Four years ago I wrote about where I get permission to take risks in my short stories. Since then, much has changed.

This year sees the publication not just of my third short story collection, but also my first poetry collection. POETRY. When we last met, I was not a poet. Don’t tell anyone, but I didn't like poetry. I didn't understand it, I liked my words to stretch from one margin to the other. Line breaks? Why would anyone want to do that? How do you read them? What is a line? Where are my sentences?

So, how did I get from that to complete adoration of the line break, an insatiable appetite for reading poetry, and even to calling myself a poet?

Very slowly. And with many shots of permission along the way.

Permission to write poetry came differently from short story permission. I had always been writing prose (I never called it “prose” until I started hanging out with poets, for goodness’ sake!). I read stories as a child, so I knew roughly what one should look like on the page. After a few years, though, I needed permission to take myself seriously as a writer – and then the largest permission injection to propel me to my next stage: taking risks in my writing, experimenting.

With poetry, I needed permission to even begin. The word “poet” seemed forged of the heaviest metal, that no ordinary mortal could lift, to which were attached centuries of history, chests full of vocabularies and unfathomable terms. Iamb! Sestina! Shakespeare! Milton! Betjeman! (All men, yup.)

It started for me – as so many of my adventures have – on a ‘Writing Radio Drama’ Arvon course taught by BBC radio producer Sue Roberts and her rather famous poet husband Simon Armitage. I really did want to learn about radio drama. But I also wanted to sidle up to Simon with a handful of my flash fictions and say: Do you think I might also, perhaps, maybe be writing poetry?

Well, I did. And he said: Yes, you might definitely be writing poetry. He pointed me towards James Tate, the Pullitzer Prize-winning American poet, whose poems look like… flash fictions! Oh my, I thought. If these are poems, then maybe I could … ? Step 1 completed.

Step 2 involved The Line Break. I did what I always do when I want to learn something: I went on a workshop. (Actually three, all taught by the very patient and excellent poet Pascale Petit). These workshops were not just on writing, but also on reading poetry, and I cannot stress this strongly enough: reading closely and thoughtfully teaches you everything you need to know. You don’t have to go on workshops, although they can be invaluable, introducing you to fellow writers. But I don’t believe anyone can write well if they don’t read.

I want to apologise to the workshop tutors and participants for my incessant shouting of “What is a line break? I don’t get it! I don’t get it!” But then Pascale gave us a poem without its line breaks and asked us to put some in – and suddenly it clicked. I felt it. Step 2 completed.

But poems aren't prose-with-line-breaks. For me, the writing process is entirely different – with prose I have to have my fingers moving, but poems come to me out loud, more like a song, a physical, vocal process. And whereas my fiction is very fictional, my poems are often autobiographical; the shape of a poem gives me permission, it appears, to document more directly what happens in my life.

When a poem was commended in the 2014 Magma magazine short poem competition, I read at the prize event – and, for the first time, I felt welcomed by the poetry community. No-one interrogated me on the rules of sonnet-writing or what rhyme and meter are. Everyone was lovely. A week later, I bought a new notebook in a fit of excitement after hearing three fantastic poets read – Jo Bell, Helen Mort and Alan Buckley – and suddenly the poems came pouring out. Practically one a day. These shots of permission unlocked the floodgates.

What I found I urgently needed next was for People Who Know to declare that what I was writing were Poems. I was already in the habit from 10 years of writing short stories of submitting work and I did the same now. Slowly, slowly, a few poems were accepted. But I still didn't believe I was a poet. Then my chapbook of what-I-hoped-were-poems won second prize in a poetry chapbook competition. The chapbook was published in February 2016, and I really thought that reviewers would say, Nonsense, these aren’t poems, they’re short stories, she’s a short story writer, pshaw.

It didn’t happen.

I nearly fell over a few months later when Nine Arches Press said they'd like to publish a full poetry collection. I still wasn't calling myself A Poet. I was still saying when I did readings that I didn't "get" the line break.

Where am I now? Well, I introduce myself to people as a poet and short story writer. I've stopped talking about my fear of line breaks because I've fallen in love with them. I love the ambiguity they can add, the way they squeeze more out of words at the end of one line and the beginning of the next, how they work with the breath, can make a reader read faster or slower, how the form can reflect the subject I am trying to write about.

What I need permission to do now is to get to the place I had already reached with short stories, a place of complete lack of inhibition, writing only to please me, declaring “This is a short story/poem because I say it is”. For this, I am reading, always reading, widely, deeply, across genres and languages, and it’s starting to happen.

My latest adventure, in the book I wrote for my PhD, is in hybrid writing: moving within one piece from poetry to prose, from fiction to non-fiction. This is all very new to me, and thrilling. Who knows what might come next? Stay tuned.

