Writer Cecilia Ekbäck discusses the importance of place in Scandinavian literature and how this has influenced her debut novel, Wolf Winter.

Just before Christmas, I was asked to write an article for Strand Magazine in the US.

"Write about Scandinavian crime novels," they asked.

"What is it about Nordic Noir that is so special?"

I pondered. What seems "special" to me about Scandinavian literature is how authors use ’place’ in their writing: place—in the broadest sense of the word – geographical, social, religious. The location where the scene is laid—the architect of the experience in the mind of the reader—is allowed to become more than simply a supporting element in much of our fiction. As for geographical setting, there is the contrasting imagery of a small, picturesque town ravaged by murder, as in the novels by Camilla Läckberg, or the quite remarkable urban scene in the Stockholm Noir trilogy by Jens Lapidus. The snow in Peter Høeg’s Smilla’s Sense of Snow not only helps Smilla to solve the crime, but provides for poetic descriptions of a foreign and exotic landscape. Swedish crime writing has often contained a strong societal setting. We see it as early as the 1960s and ’70s in the ground breaking series about policeman Martin Beck, written by Maj Sjöwall and Per Wahlöö, later in Henning Mankell’s books about Wallander and, lately, in Stieg Larsson’s Millennium Trilogy. The crimes to be solved demonstrate blatantly and shockingly the failure of the system, and the heroes come to realize its shortcomings. The rich folklore is explored by Swedish Johan Theorin and Icelandic author Yrsa Sigurdardóttir, who successfully mix mystery with spooky ghost stories. For the most part, the characters, the plot, and the setting are so tightly bound together that they seem inseparable. Perhaps because this is the way things actually are for us: place is indelibly etched upon our consciousness, and upon our lives.

My grandmother used to say:

"I don’t think I’m living in Lapland as much as Lapland is living in me."

Growing up in northern Sweden has made its mark on me. The long winters, the six months of darkness, and the seemingly endless forest landscape are in sharp contrast to the summer midnight sun, the hot weather, and the absolute explosion of flora and fauna. One season is lived as quietly as the other is experienced exuberantly. To a large part, this setting governs the rhythm of our lives and imprints itself on our psyches.

And the ’noir’ in Nordic Noir? Perhaps it is because we know our days of sunlight are numbered? There is a Swedish word, vemod, that has no direct English translation but means a sort of bittersweet melancholy, a longing. I believe that vemod is a typical national trait. This "missing" feeling dampens me and makes me ache, but it is also what drives me. I don’t think I would want to be without it.

I, too, am interested in ’place’ and its capability to influence us. I like to contrast it with heritage – what is just there in us, inherited from generations and generations. The arrival of our twin daughters changed my view on nurture versus nature. I used to be heavily weighted towards the former, but each girl arrived with her own personality from day one. This ‘inheritance’ doesn’t absolve us from responsibility and, of course, all our actions have consequences, but the thought gives me some comfort.

Blackåsen Mountain is the embodiment of what I felt like growing up in the north of Sweden. It represents the fear, the doubts, the religious fervour, the loneliness and the need to fit in and to belong.

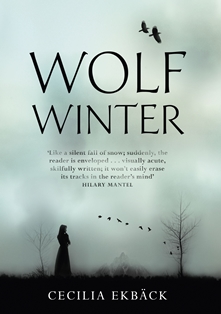

In WOLF WINTER, I tried for 'place', or Blackåsen Mountain, to be almost a character in its own right. It watches the settlers. It doesn't care. It is dispassionate. It has already seen many of them come and go and it will see many more come and go.

In the interludes, it felt right to, give this 'place' a voice. In the olden days when there were no roads in Lapland, there were these periods when the snow did not carry the weight of a man, either because it had just fallen or because it was melting, and the settlers were confined to their homesteads for a few weeks. I liked the idea, because it forces a solitude onto the character in which they cannot take any action, but can only reflect on what has happened and worry about what is to come. Ultimately, before the elements, they are powerless.

Born in Sweden, Cecilia Ekbäck, who received an MA in Creative Writing from Royal Holloway, has returned to the landscape and history of her childhood to bring Wolf Winter to vivid life. She speaks Swedish, English, French and Russian fluently and has some Spanish, Portuguese and German. Cecilia now lives in Calgary with her husband and twin daughters and is at work on her second novel. Visit her website for more information. Wolf Winter (Hodder, £14.99) is out now.

Comments