How do you write authentic and accessible dialogue for middle grade readers when your story is a piece of historical fiction?

Does writing dialogue come naturally to you? Or do you struggle to find an authentic voice for your characters?

Fear not, because dialogue really shouldn’t be as scary – or as difficult – as it sounds. After all, you’ve probably had a fair few conversations over the course of your time living on earth.

But if you’re writing a historical story for middle grade readers, how do you balance authenticity and accessibility? Why is it important to write dialogue that won't alienate readers today?

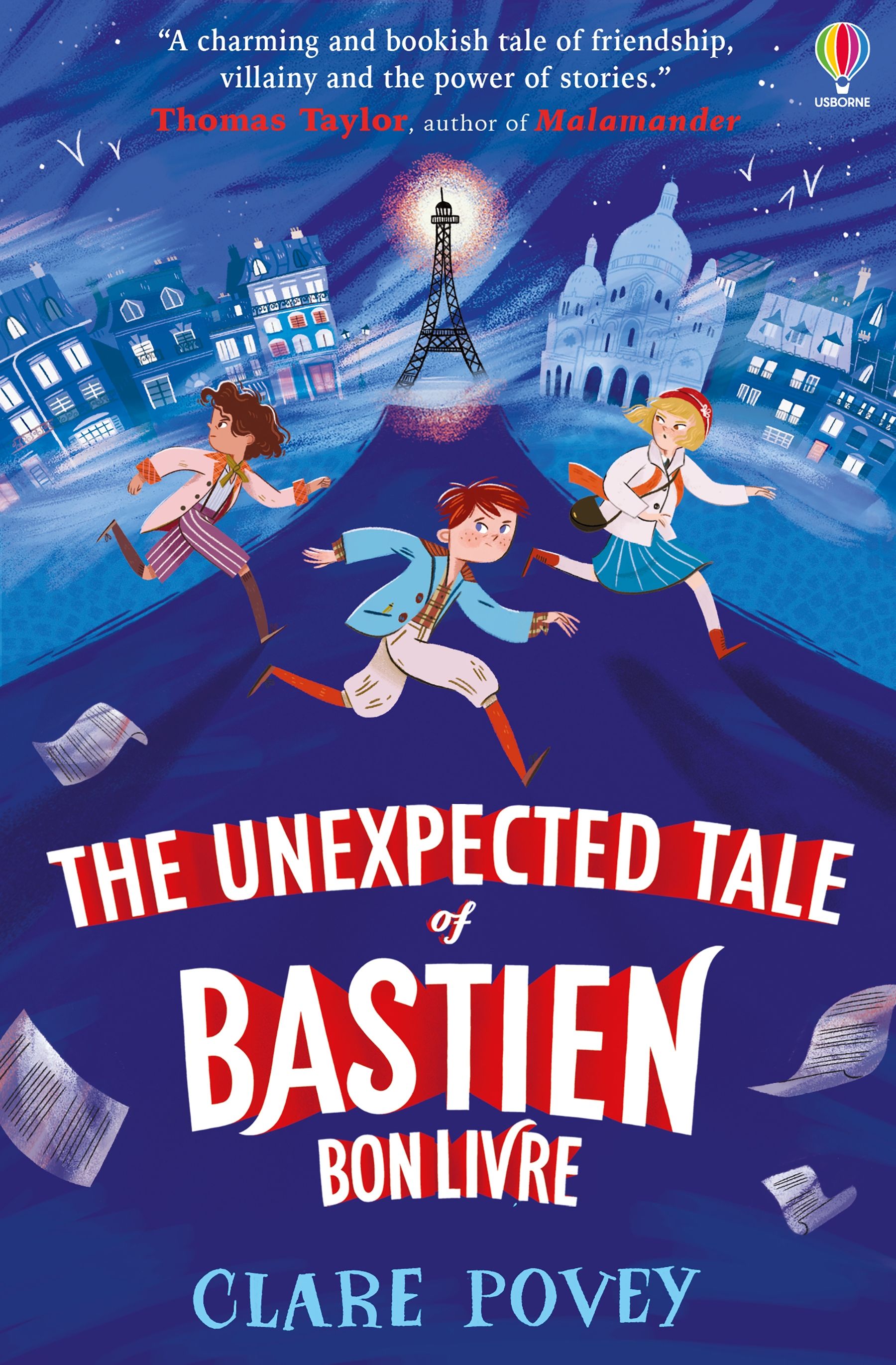

When I started writing The Unexpected Tale of Bastien Bonlivre, my debut middle grade mystery adventure set in 1920s Paris, I thought it was more important for me to authentically represent the time period in terms of characters and setting. I wanted to establish a strong sense of place and display Paris as an exciting city, full of cultural and social change. I therefore made the decision to focus all of my time and research to exploring the setting. For me, that didn’t include dialogue.

Why not? Well, I wanted to write conversations that would play out between kids today. Obviously, I knew not to drop a ‘so cool!’ or a ‘wicked awesome’ into the dialogue between my characters. The book is set in 1922 after all, but apart from that, I did give myself free reign to write what came naturally to me.

Although I wasn't born in the 1920s, children are always children. They moan about their family, lovingly tease their best mates, and chat in their own secret languages. They can be dramatic, but kind and caring. They aren’t afraid to say what’s on their mind or tell you how they feel.

Here are a few examples from Bastien, which hopefully gives you an insight into how I write dialogue.

TIP: If there’s one thing I could offer as a top tip it would be to use Merriam-Webster. If you search any word, they will tell you when the first known use of this word appeared so you can make sure that any language you include in your historical middle grade story is time appropriate.

Example One: Moaning

“Although sweeping did lead me to find plenty of this over by the fountain.” From Theo’s pocket he pulled a lump of a green moss. “I’m going to make earmuffs with it for everyone. I haven’t had a decent night’s sleep since I got here. Felix and Fred’s snorting is as loud as a foghorn!”

