, it will never be the same tree again. Associating place with character, abandons something of that person to it too. In this instance, I was able to show Christopher’s cruel indifference to nature. His world is one of parties and long weekends. He is a visitor, from another world within this one, whilst it is all May knows.

Helen Irene Young is the author of The May Queen (published by Crooked Cat) and a digital editor. She attended the Faber Novel Writing course and splits her time between London, Wiltshire and Colombia, when she can get there. The May Queen is her first novel. Follow Helen on Twitter here.

Comments