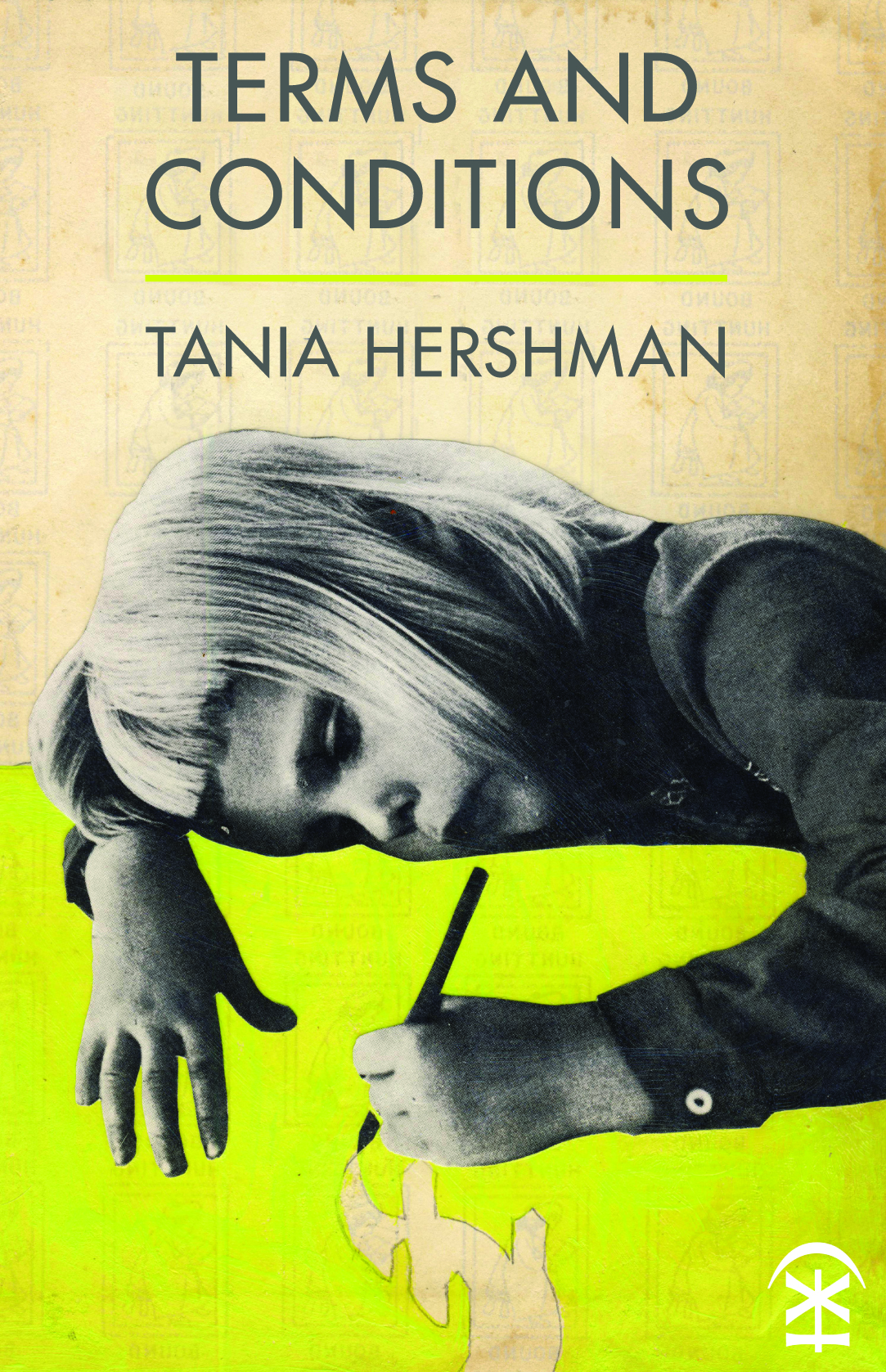

Tania Hershman’s debut poetry collection, Terms and Conditions is published on July 14th by Nine Arches Press and is now available for pre-order, and her third short story collection, Some Of Us Glow More Than Others, was published in May by Unthank Books. Tania is the author of two further short story collections, My Mother Was An Upright Piano (Tangent, 2012) and The White Road and Other Stories (Salt, 2008), and a poetry chapbook, Nothing Here Is Wild, Everything Is Open (Southword, 2016), co-author of Writing Short Stories: A Writers' & Artists' Companion (Bloomsbury, 2014), and curator of ShortStops (www.shortstops.info), celebrating short story activity across the UK & Ireland, and is completing a PhD in creative writing and particle physics. www.taniahershman.com

Comments