Bastien groaned in sympathy. “They even snore at the same frequency. I can’t take much more.”

Are your characters even real if they're not moaning about the bad habits of their friends? Where an adult might not vocalise their thoughts, children don't hold back so make sure this comes across in your dialogue.

Example Two: Teasing

“Will it work?” Bastien studied the bent metal wires of the lockpick. They didn’t look like the key to freedom.

“Have a little faith in me, would you? Your lack of belief is almost insulting.”

Me and my two best friends are guilty of teasing each other to no end. It's one of the many ways we show our love for each other and we have been like this our whole lives. I think this is a great way for your dialogue to feel fresh for your target audience.

Example Three: Secret Languages & Making Up Your Own Insults

“Last one to the river is a fromage-sniffer!” Bastien teased.

This was a phrase that survived the copy-editing stage! And I was very glad about that. Although fromage-sniffer might've not been an officially recognized phrase in the 1920s, both words still existed at this time. So why not mash them together? It shows the humour between Bastien and his best friend, Theo, and how they have their own words, a type of secret language.

Example Four: Exaggeration

“I think,” Theo mused, as they closed the bookshop door behind them and he bit into his pastry, “that I’m in love with this croissant.”

I am hugely inspired by my lovely, inquisitive nephew Joe. He is only four years old, but he has already mastered the art of exaggeration. If he has a sip of super milky coffee, because he wants to be just like his uncle, he will claim it is 'the best, most delicious drink he has ever tasted. Ever. In the history of hot drinks.' He has mastered hyperbole without even knowing what it is.

Don't be afraid to exaggerate and be bold and go big with your dialogue. Conversations between children are always larger than life, so remember this when you're speaking for your characters.

Get your copy of The Unexpected Tale of Bastien Bonlivre now

Clare Povey is the author of The Unexpected Tale of Bastien Bonlivre, a middle grade mystery adventure set in 1920's Paris. Clare grew up on the border of where East London meets Essex. After studying French and living in Northern France to teach English in primary schools, she joined the Writers & Artists team at Bloomsbury Publishing to grow their writing and publishing events and is now Editorial & Communities Manager at W&A.

Comments