Historical fiction author Caroline Lawrence discusses why chapter outlines should be an integral part of a writer's storytelling process.

I write historical fiction for kids with an aim to educating them about the ancient world. Because there are so many facts and historical details in my books, they must have a strong plot to keep kids reading. Plot is the train that carries them through the world I want to show them.

Because plot is so important to me, I'm a fan of story structure templates, especially ones used by screenwriters from Hollywood. My favourite is John Truby’s story structure audio course but I also love Save the Cat and The Hero’s Journey.

I generally map out my book using elements of all three of these screenwriting structures. Here are some of the main beats I like to use: Hero’s World, Stasis = Death, Problem, Desire, Call to Adventure, Refusal of the Call, Mentor, Talisman, Threshold, Threshold Guardian, Opponent(s), Tests and Training, Collection of Allies, Plan, Minor Battle, Apparent Defeat, New Direction, Major Battle, Revelation, New Level.

Once I have jotted down the main beats of the plot, I write a chapter outline, where I note the main action of each chapter in one or two sentences. It sounds clinical, I know. But it is just a road map to keep me heading in the right direction so that once I go into intuitive mode I won’t wander all over the place. I try to get the whole book onto one or at most two pages.

When I have written the first draft, I usually go back over the chapter outline, which might have changed substantially from the original version. As I said, the structure is just a guide to keep me on track. Looking at the chapter outline at any stage gives me an overview of the shape of the book. Sometimes the author needs to get out of the trees to have a look at the general shape of the forest.

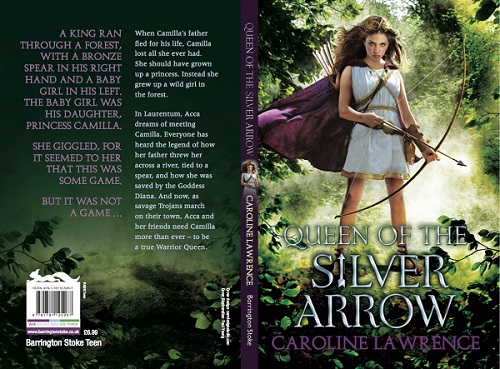

In my most recent publication, Queen of the Silver Arrow, a retelling of a story from Virgil’s Aeneid for reluctant or dyslexic teen readers, the outline showed me that although Camilla is the hero, the story does not work if told from her point of view. So I decided to make her friend Acca the protagonist and narrator, even though Virgil only mentions her twice.

One way of seeing if the structure is working is to summarize each chapter on an index card. At the top of the card is the chapter heading, which reminds me what the chapter is about. I put down a few key words to describe the action and the major elements.

That way I can see at a glance where I've repeated a beat or which chapter might be cut or consolidated. If the narration has multiple points of view, I jot down whose point of view this chapter is from. If I am really organized I’ll have a different colour index card for

each of the three POV characters.

Because it’s satisfying to have the main character of each scene end on a higher or lower level than where they started, I often do what Blake Snyder recommends and put a plus (+) or a minus (-) at the lower left and lower right hand corner of each index card. I also make a note of set-ups or pay-offs and any other features I want to emphasize, like scene deepening or recurrent images.

Last week I went to see my editor to talk about my rather choppy first draft of my work in progress, The Archers of Isca. I wanted to make sure the general shape was right before I started detailing the scenes. Before the meeting I emailed her a page with the chapter outline – title and a line describing the main action – but I also brought in the fifty index cards with a few key words for each chapter.

Looking through these together showed us that we could cut out the first seven chapters to get the action started sooner and keep the word count down. By putting the seven cards to one side, I can see at a glance which elements I’ll need to reinstate in my new opening.

Another factor that helped me stand back and see the whole shape of the book was talking about the story as I showed my editor the cards. She pointed out that although I mention Boudica and Druids, I never actually say why those two subjects are so scary and fascinating. Sometimes we mean to put things in but because we know them so well, we forget our readers don’t!

Throughout this part of the writing process, I remind myself of what the great director Howard Hawks once said: “A good movie should have three great scenes and no bad ones.” Writing all great scenes is something we can all aim for and just one more reason I make the chapter outline part of my storytelling process.

Caroline Lawrence is an Anglo-American author based in London. A graduate of UC Berkeley, Newnham College Cambridge and University College London, she is best known for her million selling series of historical novels for children, the Roman Mysteries. In 2007 and 2008, the BBC made a glossy children's TV series based on these books. In 2009, Caroline won the Classical Association Prize for "a significant contribution to the public understanding of Classics". Her books have been translated into more than 15 languages she has sold over a million copies. She has recently written two retellings of stories from Virgil’s Aeneid for dyslexic teen readers. Her latest project for middle grade, The Roman Quests, is about three children on the run in Roman Britain.

You can visit her website or follow her on Twitter here.

Comments