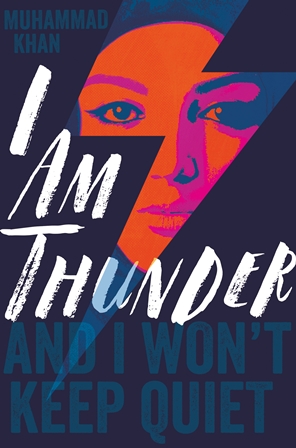

I Am Thunder is my debut novel. Want to know a secret? It was written by a maths teacher who was trying to find his writing voice, while writing about a teenage protagonist who was trying to find hers.

There are definite shades of the blind leading the blind here, but in reality this paradox was the beginning of a beautiful working relationship. My protagonist and I were about to embark on a literary journey of discovery together – the ultimate team-building exercise. We got to know each other, tested our limits (I threw tribulations and heartbreak at Muzna, she robbed me of my social life and sleep – a fair trade) and eventually learned to trust one another.

I now know a hundred and one details about Muzna that never made it into the book. Too much information? Perhaps, but I like to think these details subconsciously informed the broad strokes of the narrative and helped me to find my writer’s voice. Besides, Muzna and I are better people for it. She became a living, breathing heroine who knew exactly what she wanted and I became a published author.

How many times do we create interesting characters only to compromise them for the sake of the plot? In my opinion, too many. But if we allow ourselves to be guided, our protagonist is always ready to whisper the truth in our ear. In time, as the bond strengthens, you learn to look at things from a different point of view. Your main character may even start to thank you for the obstacles you place in their path, finally understanding that growth can only come from a struggle.

I have long been fascinated by the way students communicate with one another. As a teacher, it was my job to explain mathematical concepts to my students until they understood. Often this worked (go me!), but occasionally I failed (boo! hiss!). My next strategy would be to ask another student to have a go at explaining. They would repeat exactly what I had just said, sometimes with poorer grammar, interesting hand gestures and a raised eyebrow or two. Then – hey presto! – the first student would understand.

Herein lies a general lesson that can be applied to writing. People communicate through language, facial expressions and hand gestures. A writer must convey all three through voice alone. And voice means communicating authentically, which is not necessarily the same thing as correctly. So sometimes you need to sacrifice your literary gems – those nirvanic expressions and perfect phrases that make you sigh with literary happiness. Their sudden appearance interrupts your voice and can shatter the spell your writing has begun to cast.

Know that voice in your head? No, that’s Satan. I mean the other one. The one who knows your darkest secrets but loves you just the same. That is your writer’s voice. It is the antithesis of cold, factual academic writing. It flows with personality. The word choices you make and how you string them together will be as unique as a strand of your own DNA. Readers want a writer’s voice that they can trust, so sincerity and authenticity are the only things to keep them with you to the end. That voice is informed by your unique point of view: the sum total of your observations, love, pain, victories and failures. In short, it is the spirit left free to express itself however it damn well chooses.

Writing in more than one genre can be a great exercise to help iron out those pesky literary creases too. I wrote a fantasy novel which an agent said was just ‘too bonkers’. I then tried my hand at contemporary and got a better reaction. In this way I managed to chisel away at the extraneous techniques that were masking my true writer’s voice.

There is a scene in I Am Thunder where Arif (hot bad boy) asks to see one of Muzna’s stories. By this point, Muzna’s infatuation has progressed to love. But still she hesitates. It’s a key moment. Muzna knows her writing is littered with unspoken secrets and is afraid of revealing these to Arif for fear of rejection. Arguably this is the most intimate scene in the entire book. I wrote it because it made me feel horribly uncomfortable, but honesty is something readers appreciate. After some soul-searching, Muzna agrees to Arif’s request. The experience liberates her, giving her the power to eventually confront her nemesis – her writer’s voice.

The journey towards finding your writer’s voice can be frustrating, embarrassing and sometimes even a little humiliating. But once you’ve discovered it you will be liberated in ways you never thought possible. When you get there – and you will get there – sing loud and proud, and your readers will sing with you.

Muhammad Khan is an engineer, a secondary-school maths teacher, and now a YA author! He takes his inspiration from the children he teaches, as well as his own upbringing as a British-born Pakistani. He lives in South London and is studying for an MA in Creative Writing at St Mary's. He is working on his second novel for Macmillan Children's Books, Kick the Moon. You can follow Muhammad on Twitter here.

Comments