Author Katie Mitchelson discusses how she structured her book, Wrecked, in a format inspired by her PhD research.

My novel Wrecked, which I wrote in partial fulfilment of my PhD, primarily explores how trauma and adverse childhood experiences can leave young people susceptible to criminal exploitation, but it is also an exploration of how stream of consciousness can be presented in Young Adult (YA) fiction.

My interest in the various ways diverse experiences and individual narratives can be presented in fiction, ultimately influenced my decision to undertake a PhD, to explore through research and practice how I might develop my own unique representation of consciousness, while developing a better understanding of how literature reflects and shapes our world. Although a PhD is not essential to becoming a better writer, for me it provided the space to conduct the research I needed to fully understand stream of consciousness.

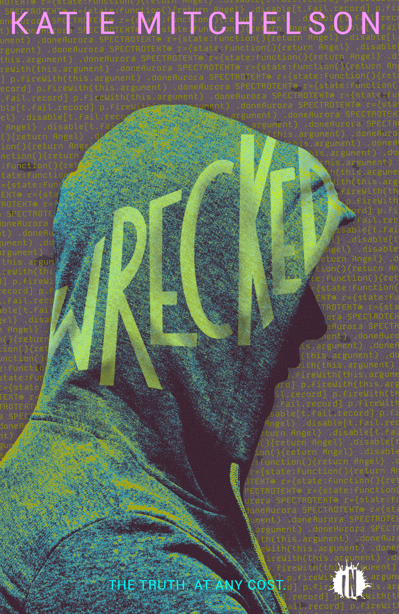

My approach to stream of consciousness in Wrecked is framed within a series of records from a fictional technology called ‘Spectrotext’, which was influenced by neuroscientific studies of consciousness, and emerging technologies, such as Elon Musk’s Neuralink (An Integrated Brain-Machine Interface Platform with Thousands of Channels, 2019).

The novel is structured as though the young protagonists have gathered their Spectrotext records and reflections on events, giving access to deeply personal moments of interiority. I wanted to place the reader directly inside the heads of the protagonists, and demonstrate a fragmented, fractured consciousness that is the result of exposure to trauma, danger and adversity.

I was concerned that immediately immersing my younger readers into my protagonists’ stream of consciousness could be off-putting, as it is an uncommon technique in YA fiction, but I felt that capturing them as moments that the Spectrotext implant has recorded and downloaded to a mobile phone app, may make the format more accessible to a YA audience. My research across critical theory, also led me to believe that the fictional Spectrotext, leant towards the tropes of Dystopian fiction, which is popular with YA readers. It helped me to develop an alternative reality, a story-world that considers the ethical implications of emerging technologies, whilst exploring important social issues affecting today’s youth.

Although Spectrotext felt like a fun and exciting way to present stream of consciousness, the style of writing itself was not without its challenges.

I conducted a lot of research across the fields of psychology, consciousness and creative writing, and I initially used the process of free association, which has its roots in psychology, and refers to sharing seemingly random thoughts and memories that pass through the mind. The principle involved in this technique is that a word, an idea or an image can act as a stimulus to a series or a sequence of other words, ideas, or images, which are not necessarily connected in a logical relationship. For the author, it allows the freedom to present the association of thoughts and memories of characters, which might be stimulated by observations, such as remembering certain memories. In experimenting with this principle, I used particular memories from the protagonists’ past that were relevant to the moment that they were experiencing. I then imagined specific images related to these memories, and attached words to describe the image, which I then threaded together.

In demonstrating each protagonist’s subjective experience, I considered elements of Crick and Koch’s A Framework of Consciousness (2003), which details ten stages of conscious experience, to see if I could use their theories to develop stream of consciousness further. For example, I considered how I might use ‘Snapshot’, which is the representation of conscious awareness as a series of static snapshots (2003) to consider how my characters’ experience time; Zombie Modes, which are unconscious actions that happen because of sensory input, to consider how my characters might think about movement (2003); and also Attention Neural Activity, which explores how details from visual imagery are assimilated, with the individual being aware of only basic details initially (2003), to consider how my characters might recall memories. To represent this principal for example, I used minimal description of the action in the present, but the associated memory is much richer in detail, a myriad of feelings, thoughts and images that are relevant to what is happening in the present.

A further challenge was ensuring that the timeline remained correct. I had captured various characters’ interiority, and those had to align to create a seamless series of events, ensuring I could build suspense for my readers. I had to keep a track of which characters knew what, particularly as the story has a twist that is revealed late in the novel. I had prepared for this, by plotting the main sequence of events, and, in my practice with free association, I created diary entries from the perspective of each of my characters, with each of them telling their own version of events. Each of the Spectrotext entries are also date stamped, which helped me when constructing the novel, but which I also believed would help the reader keep track as the story develops.

I feel that using stream of consciousness was a powerful way to explore the interiority of my characters as they navigate the disturbing events of the story, whilst also contributing the practice and study of presenting consciousness in fiction. Combining stream of consciousness with emerging technology may also prove to be good way to make experimental fiction more accessible to a mainstream YA audience.

Katie Mitchelson has worked as a youth worker in the North-East, which inspired the town of Waterfell in Wrecked. Her work with young people inspired a lot of her writing during her creative writing PhD, compelling her to write about teenagers who do not realise that they are victims, who do not realise that they are being groomed for criminality, and the wider problems of country lines.

References

Crick, F & Koch, C (2003) A Framework of Consciousness. Nature Neuroscience. 6. P. 119-26. Available from:

Musk, E (2019) “Neuralink: An Integrated Brain-Machine Interface Platform with Thousands of Channels”. Journal of Medical Internet Research. Oct 31; 21(10). Available from: https://doi: 10.2196/16194

Comments