Article

4 min read

Edited

13th October 2020

- Read short stories. As someone who tried to write a novel while reading only story collections, I urge you to read whatever form you are working in. (I am presently in the process of re-writing that novel from scratch.) Short stories run off a different momentum and pacing than novels. A single moment can release the story like a Roman candle, and when that momentum fades, the story ends. Of course some stories release their energy more like porridge oats than a Roman candle, but generally novels take the most time to unfold. If that slow unfolding is all you are reading at the moment, there is a good chance your story will be baggy. Stick to writing novels if they are the only form you are reading.

- Read poems. Every story author can learn from the economy, elision, and play of language you find in good poetry.

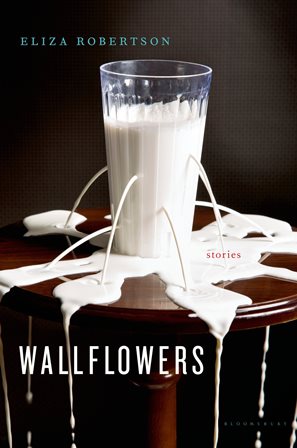

- Read the newspaper / browse news websites for inspiration. Short stories are the ideal medium to explore to explore those truth-is-stranger-than-fiction stories you might not sustain for an entire novel. Example: a few years ago, I stumbled across the CBC headline, "Missing Tiger, Camels Found Alive." That headline is now the title of a story in Wallflowers that dramatises the zoo animal theft that warranted the news slot in the first place.

- Experiment with form. We feel blocked not simply because we do not know what to write, butalso because we are not sure what form to express the story in. Sometimes a straight-forward narrative style is the cleanest, most effective option, but not always. Writing a story as an epistolary or horoscope may get you out of a rut or release new ideas—you never know.

- Ask yourself surprising questions about your character. Not simply, "what did Fatima eat for breakfast," (how much emotional resonance can you find in a bowl of cornflakes anyhow) but - "when was the last time someone saw Fatima naked?" or, "when was the last time Fatima cried?" or, "when did she last say, 'I love you.'" These details may not appear in the story itself, but they will lend your character what Adrienne Rich words as, "the sheer heft of our living." This heft deepens the scenes you include on the page and projects the shadows of your character's past and future.

- Imitate. Write a simple scene of your own. Maybe it's from a story you have already written, or a memory of your parents feeding you Welsh rarebit, or a scene you observed at a bus stop. Rewrite the same scene into the styles of three authors you admire... For example, William Faulkner or Angela Carter or George Saunders. What new details do you observe? How does your language / syntax / pacing shift between each style?

- Try a new point of view. If you always write in the first person, try the third or second. My friend Dave insists the second person point of view helps him win contests. I don’t know if that’s true, but it’s worth a shot.

Eliza Robertson was born in Vancouver, Canada in 1987 and grew up on Vancouver Island. She studied creative writing and political science at the University of Victoria and then pursued her MA in prose fiction at the University of East Anglia. While there, she received the Man Booker Scholarship and the Curtis Brown Prize for best writer. Robertson is now a highly celebrated short story writer; in 2013, she won the Commonwealth Short Story Prize and was a finalist for the Journey and CBC Short Story prizes. She currently lives in Norwich and is working on completing her first novel. Find her on Twitter here and find out more about Wallflowers here.

Writing stage

Areas of interest

Comments